On 29 March 1974, humanity first got an idea of what exactly Mercury looks like. That day, half a century ago, the Mariner 10 spacecraft made a historic flyby of the planet which is the closest to the Sun.

Secrets of the first planet

For most of history, humanity knew virtually nothing about Mercury. And even by the beginning of the space age, the situation had not changed much. Consider just one simple example. For a long time, scientists believed that Mercury was constantly facing the Sun with the same side and that there was no change of day and night. It was only in the early 1960s that radar data revealed that this was not the case. In fact, the planet makes one revolution around its axis in 58 Earth days, while the period of its rotation around the Sun is 88 days.

What exactly the surface of the planet looks like was also a matter of conjecture. Of course, astronomers used telescopes to try to map Mercury, but their accuracy left much to be desired. The only way to reveal the secrets of the planet was to launch an automatic device to it. And in the early 1970s, NASA addressed this problem.

Gravity to the rescue

Sending a spacecraft to Mercury is not so easy. In addition to the need to protect it from high temperatures, it is also necessary to find a way to cope with the Sun’s gravity. It will “pull” the spacecraft towards itself, which makes it extremely difficult to enter orbit around Mercury.

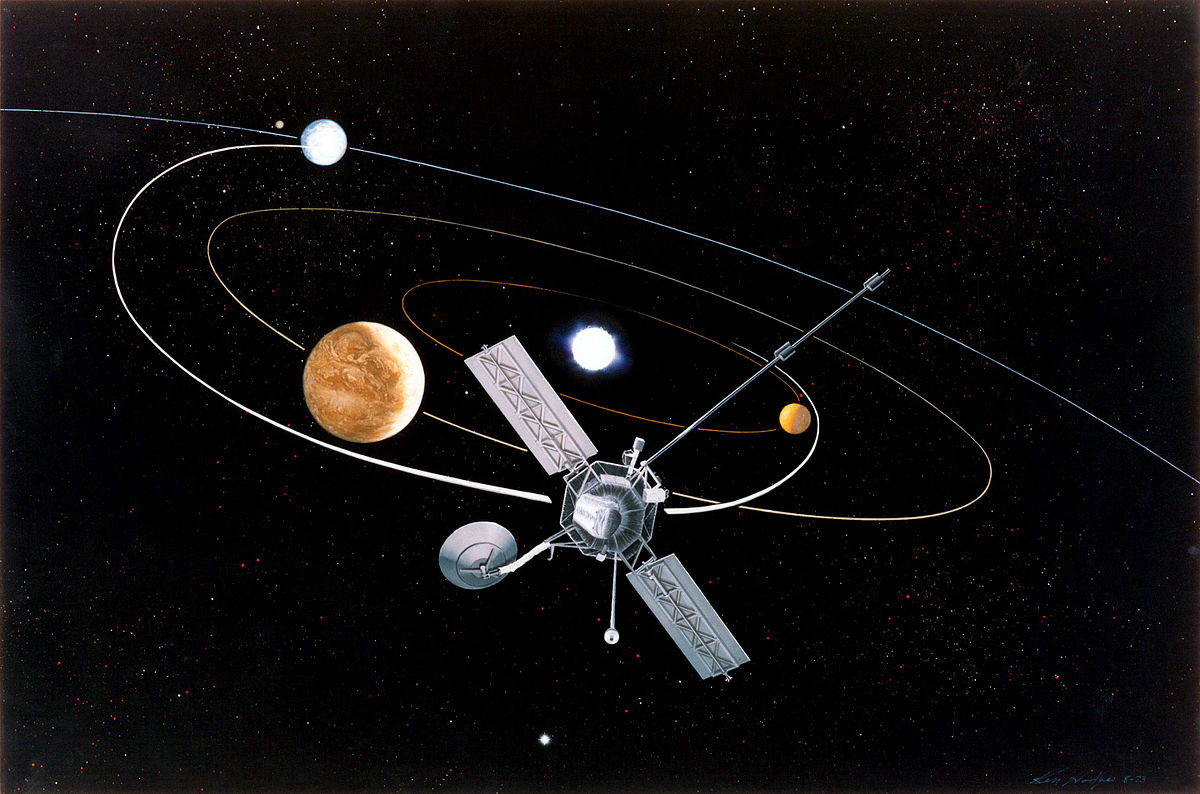

The gravity manoeuvre as imagined by an artist. Source: NASA

The first solution is to equip the vehicle with huge reserves of fuel, which requires launching it with a super-heavy carrier such as the Saturn V. The huge price automatically puts an end to the concept of such a mission.

