NASA recently launched the Europa Clipper mission with the goal to study Jupiter’s moon Europa, believed to be one of the most likely worlds in the Solar System to have extraterrestrial life. Beneath its frozen surface, the satellite is hiding a vast ocean with more water than all terrestrial oceans combined.

Though Europa is of great interest to astrobiologists, it’s far from the only potentially inhabited object in the Solar System. In this article, we explore other planets and satellites that scientists hope could harbor extraterrestrial life.

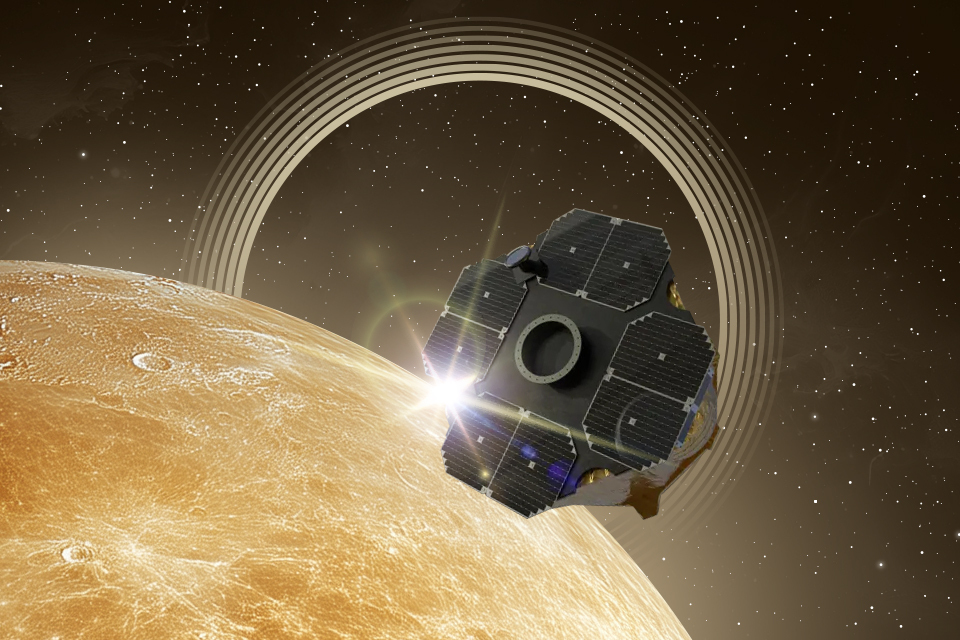

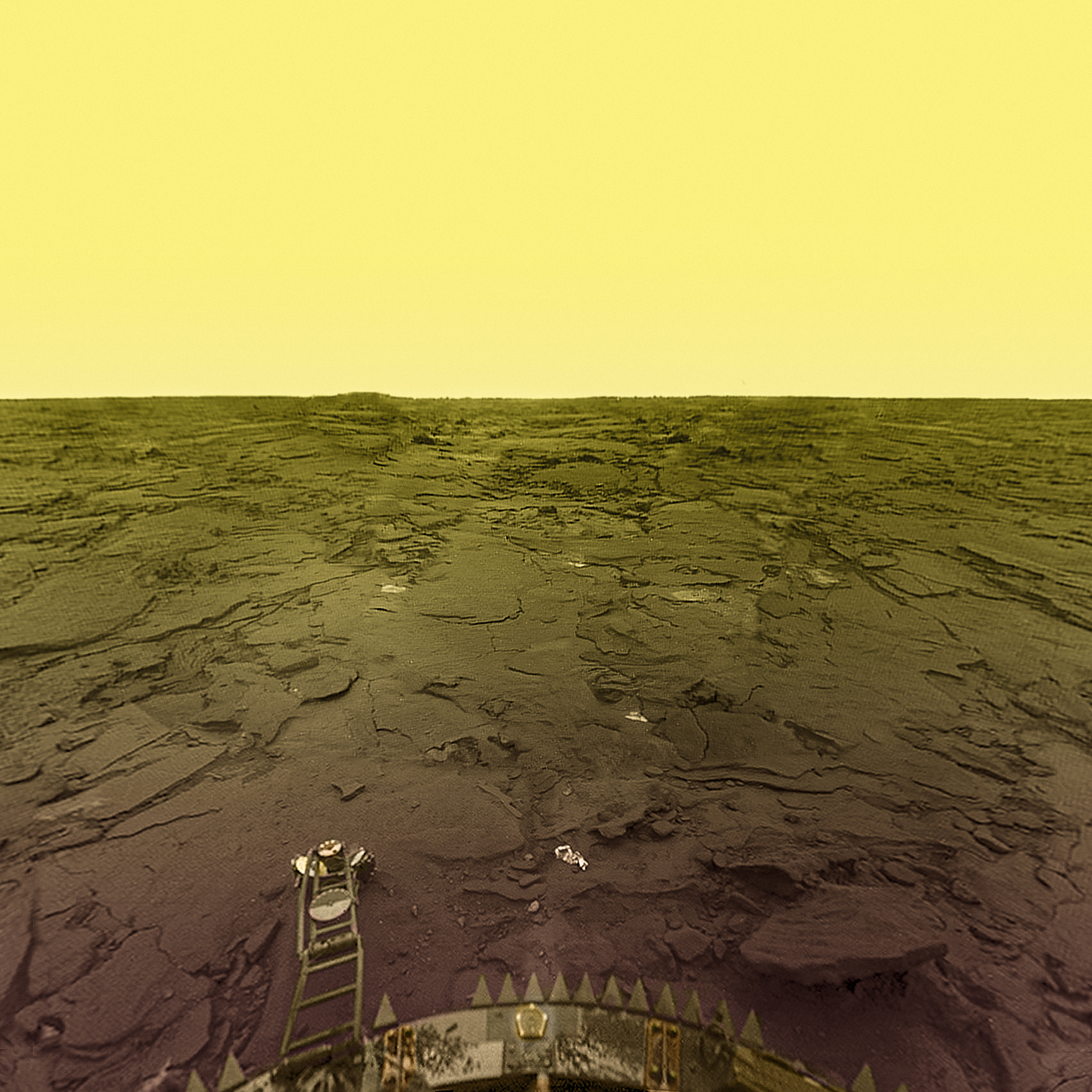

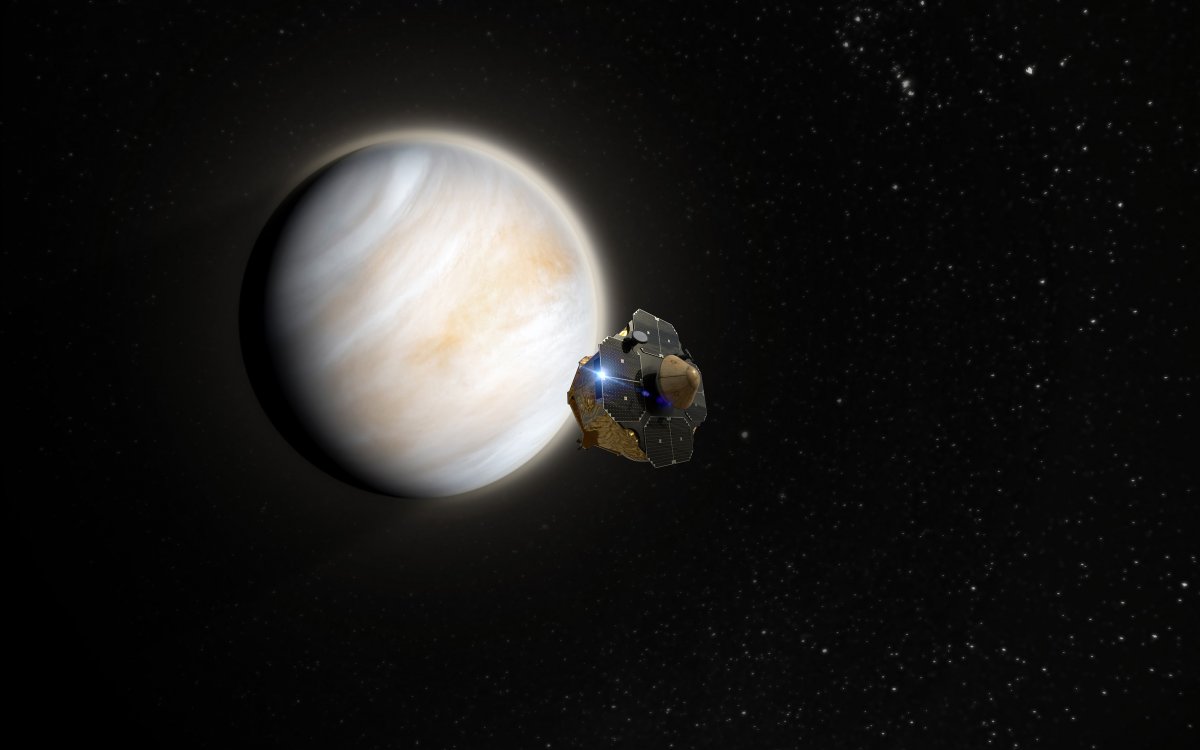

Venus

In terms of compatibility with human life, Venus is often seen as the most hostile environment in the Solar System. And there is merit to that. Due to Its high pressure and temperature — even more so than on Mercury — none of our probes managed to survive for longer than an hour. So how could it possibly sustain life?

However, it’s important to understand that, despite its hellscape appearance, Venus hasn’t always been this way. In fact, its physical characteristics are similar to Earth. Many scientists suggest that at some point in its past, Venus might have had fairly mild conditions, possibly even oceans.

Unfortunately, the Sun’s gradual increase in luminosity doomed Venus. Even if the planet had oceans in the past, they’ve all been ruthlessly vaporized by way of the greenhouse effect. But it didn’t happen overnight. In theory, microbial life on Venus could have had enough time to evolve and thrive in the upper atmosphere, where conditions are less harsh. Some scientists even speculate that it might still exist today on the Venusian surface.

Of course, all of this is largely supposition. In 2020, the discovery of phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere made a big splash, though the accuracy of these research results would later come into question. Still, the conversation around biomarkers in the planet’s atmosphere is very much ongoing. At the end of this year, Rocket Lab plans to launch the Venus Life Finder probe to search for organics in the Venusian atmosphere. Whether it will find any definite proof about the planet’s inhabitants or simply add more fuel to the fire with its findings — all that remains to be seen.

