On February 1, 2003, the space shuttle Columbia was returning to Earth after 15 days in space. Less than 20 minutes remained before the planned landing on the runway of the Kennedy Space Center. None of the astronauts anticipated they were doomed.

At some point, the Mission Control Center (MCC) lost contact with the ship. At first, experts hoped it was some technical failure, but soon it became clear that something irreparable had happened. Observers who followed the descent of the shuttle reported that it broke into many fragments. After a while, a loud explosion sounded on the ground and then debris began to fall from the sky. 17 years after the Challenger disaster, NASA has lost another spacecraft and its entire crew.

Pioneer ship

Columbia deservedly received the status of a pioneer. It was the first specimen of the Space Shuttle craft intended for space flights. Its construction began in 1975, it was handed over to NASA in 1979, and two years later it finally went into orbit around the Earth. This flight went down in history as the first mission of the shuttle and as the first time when the orbital test of a new spacecraft was conducted not in unmanned mode, but with a crew. Despite the increased risk, the experiment was a success, paving the way for further development of the program.

Since Columbia was the first ship of the series, it was different from all subsequent “shuttles”. In particular, various experimental equipment was installed on board. In addition, it weighed more than other shuttles. Also, the ship did not have its own docking system, which meant its inability to dock with the orbital station. Therefore, Columbia participated neither in the Mir-Shuttle program nor in the construction and supply of the ISS. The ship was used only for certain missions, which involved putting satellites into orbit, conducting experiments and scientific research, and servicing the Hubble telescope.

However, the situation might change in the future. NASA planned to modernize the shuttle Columbia equipping it with a docking system that would allow it to join the ISS program. The first such mission was planned for the end of 2003…

Challenger: conclusions not drawn

In 1986, the reusable ship program experienced a serious blow that almost became fatal for it. The crash of the Challenger shuttle triggered a series of events that affected almost all areas of the American space industry. The most obvious consequence of the disaster was the revision of safety standards and the introduction of changes in the design of winged ships to make their operation safer.

Unfortunately, no improvements could change the main thing: this ship was a very complex system consisting of thousands of different components. The failure of many of them could have caused a disaster. At the same time, the shuttles never had a full-fledged crew rescue system in case of an accident. In addition, despite all efforts to improve the organizational structure and culture of decision-making at NASA, many rules and regulations have not taken root. All this constituted a fertile soil for new disasters. The only question was when it would happen.

The first truly dangerous incident occurred in 1988 during the second flight after the crash of the Challenger spacecraft. A piece broke off from a side booster crashing into the heat shield of the shuttle Atlantis. The incident was recorded by ground cameras. After entering orbit, the crew inspected the impact site and found a broken tile. But, despite the report of damage, the MCC did not take it seriously, assuming the astronauts to be misled by the play of light and shadow.

The ship was lucky enough to land safe. It was later discovered that the damage was indeed there, but an additional aluminum plate was found under the broken tile, and this saved Atlantis. Unfortunately, NASA has not made any long-term conclusions or developed control procedures in case a similar situation occurs again.

Another incident occurred in 1999 during the STS-93 mission. Then, while launching the shuttle Columbia, two of the three engine control units failed. The ship was saved by the backup controllers — if it weren’t for them, it would have to splash down.