The second option is to use a series of gravity manoeuvres to gradually slow down the vehicle. The advantage is that a less powerful rocket can then be used. However, there is also a significant disadvantage in that the flight will take many years. Nowadays, this is no longer a problem, but in the early 1970s, the reliability of space technology did not yet allow for a mission of this duration.

Mariner 10 as imagined by an artist. Source: National Air and Space Museum

Therefore, NASA chose a different path and decided to send a spacecraft to Mercury to study it from a flyby. It was named Mariner 10.

Technical design of Mariner 10

Mariner 10 was built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Its weight was 500 kg. The spacecraft was equipped with a television camera, an infrared spectrometer, a radiometer, plasma and charged particle instruments, and a magnetometer.

The Mariner 10 backup spacecraft on display at the museum. Source: National Air and Space Museum

To get to Mercury, NASA engineers developed a flight plan that included a flyby of Venus to use its gravity for additional acceleration. Thus, Mariner 10 was to become the first spacecraft in history to visit two planets at once.

A visit to Venus

Mariner 10 was launched on 3 November 1973. Its first targets were the Earth and the Moon. The mission specialists used them to check the correct operation of the probe’s instruments and to practice.

Earth and Moon in Mariner 10 images. Source: NASA

The images taken by Mariner 10 were not only of practical but also scientific value. It managed to obtain the first high-quality images of the Moon’s north pole, which made it possible to update lunar maps and find a number of previously unknown craters.

