The eyes of astronomy enthusiasts across the world are currently glued to comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS). After its recent perihelion pass, its brightness has remained on a steady rise. At present, the best conditions for observing comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) are in the Southern Hemisphere, so plenty of stunning photos have been pouring in from that part of the globe. Next week, however, the comet will finally become visible in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

There is a chance, though, of C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) getting a new neighbor at the end of October. The potential new comet has a temporary designation A11bP7I and, if we get lucky, it might even briefly outshine Venus.

The Kreutz Sungrazer

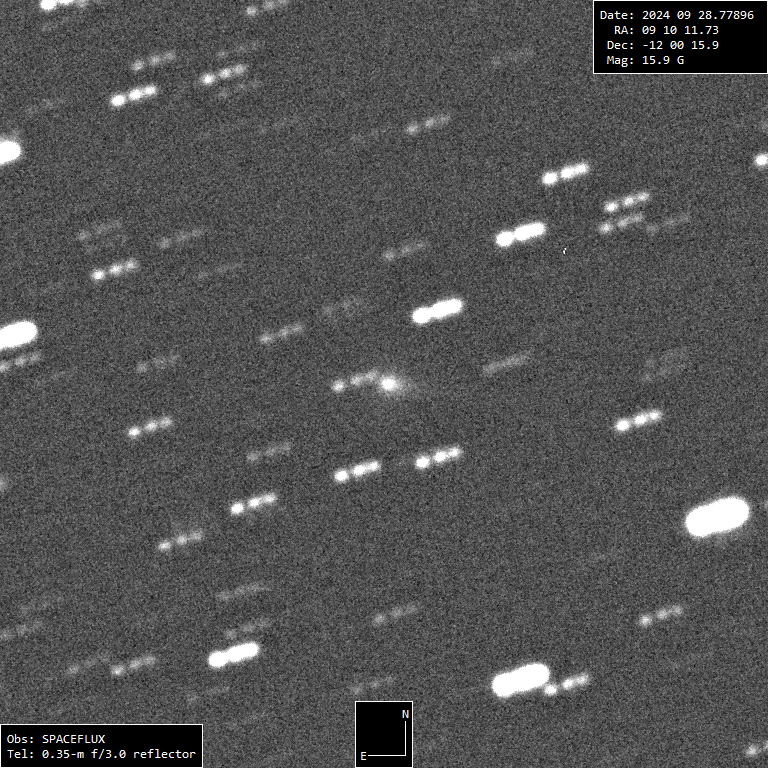

Discovered by the ATLAS telescopes on September 27, the A11bP7I immediately drew the interest of astronomers. Initial calculations classified this comet as a Kreutz sungrazer. Sungrazers are a family of comets that travel along similar orbits. All members of this family are believed to be fragments of the same great comet that likely broke up in in the 4th century BC.