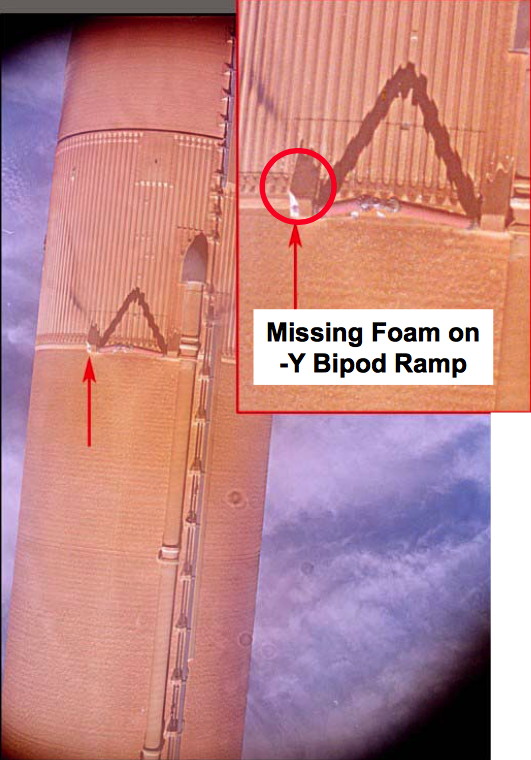

Four years later, Columbia was again preparing for space flight. The purpose of the STS-107 mission was to conduct a series of scientific experiments. After numerous postponements, the launch was scheduled for January 16, 2003. The ship broke away from the launch pad and began to gain altitude. At the 82nd second of flight a piece of insulating foam, intended to prevent the formation of ice, separated from the left fairing of the shuttle’s attachment to the fuel tank. At that time, Columbia was at an altitude of 20 km, moving at a speed of 3013 km/h. A fragment, as big as a suitcase, struck the edge of the shuttle’s left wing and fatally damaged it.

Normalization of deviance

NASA specialists watching the launch broadcast did not notice the impact. But while studying the video recording of the launch the next day, the engineers realized that there was a hit. And then something happened, for which the term “normalization of deviance” had been coined by the investigators of the Challenger crash.

The thing is that this was not the first time when pieces of foam broke off from the fuel tank and hit the ship. Such incidents happened at least four times. And one of them happened during mission STS-112 — just three months before Columbia’s last flight. Ironically, a special camera was installed on the fuel tank of the shuttle for the first time, intended to monitor the state of its thermal insulation coating. Thanks to this, specialists managed to determine the characteristics of the detached fragment and the place of its impact. A piece of foam measuring approximately 100×125×300 mm entered the connecting ring at the point of attachment of the left solid fuel booster to the fuel tank. Further inspection revealed that the impact had left a 100 mm wide and 76 mm deep dent in the metal.

The STS-112 incident caused no in-flight problems. So, as in other similar cases, the management of NASA deemed it better to turn a blind eye to the problem, guided by the already mentioned principle of “normalization of deviance”: if previously everything had gone well, then the system has a sufficient resource of reliability and there is nothing to worry about.

However, not all employees of the organization shared the position of the management. The impact of the foam on the wing of the Columbia worried many experts. They tried several times to send a request to the US Department of Defense with a request to use military satellites to search for signs of possible damage. It is good that the Pentagon already had the experience of such an operation. During Columbia’s first test flight in 1981, reconnaissance vehicles photographed the heat shield, confirming that the craft was not damaged during launch. And if senior NASA officials had endorsed the request, the military would likely have provided support again.

But this did not happen. The leadership of the aerospace administration not only refused to help, but actually opposed such an initiative. The risk assessment became a stumbling block. A special software tool was at the disposal of NASA specialists, designed to simulate the impact of small fragments on the heat-protective coating of shuttles. The first problem was that it was mainly used to assess the damage that ice chunks could cause, while insulating foam had other characteristics.