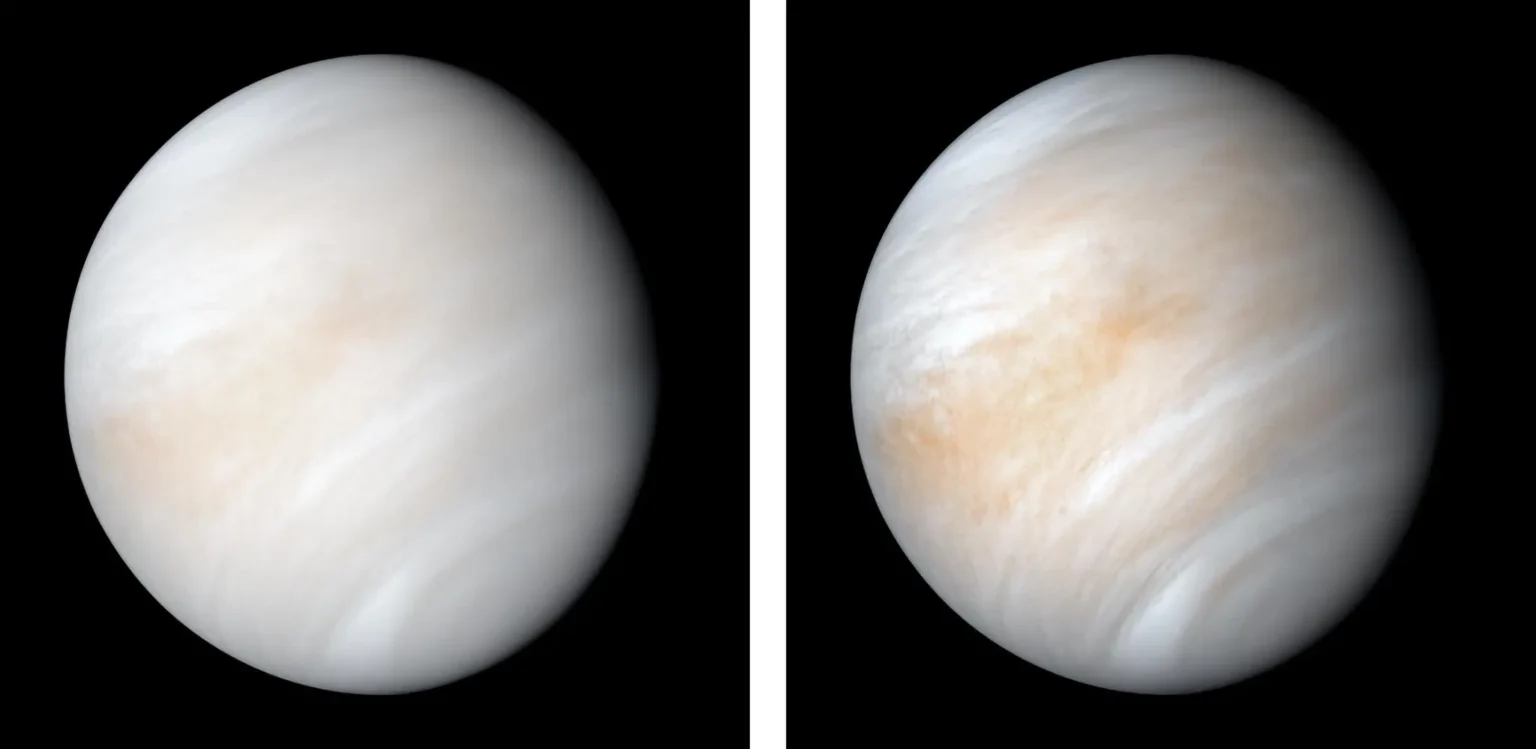

A photo of Venus as seen by the human eye (left) and a photo with enhanced colours (right). Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

On 5 February 1974, Mariner 10 flew by Venus and took the first-ever picture of it from space. By that time, a number of spacecraft had already visited the planet. But before Mariner 10, no one had ever taken pictures of it. This is because the surface of Venus is constantly hidden by a thick layer of clouds. Therefore, the designers of the Venusian missions did not equip them with cameras, believing that the scientific return on such images would be too scarce.