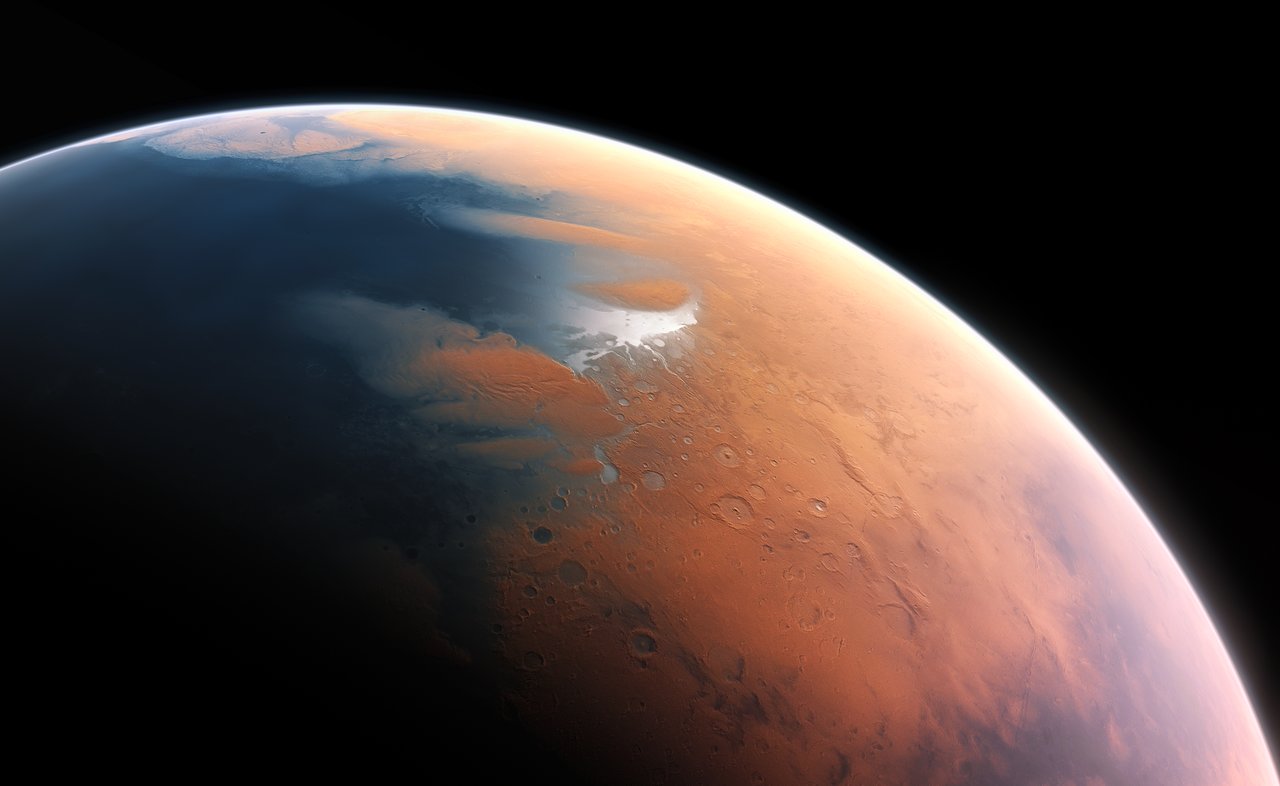

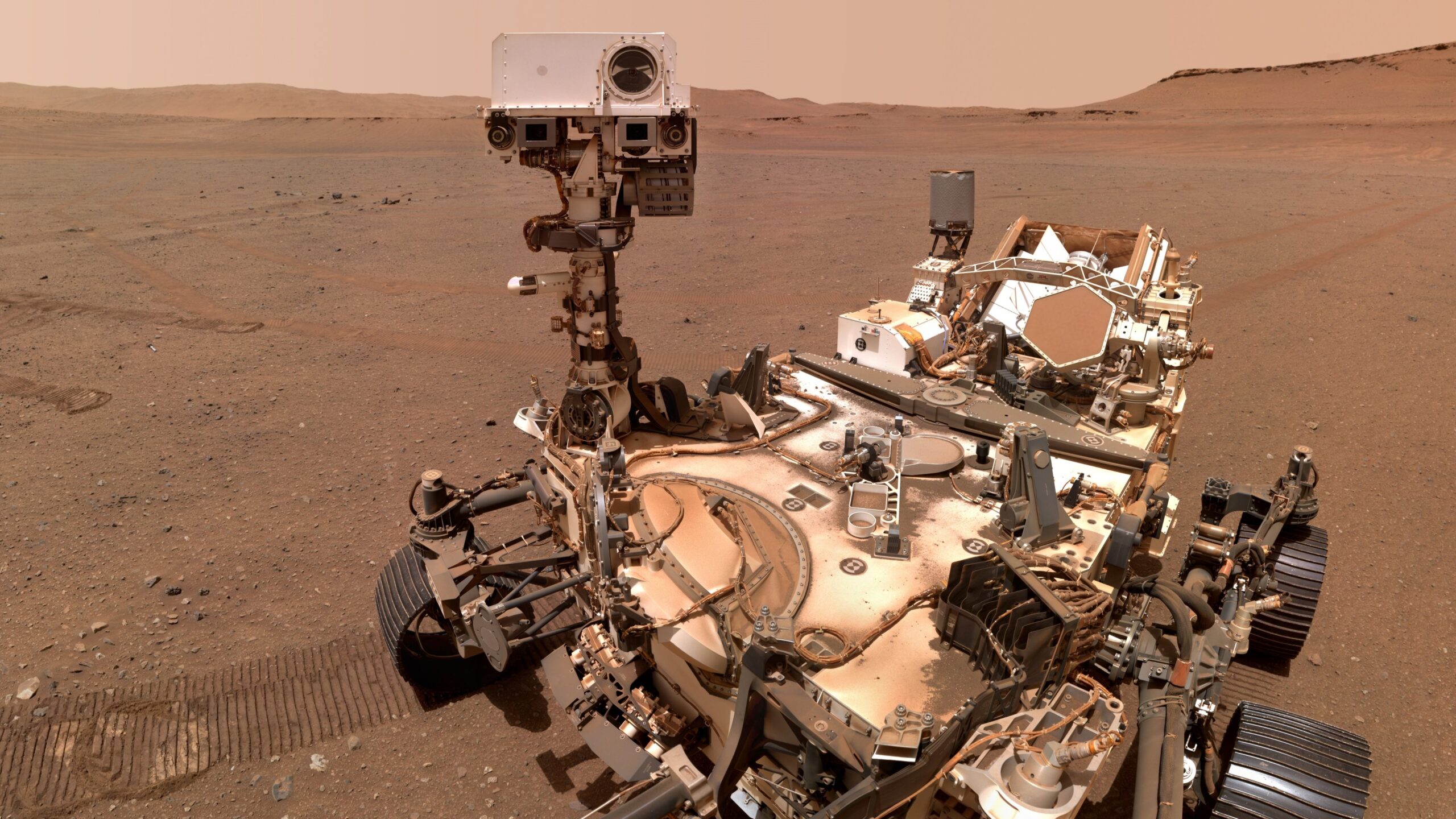

Mars

When it comes to life with human-level intelligence, the Red Planet has long been considered to be its most viable home world in the Solar System. Sadly, any romantic notions had long been dispelled by early Martian missions that showed this atmosphere-lacking planet to be an undeniably cold and deserted world.

However, the same probes also gave scientists hope. Mars may be a far cry from any pastoral idyll, but its distant past presented a completely different picture. The planet was warmer and had a denser atmosphere, while its surface had plenty of flowing water. This means it might have had the time to develop life. As the climate deteriorated with time, any existing life could have migrated underground. As it stands, all points to the fact that the planet could still hold subterranean pockets of water.

Of course, even if these hypothetical subterranean oases exist, we won’t be able to reach them for a long time. What we can do is search and study fossils on the Martian surface.

It’s easy to see why the Red Planet compels astrobiologists. To this day, it remains the only potentially inhabited world in the Solar System whose surface is accessible for extensive exploration at our current level of technological development. Its surface allows us to collect samples of soil and send them to Earth labs. This will be the primary goal of China’s Tianwen-3 mission planned for 2028. A similar project is in the works at NASA and ESA that could be ready to launch in the next decade.

