Exactly fifty years ago, on December 11, 1972, the Challenger module made a soft landing in the Taurus-Littrow area. Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt were on board. They were the last people visiting the Moon in the 20th century.

The last flight of the Apollo program

Originally, Apollo 17 was not intended to be the last manned lunar mission. Three more expeditions were envisaged, and NASA was preparing for them. Saturn V rockets and spacecraft needed for missions were in production, and landing sites were also preliminarily determined.

However, severe funding cuts for NASA and the aftermath of the Apollo 13 explosion led to the phasing out of the Apollo 20, Apollo 19, and Apollo 18 missions. As a result, Apollo 17 was the last flight of the American lunar program.

The landing site of the Apollo 17 expedition has been the subject of controversy. NASA wanted to get the most scientific data from the final lunar expedition and planned to land the craft in an as yet unexplored type of terrain. Harrison Schmitt, who was part of the crew, insisted on landing in Tsiolkovsky Crater on the far side of the Moon. Unfortunately, NASA rejected this ambitious option due to financial considerations, as it would require a relay satellite to be launched to provide communication with such a mission.

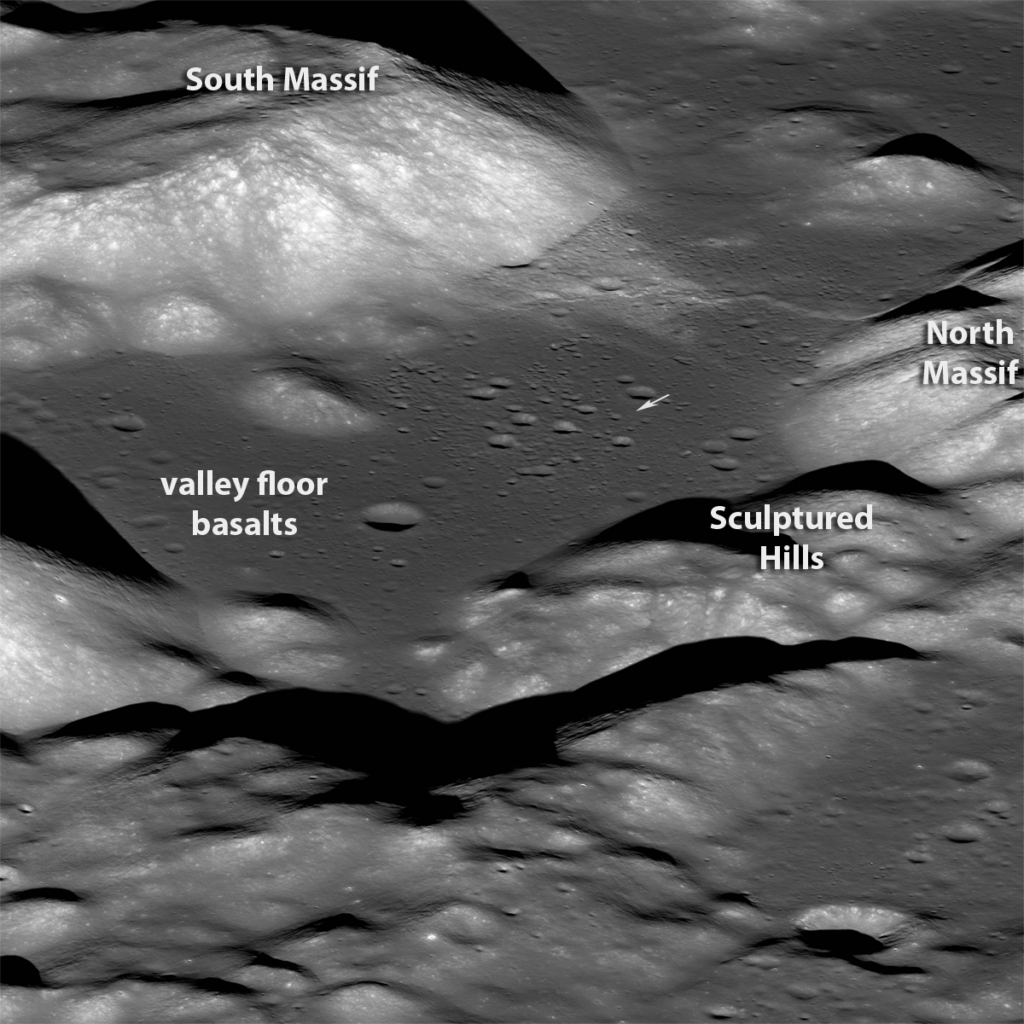

As a result, the choice was made in favor of the Taurus-Littrow area. It is a valley, which is surrounded by mountains on three sides and has traces of lava flows. Scientists were attracted by the opportunity to obtain both younger and ancient samples of lunar rock, unlike those brought back by astronauts of other missions.