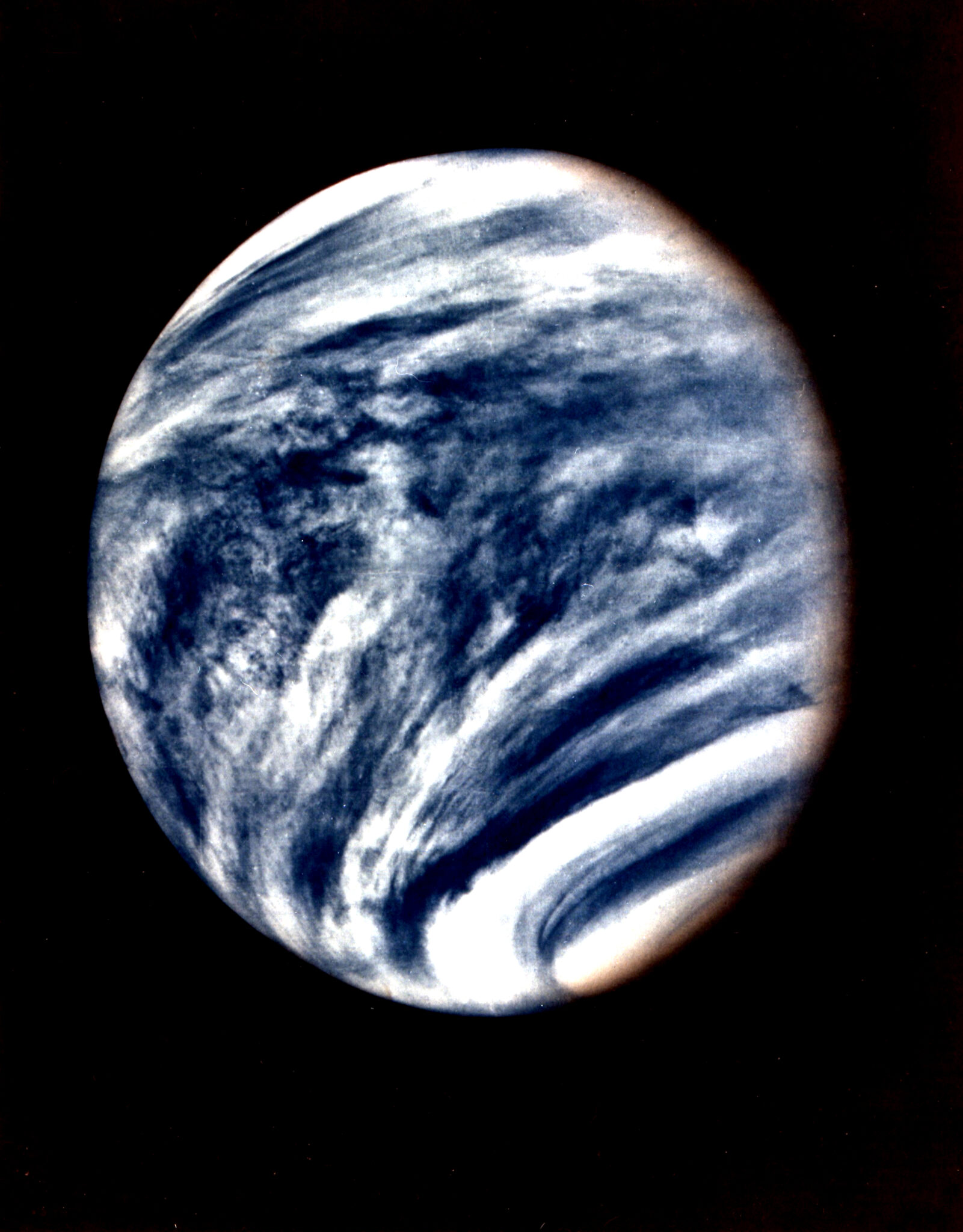

Venus’ clouds in the ultraviolet range. Photo by Mariner 10. Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Mariner 10 has shown that such perceptions were wrong. While Venus was indeed unremarkable in visible light, the ultraviolet images revealed many previously unknown details in its atmosphere. Mariner 10 also studied the structure and composition of the planet’s gas envelope. In general, its data has significantly enriched the treasury of scientific knowledge about Venus.