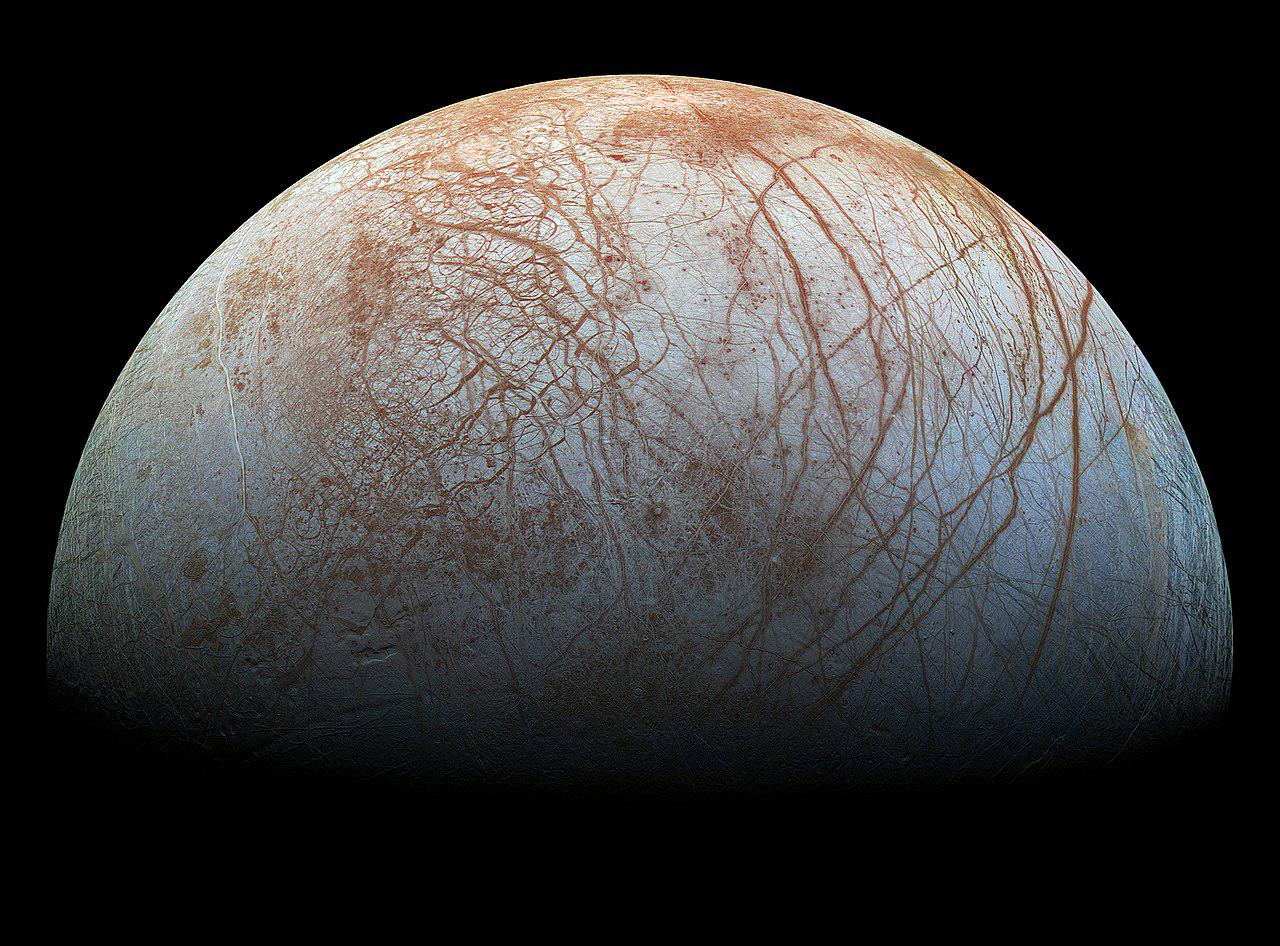

Europa

Though Mars remains the top billing star of astrobiological research, in recent decades the planet acquired quite a few serious rivals in the form of satellites of gas giants. Recent studies point to a number of them hiding liquid oceans beneath the surface. And as we all know, water implies the existence of life.

Jupiter holds the largest collection of such worlds, namely Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Out of these three, Europa is at the center of astrobiologists’ attention. Why such favoritism? Well, Europa is caught under strong influence of Jupiter and other moons, preventing its oceans from freezing over. Most likely, these forces are also behind Europa’s geysers that produce intermittent jets of water vapor.

Another key difference between Europa and Jupiter’s other icy moons is in the ocean itself. Europa’s ocean is not isolated and, according to current data, comes in direct contact with its rocky mantle that supplies vital matter for the formation of life. It’s also entirely possible that Europa’s ocean floor contains geothermal springs that act as oases. We will know more about the workings of the moon’s ocean in the upcoming decade when the Europa Clipper mission reaches Jupiter.

As for Callisto and Ganymede, their oceans appear to be isolated, reducing the probability of life. In Callisto’s case, the ocean is separated from its rocky mantle with a layer of ice. Ganymede, on the other hand, resembles a sandwich. As per current models, its depths consist of alternating layers of water and various forms of ice.

Nevertheless, both worlds are still viewed as potentially habitable. Whether there’s merit to such hopes will be explored further by the JUICE mission, scheduled to launch for Jupiter in 2031. It will study Ganymede and Callisto more extensively, allowing for a detailed image of their internal structure as well as the properties of their subterranean oceans.

