August has come again — the time when astronomy enthusiasts travel to areas with an open horizon and a dark sky for night observations. The main event of this month usually becomes the Perseid meteor shower, which is considered the third most powerful of the visible Northern Hemisphere. But in recent years, even at the maximum, the number of meteors of this stream is getting smaller. Why is this happening and how long will this fall last?

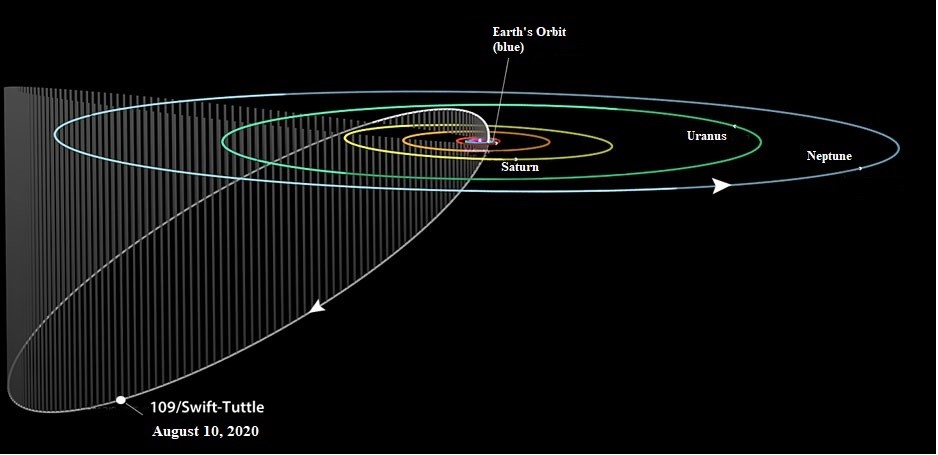

Perseids have been observed since the Middle Ages — Catholics know them as the “tears of St. Lawrence”, whose name day falls on August 10. As a separate meteor shower with a radiant in the constellation Perseus, they were allocated in 1836, and in 1866 they were “associated” with the periodic comet Swift-Tuttle (109P/Swift-Tuttle), discovered four years earlier. The passage of this comet near the Sun and the Earth helped to activate the flow and attract attention to it. But soon it was “eclipsed” by powerful meteor showers, which gave the inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere the November Leonids and Andromedids.

The rains have passed, the Perseids have remained. They consistently “produced” a maximum of 50-60 meteors per hour, decorating the August sky and reminding of their “parent” comet. Astronomers did not know when it would return — observations made visually in the XIX century did not allow calculating its orbit with acceptable accuracy. Previously, its period was estimated at 118 years, which meant a return in 1980. The comet did not appear that year, but the associated flow showed a noticeable increase. Some observers reported an anti-aircraft hourly number of more than 300. But later again there was a noticeable decline almost to the “standard” values.

Brian Marsden, a specialist in small bodies of the Solar System, once again carefully reviewed the archival data, where he managed to find information about Kegler’s comet, observed in 1737. Its path through the sky did not “fit” well into the orbit of comet Swift-Tuttle. Taking into account these observations, the next passage of its perihelion (the closest point of the orbit to the Sun) was to take place in November-December 1992. This time the prediction came true — the “tailed star” was rediscovered by the Japanese Tsuruhiko Kiyuchi on September 26 of the same year. But even before that, on the night of August 12-13, astronomers noted another surge in Perseid activity.

After the impressive “sky show” of 1993, when observers of Western Europe and the east coast of North America registered more than half a thousand meteors per hour at the maximum of the flow, Perseid activity began to decline naturally. The reason for this is not difficult to understand if we recall that the Swift-Tuttle comet should be considered “young” — only it is necessary to measure the time of its stay on the current trajectory not in Earth years, but in units of the duration of its complete revolution around the Sun. The dust particles ejected from its core during its flights through the central regions of the Solar System did not have time to spread evenly enough along the comet orbit and form a kind of near-nuclear condensation. Two more “dust clouds” of increased density are moving ahead and behind it at a distance that corresponds to 12 years. Their appearance is most likely caused by the influence of Jupiter’s gravity.

Near other parts of the comet’s orbit, the concentration of dust particles is much lower, so the activity of the Perseids at the maximum will remain at the level of 50-60 meteors per hour for a long time. It may even decrease slightly by 2059, when 109P/Swift-Tuttle will pass aphelion — the farthest point from the Sun. Then their activity will gradually increase, and the first relatively powerful peak should be expected as early as 2114.

This year, during the Perseid maximum, the Moon will just enter the full moon phase, and therefore, it will greatly interfere with observations. But if there is a clear sky, astronomers will still observe this flow. Small bodies of the Solar System, which include comets and meteors, are able to surprise us from time to time, and it is very desirable to track and document each such surprise. The help of astronomy enthusiasts in such cases is often very useful.

Follow us on Twitter to get the most interesting space news in time

https://twitter.com/ust_magazine