The first ever images of Mercury

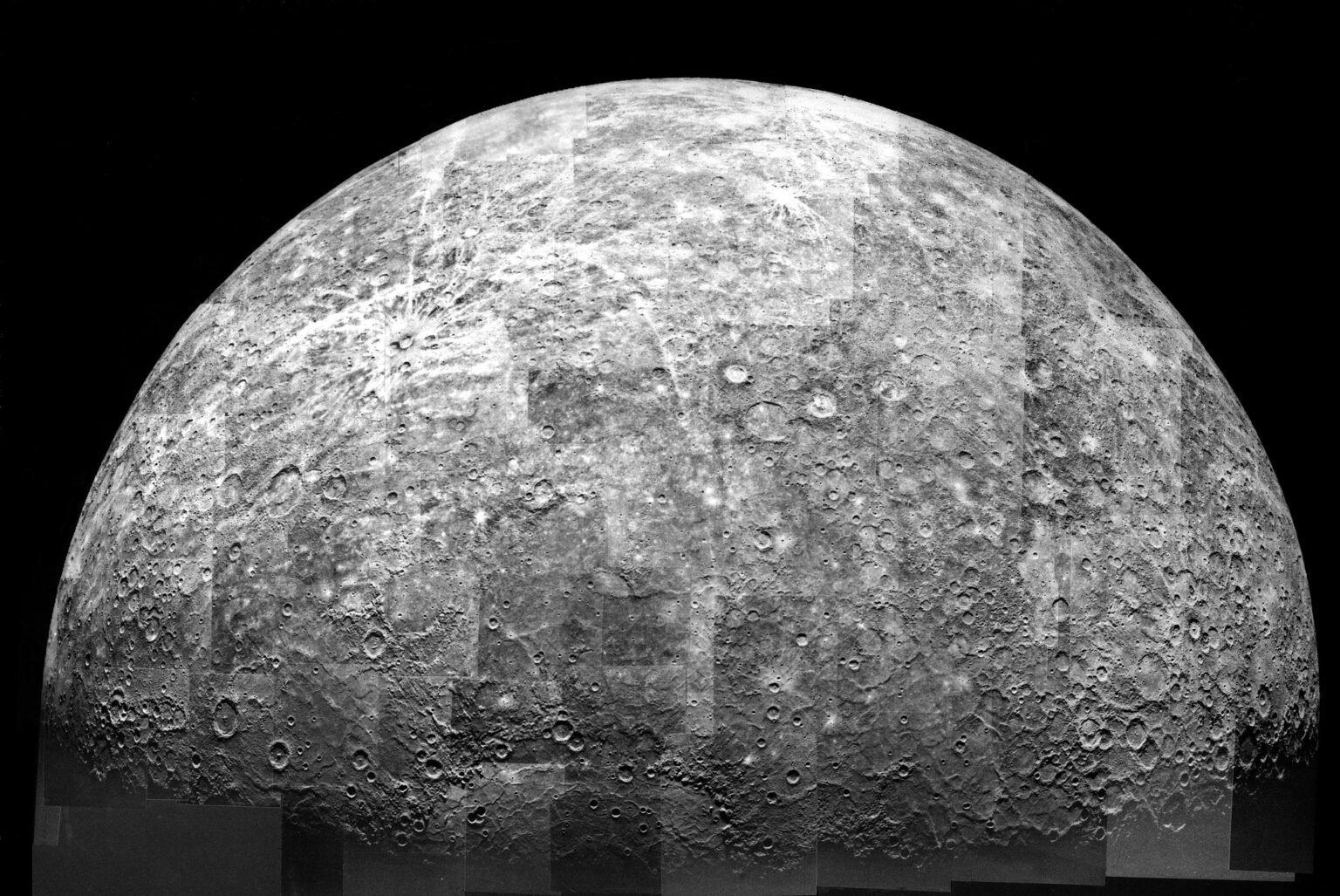

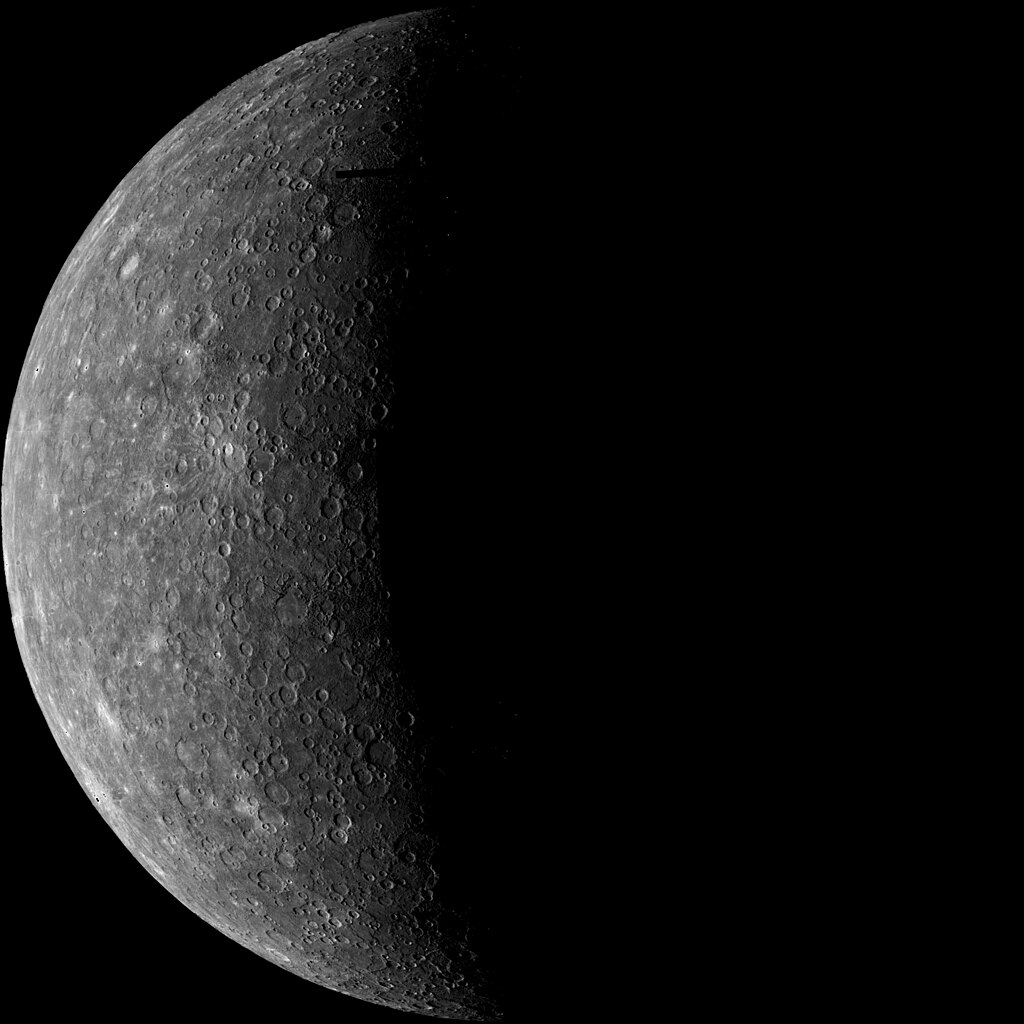

However, the main goal of the mission was not Venus, but Mercury. On 29 March 1974, Mariner 10 made the first ever flyby of the planet, capturing about 40% to 45% of its surface.