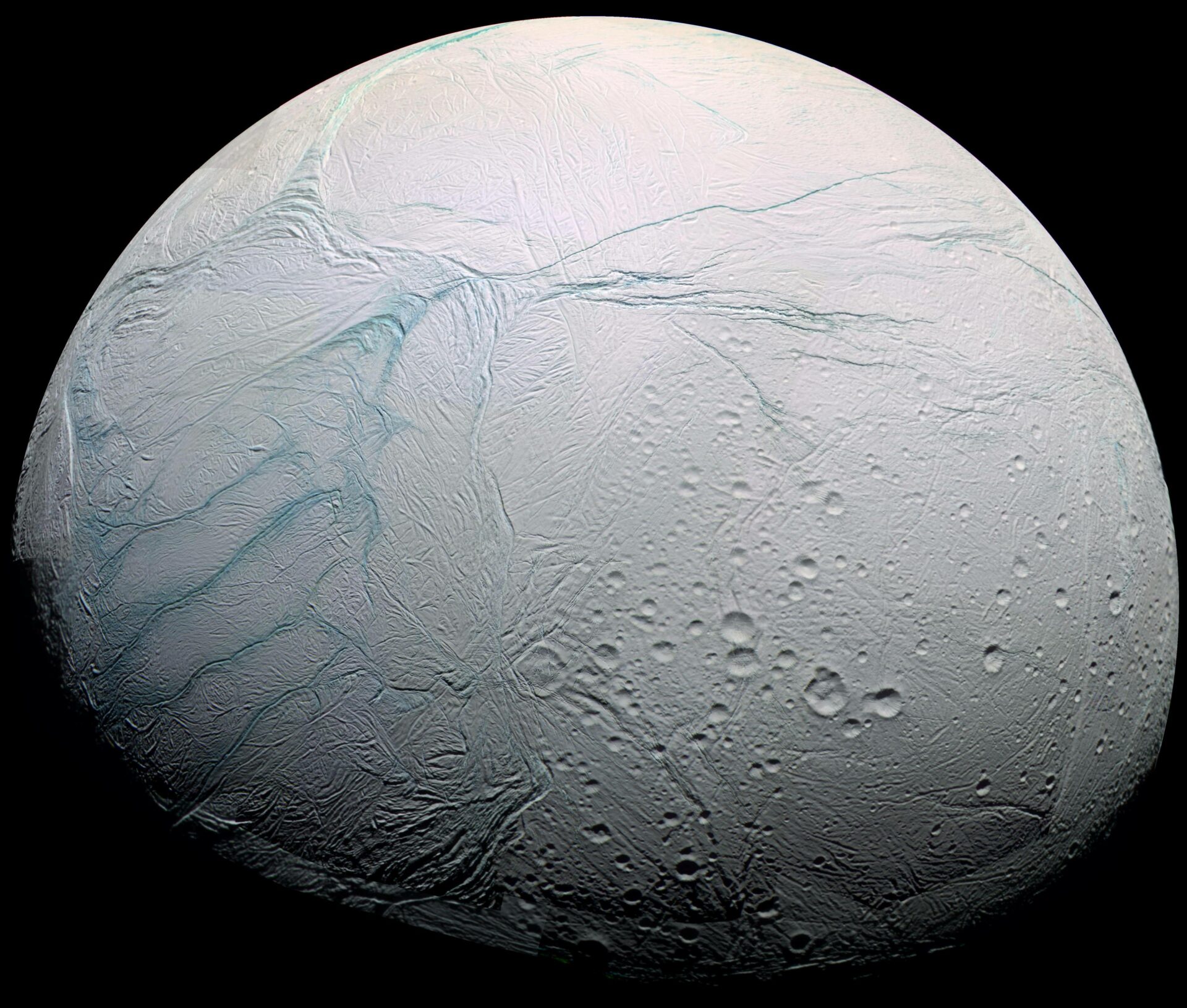

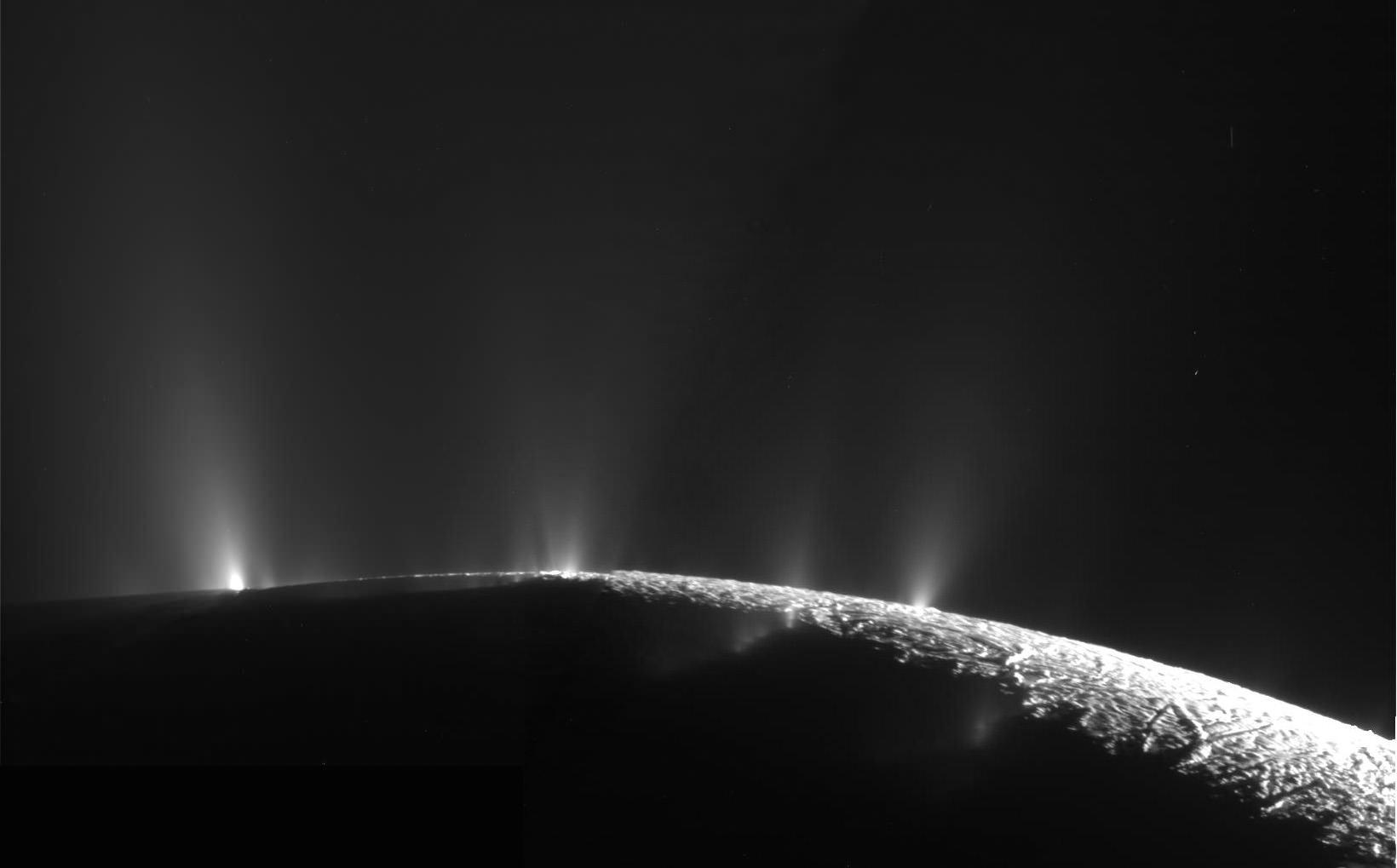

Enceladus

If any icy world could rival Europa in the eyes of astrobiologists, it’s Enceladus. Despite its tiny size, measuring only 323 miles (or 520 km) in diameter, the moon is incredibly active. Its South Pole is rife with geysers projecting water into space in such large amounts that it’s formed an entire ring around Saturn.

Current data points to subterranean oceans as the source for this water. The theory provides us with an exciting opportunity to send the probe in order to collect research samples from Enceladus’ geysers.

This is what Cassini did during its mission. Sadly, its engineers hadn’t foreseen this opportunity and didn’t think to equip the probe with necessary instruments for extensive astrobiological