The first scientist on the Moon

Apollo 17 went down in history not only as the last manned lunar mission to date. It became the first and so far the only expedition brining a professional scientist to the Moon.

The fact is that the crews of all previous Apollo expeditions consisted of astronauts who were military pilots before joining NASA. Of course, before the flights, they underwent geological training, but still they could not be called scientists. The scientific community actively criticized NASA because of this. When it became clear that Apollo 17 would be the last lunar expedition, the pressure on the organization increased so much that it had no choice but to include a professional geologist in its crew.

The choice fell on Harrison Schmitt. He joined NASA in 1965 as part of the so-called first group of scientists-astronauts; Schmitt was engaged in the geological training of all Apollo crews. After each mission, he participated in the review and evaluation of the lunar samples brought back and assisted the astronauts with the scientific aspects of their flight reports. He also thoroughly studied the Apollo command and lunar modules. Thanks to all the above factors, NASA included him in the final expedition.

Apollo 17 mission`s records

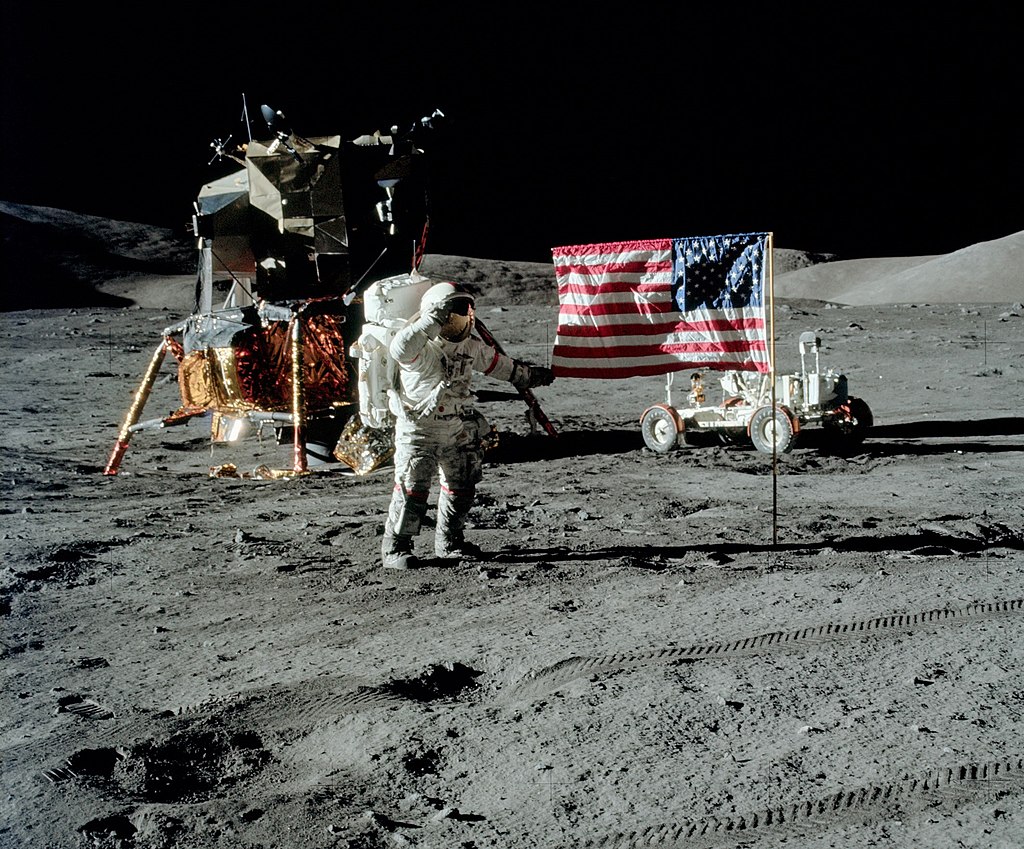

Apollo 17 flew up towards the Moon on December 7, 1972. It is interesting that this was the first (and at the same time the last) night launch in the history of the program. After undocking, the lunar module with Cernan and Schmitt made a safe landing in the planned area. The command module, piloted by astronaut Ron Evans, remained in a selenocentric orbit.