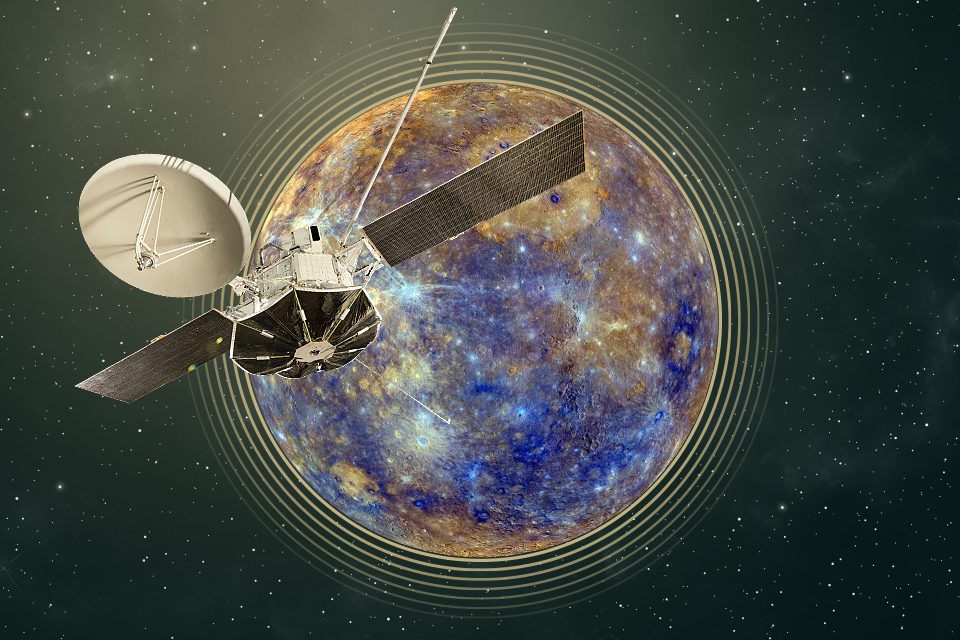

A mosaic of Mercury based on Mariner 10 images. Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The Mariner 10 images showed a heavily cratered surface that, at first glance, looks very similar to lunar landscapes. However, during further analysis, scientists found that the two bodies could not be called twins.