analysis. That said, Cassini still collected plenty of compelling data on the chemical composition of Enceladus, further exciting scientific interest. We now know that the moon’s ocean contains salts, organics and even hot springs along its floor.

This makes Enceladus one of the most prospective worlds for the search of extraterrestrial life in the Solar System. A number of space agencies are currently developing missions with the purpose to analyze the moon’s chemical output, though these projects are yet to be approved. In terms of scientific interest, there is no doubt that Enceladus will one day get its own personal researcher in the face of a dedicated probe.

Titan

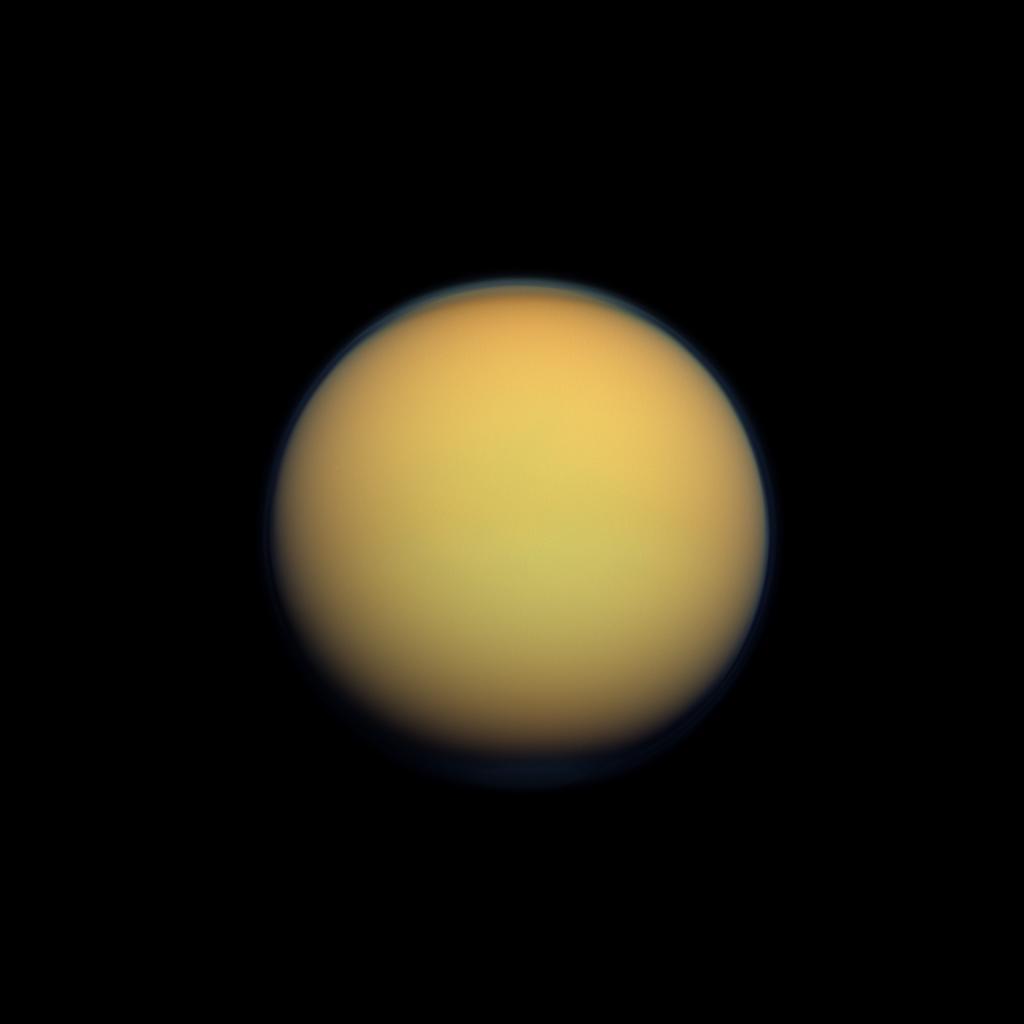

Apart from Enceladus, Saturn offers another rather fascinating world for astrobiologists — Titan.