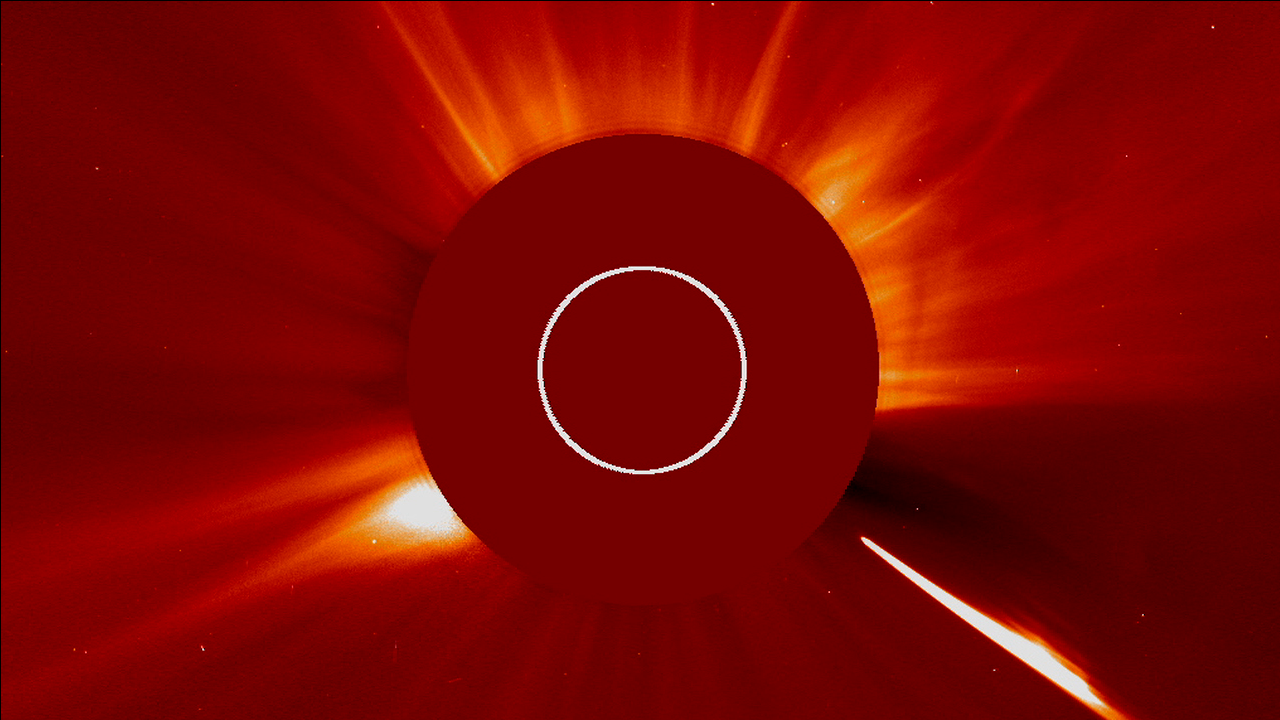

What makes Kreutz comets so distinct is the nature of their orbits that pass extremely close to the Sun in perihelion, exposing them to incredibly high temperatures. As a result, sungrazers expend significantly more dust compared to regular comets. That said, most sungrazing comets are quite small, so they can usually be spotted only by the SOHO space observatory.

Though there have been exceptions to the rule. Some Kreutz sungrazers are large enough to quite literally glow in perihelion and even become Great. The most recent event of this kind occurred in 1965 when comet C/1965 S1 (Ikeya–Seki) managed to generate such incredible brightness it remained visible even in daylight, right next to the Sun itself. Now, Ikeya–Seki is widely regarded as one of the brightest comets of the millennia.

Another similar case was comet C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) observed in 2011, though it could hardly outshine C/1965 S1 (Ikeya–Seki). Even so, when Lovejoy reached perihelion, its brightness matched that of Venus.

Is the New Comet Doomed?

As the A11bP7I was discovered only a few days ago, our knowledge of it is still fairly limited. But by measuring the comet’s brightness and taking previous cases of Kreutz sungrazers into consideration, astronomers are able to predict that our new guest might reach the magnitude of -6 in perihelion. If true, it will shine brighter than Venus.

The A11bP7I is expected to pass perihelion on October 28. What remains unclear about the comet’s orbit is how close it will actually pass by our star. Previous estimations have shown that this distance might prove to be shorter than the Sun’s actual radius. If that’s indeed the case, then the A11bP7I will quite literally crash into the Sun and perish.

But as the comet’s orbital parameters are uncertain due to the recency of its discovery, there still remains a possibility that its perihelion may occur farther from the critical point. While it might prevent the crash, it doesn’t guarantee the comet’s survival. Even with the less dangerous trajectory, the A11bP7I might still pass too close to the Sun and break apart. This is exactly what happened to C/1965 S1 (Ikeya–Seki) which broke into three fragments. Moreover, the nucleus of comet C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) completely disintegrated only a few days following the perihelion.

In any case, we will still be able to observe the new comet as it approaches perihelion. The conditions will be more favorable in the Southern Hemisphere, while the Northern Hemisphere might catch a glimpse of the comet’s tail. What follows next largely depends on the comet’s size, orbital parameters, and the strength of its nucleus. It’s highly likely that the A11bP7I is doomed. But should it withstand the power of our Sun, it might just put on a truly spectacular show as the second Great October comet.