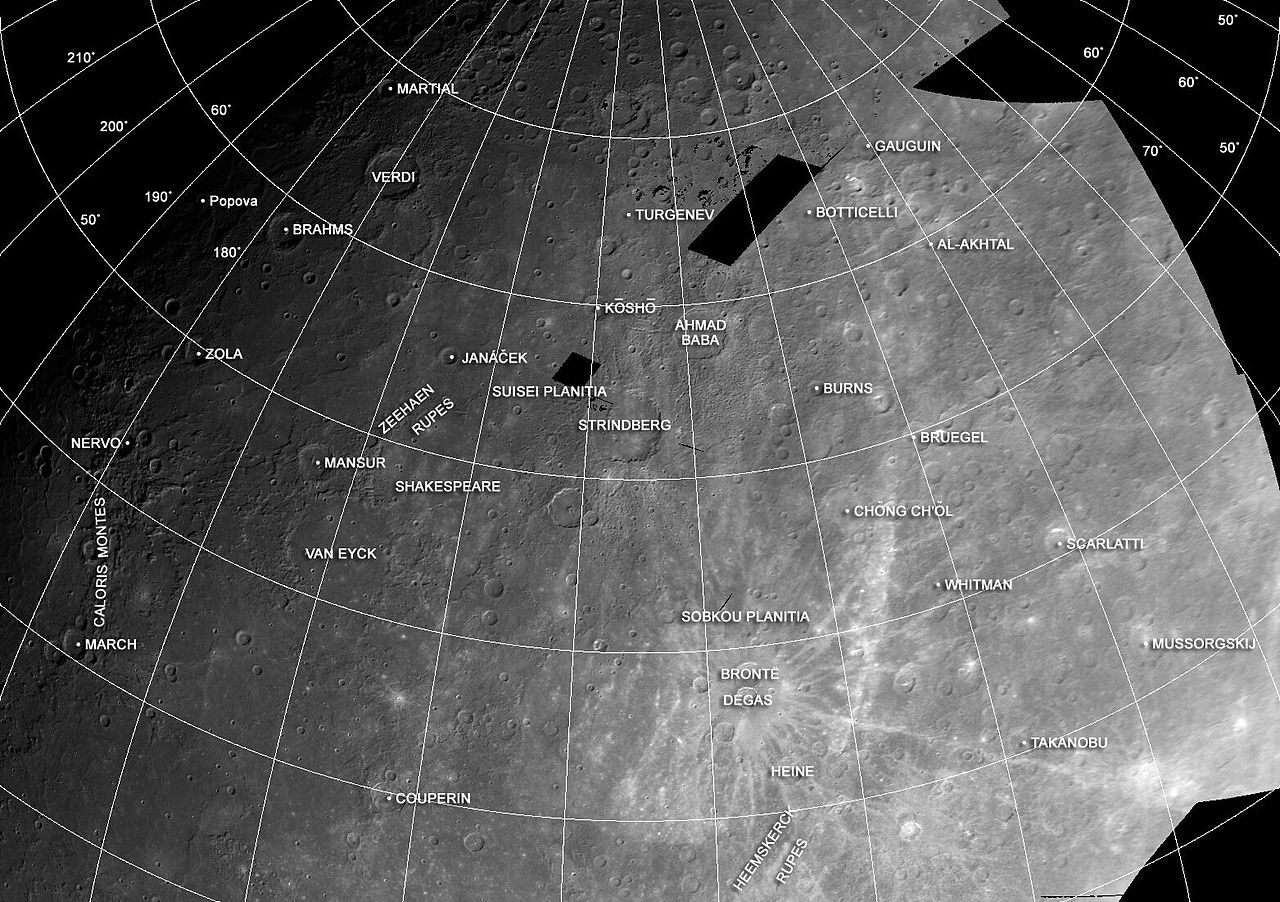

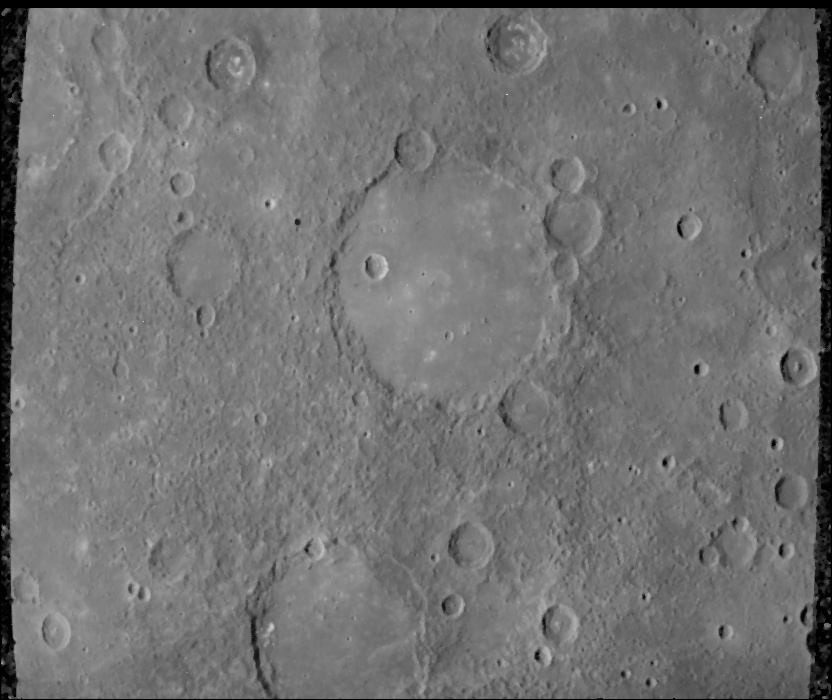

One of the areas of Mercury’s surface. Source: NASA/JPL

For example, Mercury does not have the large dark areas called seas that are typical of the Moon. Instead, it has many ledges stretching for hundreds of kilometres. These are kind of scars that arose due to the compression of the planet caused by the cooling of its core. As a result of this process, the surface area of Mercury has decreased by 1% over several billion years.

One of the areas of Mercury’s surface. Source: NASA/JPL

One of the most important discoveries of Mariner 10 was the discovery of a magnetic field on Mercury. Previously, it was believed that the planet rotates too slowly for a dynamo effect to occur in its interior. This is all the more surprising given that the larger Venus and Mars do not have a global magnetic field.