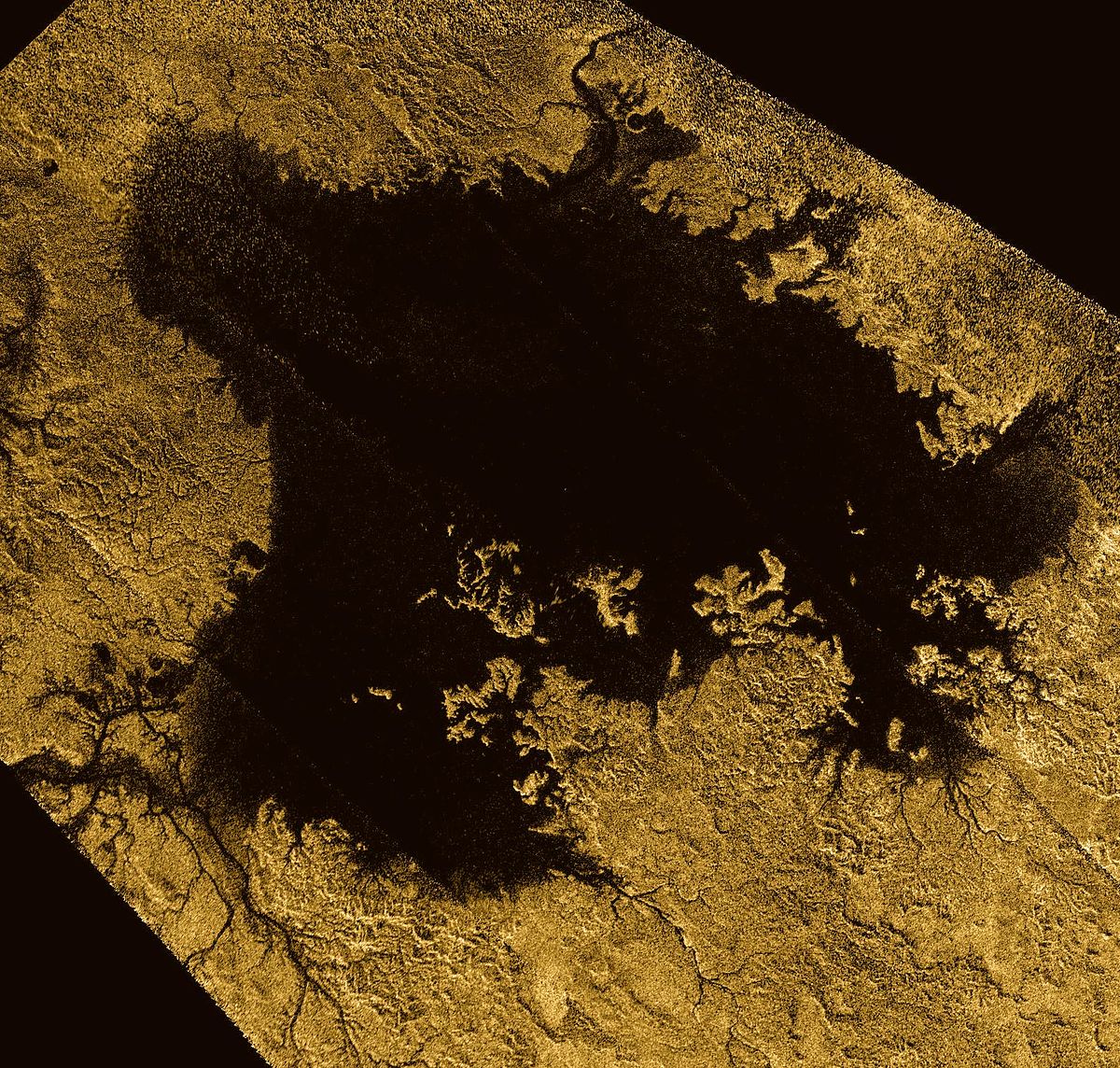

Without any risk of exaggeration, Titan is completely unique. Not only is it the only satellite in the Solar System to have an atmosphere, it’s also the sole object (aside from Earth) to support a complete hydrologic cycle on its surface. Except rather than water, it’s a mix of liquid hydrocarbons — mostly ethane and methane. The satellite’s North Pole features entire seas brimming with these compounds.

Whether such extreme conditions can sustain life, now that’s a real million-dollar question. Many scientists believe that Titan is too cold for a biological evolution, though not everyone is of the same thought. What’s clear is that if Titan’s surface does harbor life, its biochemical pathways are likely completely different from our planet’s. This simple fact further fuels scientific interest in the satellite.

Aside from its surface, Titan may also contain life in its depths, most likely within a hidden subterranean ocean made up of water and ammonia. So if we were so inclined, we could imagine two completely separate ecosystems co-existing on Titan, where each stems from a different biochemical cycle.

