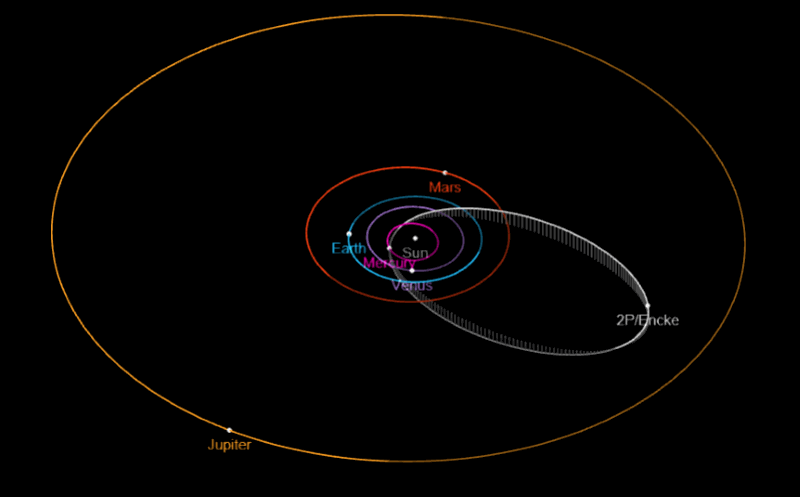

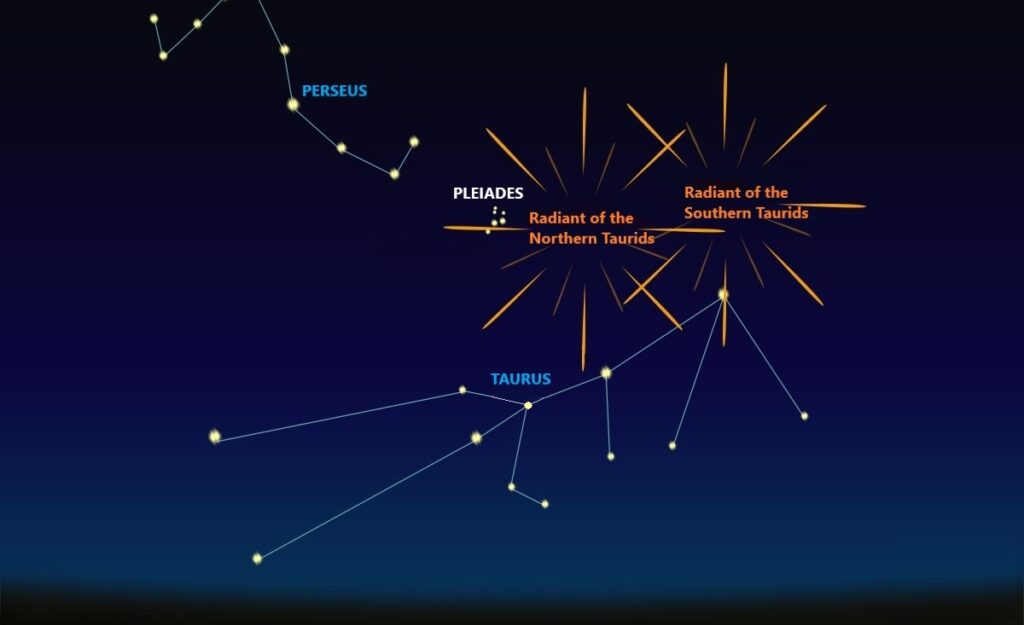

The beginning of November is marked by two fairly active meteor showers — Southern and Northern Taurids. The first one is slightly weaker and has a peak of activity at the beginning of the month. The activity of the second is noticeably higher and at the maximum, falling on November 11-12, can reach 20 meteors per hour. Both of these showers are associated with comet Encke (2P/Encke), which has the shortest orbital period of all known “tailed stars”: it returns to the Sun every 3 years and 4 months.

This famous “tailed star” in the catalogs of short-period comets has the number 2. Its discoverer is the Frenchman Pierre Menschen, who noticed it on January 17, 1786. But, like the “first number” of the comet catalog, named after the outstanding English scientist Edmund Halley, it was named not by the one who first saw it, but by the one who calculated its orbit and proved its periodicity. This was done in 1819 by the German astronomer Johann Franz Encke. It was somewhat easier for him than for his predecessor — at the beginning of the XIX century, the accuracy of observations increased significantly and more advanced methods of processing them appeared. All appearances of comet Encke since 1818 have been successfully observed, except for 1944, when the Second World War intervened in astronomical research.

The orbit of comet Encke comes closest to the Earth’s orbit at a distance of 0.173 AU (25.8 million km). This is quite a lot; nevertheless, on June 12-13 — the days when our planet passes the point of maximum convergence — the maximum of the most powerful daily meteor shower is observed Zeta Perseids, and the trajectories of its meteors are very similar to the cometary orbit.

The fact is that this orbit is gradually changing under the influence of the gravitational force of large planets. Once it lay closer to the earth’s orbit, and many dust particles ejected by the comet hundreds of years ago are still moving along the “old path”, having the opportunity to collide with the Earth. The same gravitational influence, as well as the pressure of sunlight and other factors cause the meteor swarm to slowly disperse in space, while its cross-section increases, and the number of particles per unit volume, on the contrary, decreases. Therefore, a noticeable number of meteors associated with comet Encke is observed not only in mid-June, but also in November, when the minimum possible distance to it is even greater. But at this time, meteor particles hit the Earth from the night side, and we can easily see them.

The history of the northern “branch” of the Taurid swarm is even more interesting. Since it is significantly more powerful than the southern one, it could be expected that it arose later, since it has not yet had time to dissipate. But this contradicts the data on the evolution of the comet’s orbit. The contradiction was resolved in 2004, when a small asteroid was discovered a little less than a kilometer in size, which received the designation 2004 TG10. Calculations of its trajectory indicate that it is probably a fragment of the nucleus of comet Encke, separated from it several thousand years ago. Gradually their paths diverged, the asteroid’s orbit changed more slowly (it has a slightly longer period of orbit the Sun), in our era its minimum possible distance to Earth is only 0.0225 AU (3.37 million km), so we annually pass through a fairly dense part of the swarm associated with it. Almost certainly in the distant past, 2004, TG10 also looked like a comet, formed a coma, tail and “scattered” meteors. Now in memory of its “cometary past” there is a shower of Northern Taurids. Someday, comet Encke, which could be seen with the naked eye back in 1980, would completely exhaust the reserves of volatile substances in its core and turn into an ordinary “dead” near-Earth asteroid. Our not very distant descendants will be able to observe it only with powerful telescopes.

Like the Southern Taurids, the Northern ones have their daily “equivalent” — a fairly powerful stream of β-Taurid, the maximum of which falls on June 29. Some astronomers believe that a large body that entered the earth’s atmosphere on June 30, 1908, and later received the name “Tunguska event” belonged to it. According to the available data, it also moved from the direction of the Sun, and its relative speed did not exceed 30 km/s (for the β-Taurid and ζ-Perseid meteors, it is 29 km/s).

Unfortunately, climatic conditions in Ukraine do not allow for full-fledged annual observations of Taurids – November in our latitudes is usually cloudy. In addition, this year the sky on the night of the maximum will be strongly illuminated by an almost full Moon. And in general, Leonids are much more “popular” from meteor showers, the peaks of activity of which fall at the end of autumn. Every 32-33 years they decorate our sky with real meteor showers with a capacity of several thousand or even tens of thousands of “falling stars” per hour… but that’s another story.

Follow us on Twitter to get the most interesting space news in time

https://twitter.com/ust_magazine