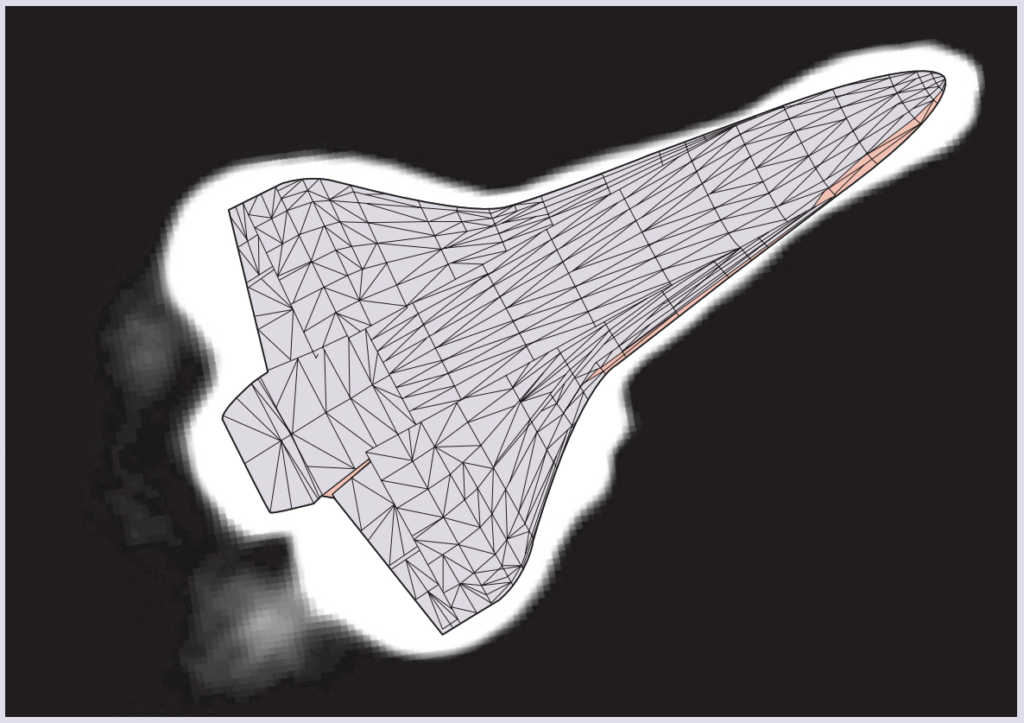

Another problem was the lack of information about the exact location of the impact. The fact is that heat protection from different materials was used on the shuttle body. Most of the ship was covered with silicate tiles. However, the nose of the fuselage and the leading edges of the wings, which were the most heated during entry into the atmosphere, were protected by panels of reinforced carbon plastic, which was a multi-layered structure of carbon fabric impregnated with phenolic resin.

When assessing risks, experts were forced to make a number of assumptions. But during the analysis, they came to the alarming conclusion: if the impact had landed on the carbon fiber panel, there is at least a 6 percent chance that the foam would have pierced it.

But because of the same conventions and assumptions, the flight controllers decided that the engineers were giving too much importance to the incident, overestimating the danger. After all, the thermal insulation foam had a very low density and was practically weightless. Even with the significant speed of the collision, it was hard to believe that it could have caused serious damage. So, on the one hand, the higher ranks of the aerospace administration were convinced that such a scenario was very unlikely, and on the other hand, the engineers failed to stand up for their point of view and preferred to agree with the management. Therefore, NASA never sent a request to the Pentagon.

Not only technical factors could play a role in the assessment of the situation, but also the widespread opinion among specialists that even if the shuttle is damaged during the launch, there is nothing you can do about it and it is easier not to know about it.

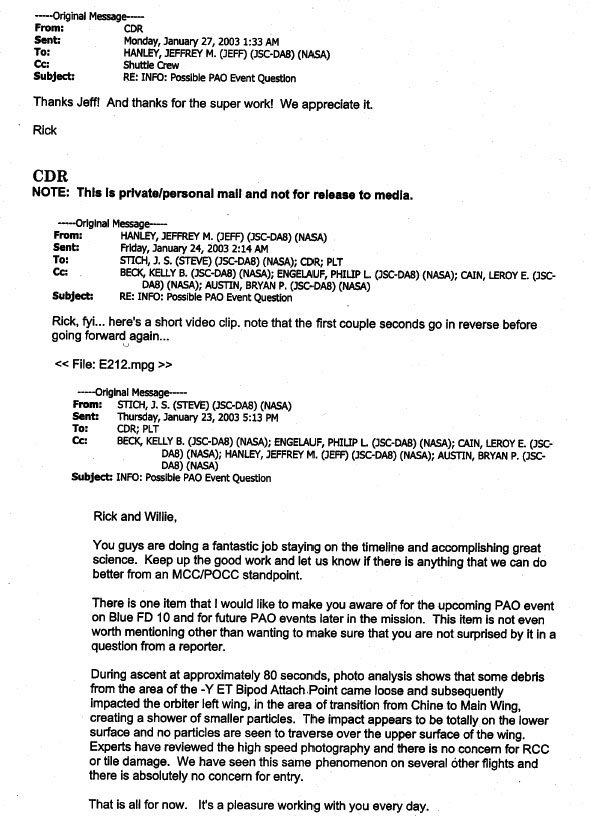

It is worth noting that the crew of the Columbia spacecraft was informed about the incident, but on January 23, the astronauts received an e-mail from the flight director with the following content: “Experts have reviewed the high-speed photography and there is no concern for RCC of the damage. We have seen the same phenomenon on several other flights and there is absolutely no concern for entry.”

