The solar corona is much hotter than the layers of the Sun’s atmosphere below it. The main mechanism that allows it to heat up so much is Kinetic Alfvén waves. Recently, scientists were able to investigate how exactly they contribute to the redistribution of energy in the plasma.

Hot solar corona

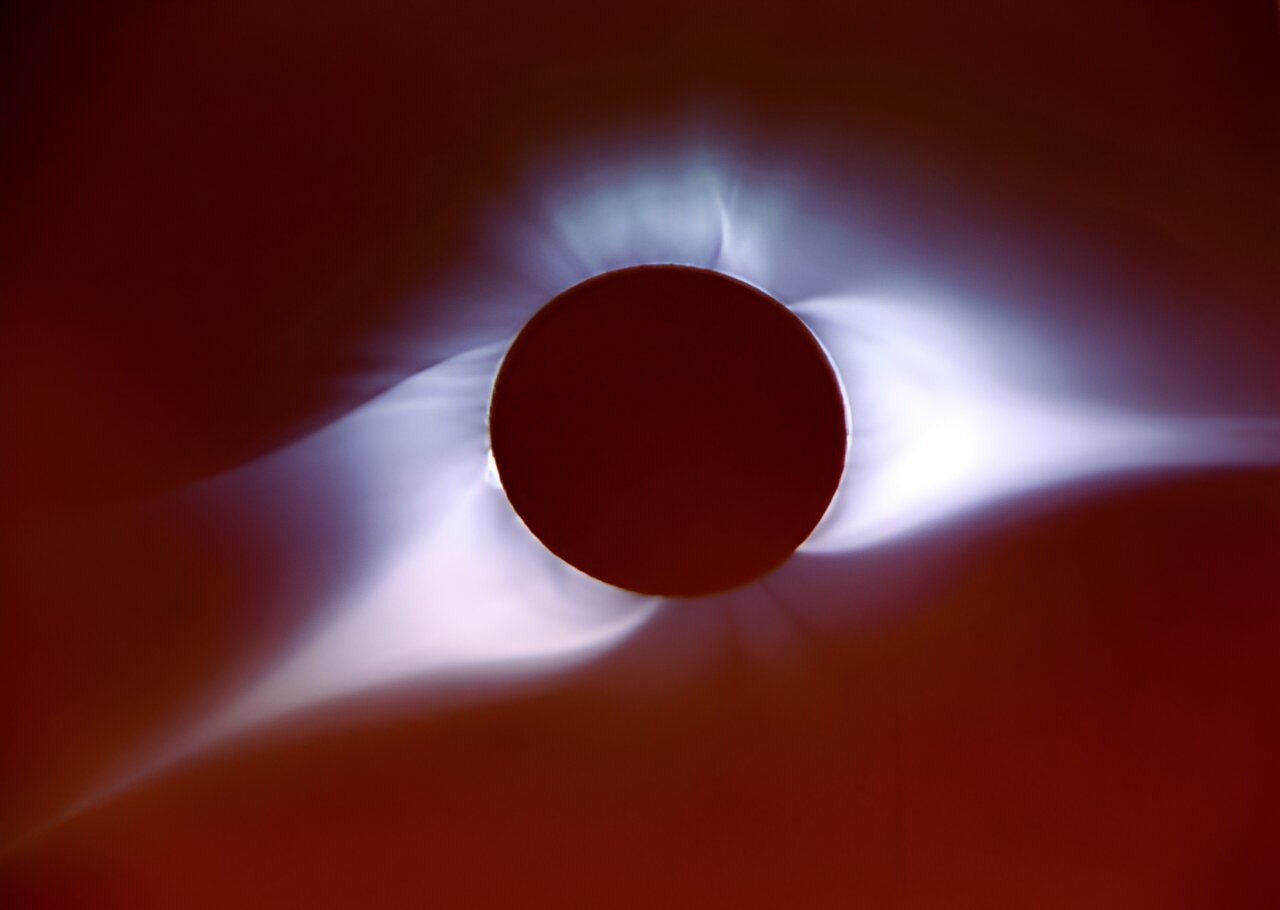

The solar corona is the outermost layer of our luminary’s atmosphere — the same rays that are clearly visible during an eclipse. It extends up to 8 million kilometers from the star’s surface and is incredibly hot. Its temperature can reach up to a million degrees Celsius.

However, the main mystery is not in this, but that the underlying layers, which scientists usually call the surface of the Sun, is actually much colder — “only” 6500 ° C. Recently, Syed Ayaz, a graduate student at the University of Alabama, published a study in which he was able to explain in some detail how this can happen.

Scientists have no proven theory as to how energy can flow from a colder body to a hotter one. However, for quite some time now, Kinetic Alfvén waves have been considered as the main candidate for heating the solar corona.

What the study found

In the new study, the young scientist focused on investigating how Kinetic Alfvén waves propagate in the medium of the Sun’s outer layers. His work relied on data on the behavior in these regions of magnetic fields and charged particles collected by the Viking and Freja satellites.

Kinetic Alfvén waves arise from the action of fluxes in the Sun’s plasma. They are oscillations of ions escaping into the photosphere and are scattered there while transferring energy. And now scientists know how this can be done even if the environment is heated to incredible temperatures.

It is caused by a phenomenon known as Landau damping. When a wave propagates through space, it oscillates at a certain speed. Charged particles in the Sun’s corona also have their own velocity and are very high, because their kinetic energy is proportional to temperature.

The latter transfers energy to the first even without a direct collision. And since the frequency of oscillation of Kinetic Alfvén waves is large, they are able to accelerate electrons in the plasma even when the same are overflowing with energy. In a new study, scientists have shown that this is how they dissipate very quickly in the outer layers, significantly affecting their dynamics.

According to phys.org