But what Mercury has virtually no atmosphere. The planet’s gas envelope is extremely rarefied and consists of particles captured from the solar wind or knocked out of the surface by the solar wind. In such conditions, atmospheric atoms collide with the planet’s surface more often than with each other.

One of the areas of Mercury’s surface. Source: NASA/JPL

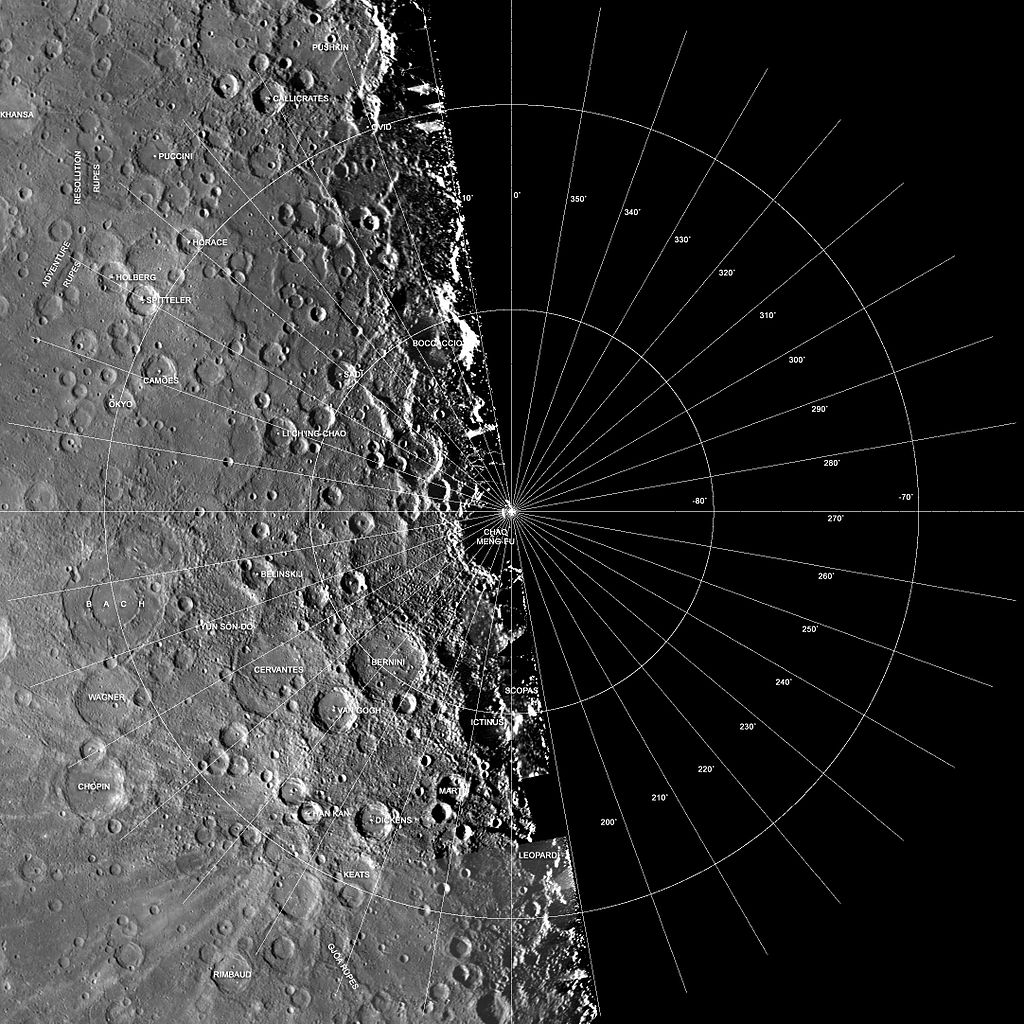

In September 1974 and March 1975, Mariner 10 made two new flybys of Mercury. By the time of the third visit, the spacecraft had almost exhausted the nitrogen reserves needed to operate the orientation system engines. Therefore, shortly after its completion, Mariner 10 was switched off. It is believed that the spacecraft is still orbiting the Sun and occasionally comes close to Mercury.

A portrait of Mercury compiled from Mariner 10 images. Source: NASA/JPL/USGS

The data collected by Mariner 10 laid the foundation for modern scientific understanding of Mercury. Its research was further continued by the MESSENGER spacecraft, which studied the planet from 2011 to 2015, and BepiColombo, which will enter orbit around Mercury at the end of 2025.