What if?

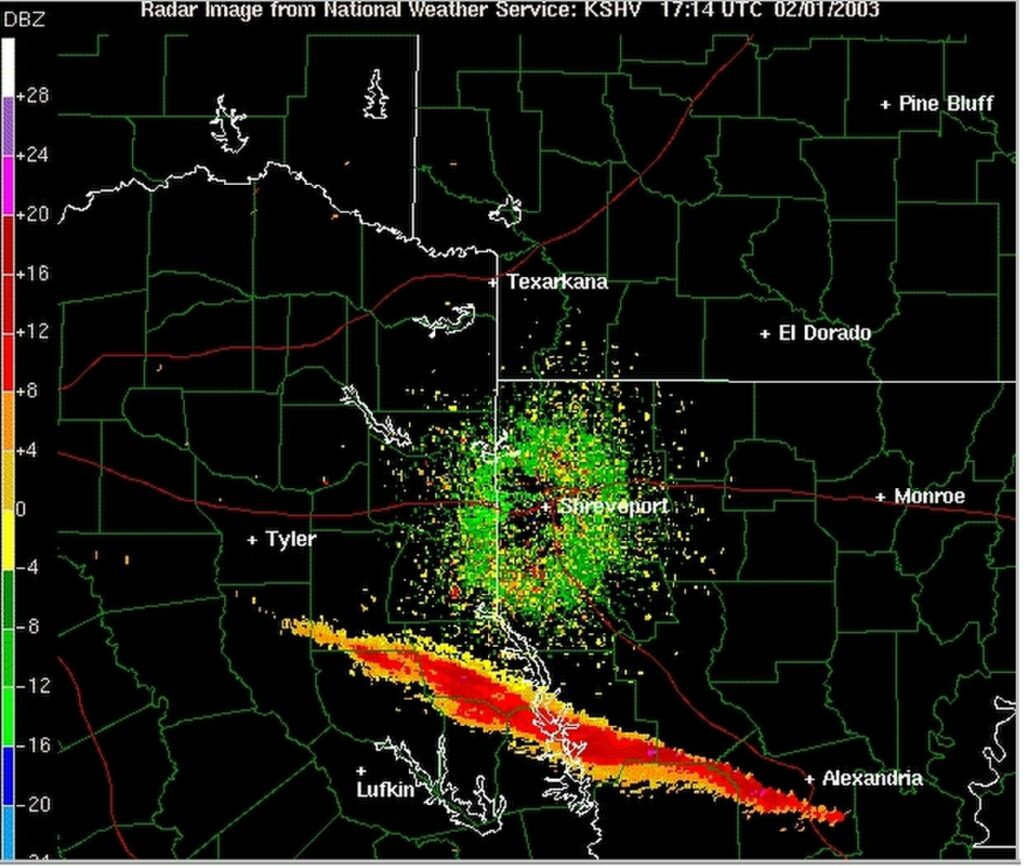

We all know what happened next. During entry, hot gases penetrated the hole in the left edge of the ship’s wing and began to gradually destroy it. Eventually, they burned out the hydraulics, and the Columbia lost control, spinning erratically, before breaking into many pieces. Seven astronauts are believed to have died within a minute of losing contact with the MCC. In the weeks that followed, search teams discovered tens of thousands of pieces of debris. The only survivors of the disaster were the nematode worms. They were in a sealed container found among the fragments of the shuttle.

But did the crew of STS-107 really have no chance and the astronauts were “lucky” to die a sudden death? And would detecting the damage by the satellite imaging process early in the flight make any difference?