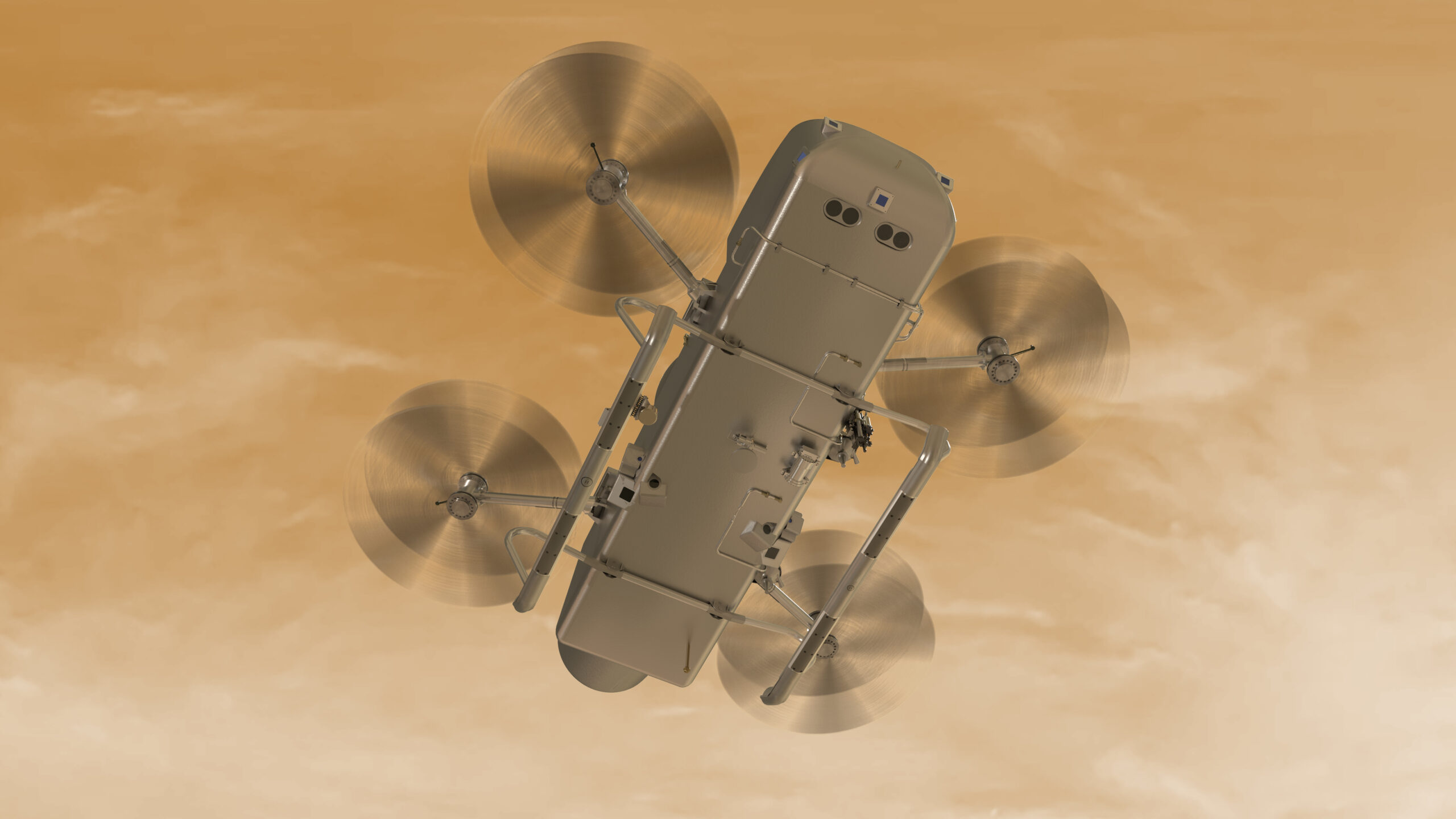

We will know about this satellite in 2034, when the Dragonfly mission reaches its destination and sends a drone to study Titan’s atmosphere and surface. The collected data will help scientists estimate the likelihood of extraterrestrial life there with more accuracy.

Triton, Ceres, and Pluto

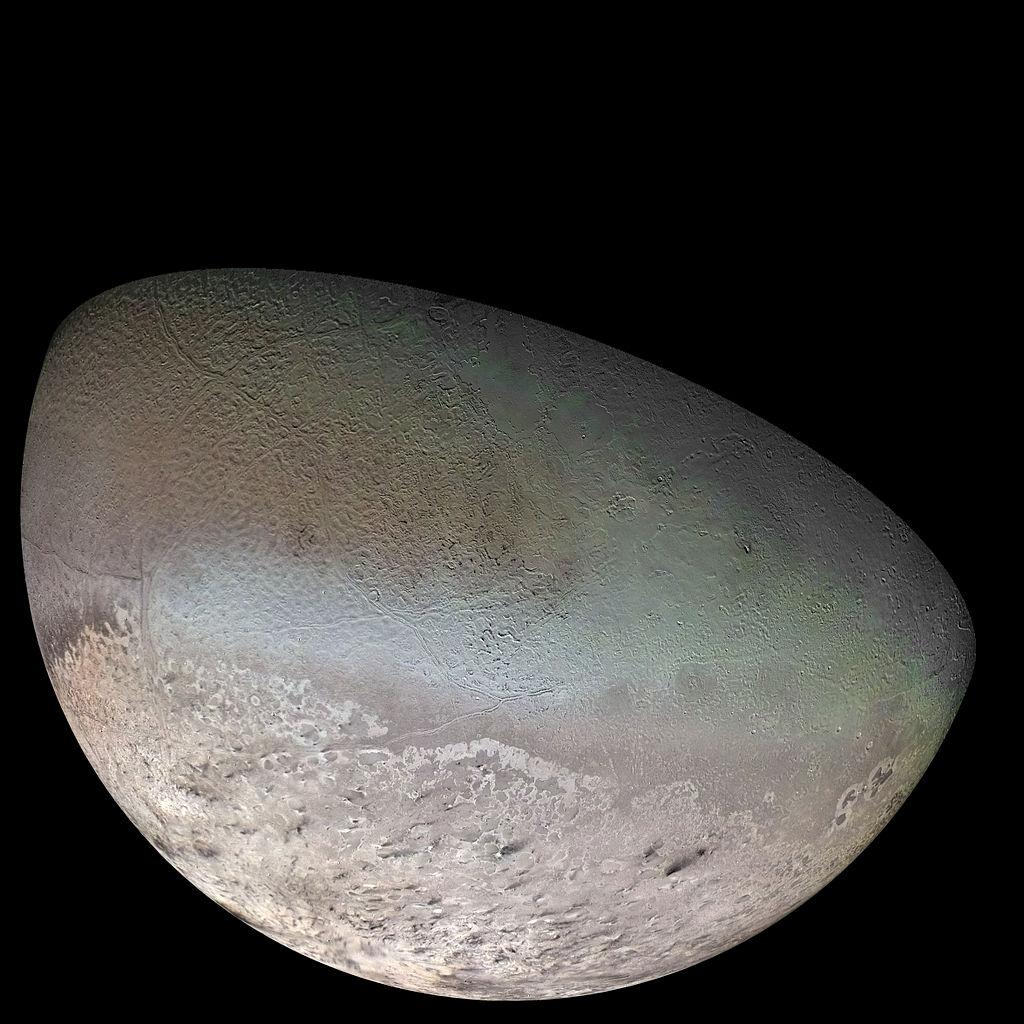

But there are more options for potentially inhabited worlds in the Solar System. Uranus and Neptune also have icy moons that could be concealing whole oceans, with Triton being of particular interest due to its cryovolcanic activity.

Dwarf planets could also have subsurface oceans. Ceres is believed to have had a muddy ocean in the past, and some researchers theorize that it didn’t entirely freeze over. Another point of interest is Pluto. Its cryovolcanic activity indicates that the planet might be hiding at least some liquid reservoirs beneath the surface. And we could only guess what kind of revelations await us on the distant objects in the Kuiper belt.

All we can know for sure is this: the range of potential life in the Solar System might be significantly wider than we thought even a few decades ago. So whether we are alone in the Solar System is a question that will likely remain open for a while yet.