Since this was a stand-alone mission, Columbia could not reach the ISS and use it as a shelter — the shuttle was in an orbit of different inclination and did not have enough fuel to perform the necessary maneuver. But there were other options. For example, the crew could go into outer space and try to repair the damage with improvised means (say, using metal plates from the cockpit). Of course, the astronauts were not prepared for such a risky operation. However, the ship was equipped with a Canadarm manipulator arm (a device not needed for STS-107 mission) that could have transport repairmen immediately to the damaged area. Of course, even if the crew tried to repair the wing, the effectiveness of these actions is almost impossible to predict. But still, it was a chance for salvation.

A more realistic possibility was the organization of a rescue expedition using another shuttle. In a normal situation, NASA had no such option. At maximum resource savings, Columbia could remain in orbit for 30 days (until February 15, 2003). This was not enough time to prepare a rescue craft from scratch, so the STS-107 crew would have had to choose between death by suffocation and death on reentry.

Coincidentally, at that time, NASA engineers were already hard at work preparing another mission involving the shuttle Atlantis and had already managed to complete a significant part of the necessary work. The launch was scheduled for March 1, but later calculations showed that with the maximum acceleration of the procedures, the shuttle would be able to go into space on February 10. Thus, rescuers would have five days left to approach the doomed ship and evacuate the STS-107 crew.

After rendezvous, the rescue team would enter aboard Columbia to deliver lithium hydroxide capsules (to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide aboard the damaged craft) and additional spacesuits. They also would connect two shuttles with a sliding pole to facilitate the passage procedure. After that, the STS-107 crew would gradually move to Atlantis and use it to return to Earth. As for the disabled shuttle, it would be put into remote control mode and de-orbited over the Pacific Ocean.

Undoubtedly, this mission would go down in history as the most difficult and daring rescue operation of all times and nations. Almost certainly, its name would have become well known, everyone involved would have received awards, written memoirs that would later be filmed… But, unfortunately, history does not know the subjunctive mood.

Consequences of the disaster

Like the Challenger disaster, Columbia’s wreck had a number of long-term consequences. The most obvious of them was a long discontinuance in the flights of shuttles, which led to the suspension of the construction of the ISS. The next mission involving the winged craft took place as late as July 2005.

Of course, NASA has again reviewed the safety standards. In particular, the aerospace administration decided to completely abandon all manned missions not related to the construction of the ISS. This was grounded on the fact that in the event of a repeat of the situation with damage to the thermal protection, the crew would be able to use the orbital outpost as a shelter. Also, a mandatory item was added to all flight schedules: after flying to the ISS, the ship stopped at a certain distance from it and made a 360° turn, which allowed the station crew to check the state of its thermal protection.

It was only because of very strong pressure from the scientific community that NASA eventually authorized an “exceptional mission” — a final Hubble maintenance expedition using the space shuttle Atlantis. At the same time, the organization took increased precautions: during the launch, the shuttle Endeavor was on the nearby launch pad. In case of damage to the thermal protection of the first ship, it would be involved for a rescue expedition.

But the main consequence of the disaster was the adoption in 2004 by President George Bush of a fundamental decision to abandon reusable ships. After the completion of the ISS construction, the shuttles were retired. They were to be replaced by the new manned Constellation program, the declared goals of which were flights to Earth orbit, the Moon and Mars.

However, Constellation did not manage to “take off”. The large scope of the project, multiplied by the reluctance of Congress to allocate the necessary funds for its financing, led to the fact that it, in fact, did not even start on. As a result, in 2010, the administration of Barack Obama closed the program. At that time, the shuttles’ dismissal was less than a year away, and the US still had no other spacecraft.

After some thought, it was decided to change the approach and bet on the private sector. While NASA continued to work on creating a manned system for interplanetary missions, private companies began to deliver astronauts to the ISS. During the break between the end of the shuttle flights and the launch of commercial ships, the only way for Americans to get to the station was to buy seats on the Russian Soyuz. Altogether, this break stretched for nine long years.

As for the shuttles, Atlantis made its final landing at Cape Canaveral on July 21, 2011, ending the program’s 30-year history. Soon all the winged ships were sent to museums. The atmospheric prototype Enterprise was placed in the Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York, Discovery settled in the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, the shuttle Endeavor took up permanent parking at the California Science Center in Los Angeles, and Atlantis is now exhibited at the Kennedy Space Center.