Cernan and Schmitt spent 75 hours on the surface of the Moon. Of these, 22 hours were spent on off-ship activities. During three trips to the surface, Cernan and Schmitt conducted a series of experiments and installed a set of scientific equipment that worked until 1977.

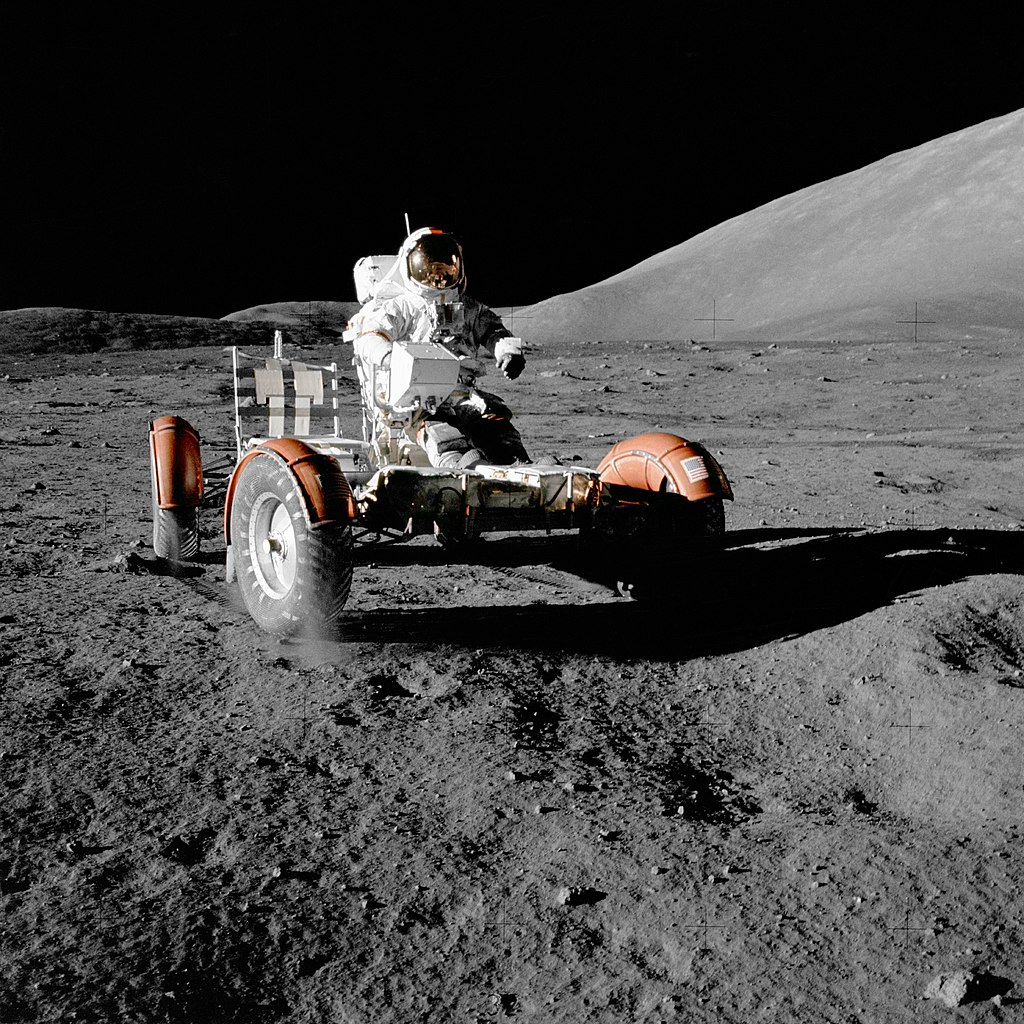

Thanks to the presence of the rover, the astronauts traveled 35 km on the lunar surface, setting a new record. In total, they collected 110 kg of rocks, which was also a record acquisition. According to popular opinion, of all the samples collected by manned expeditions, it is the soil samples brought by the Apollo 17 crew that have the greatest scientific value (of course, the main credit for this belongs to Schmitt).

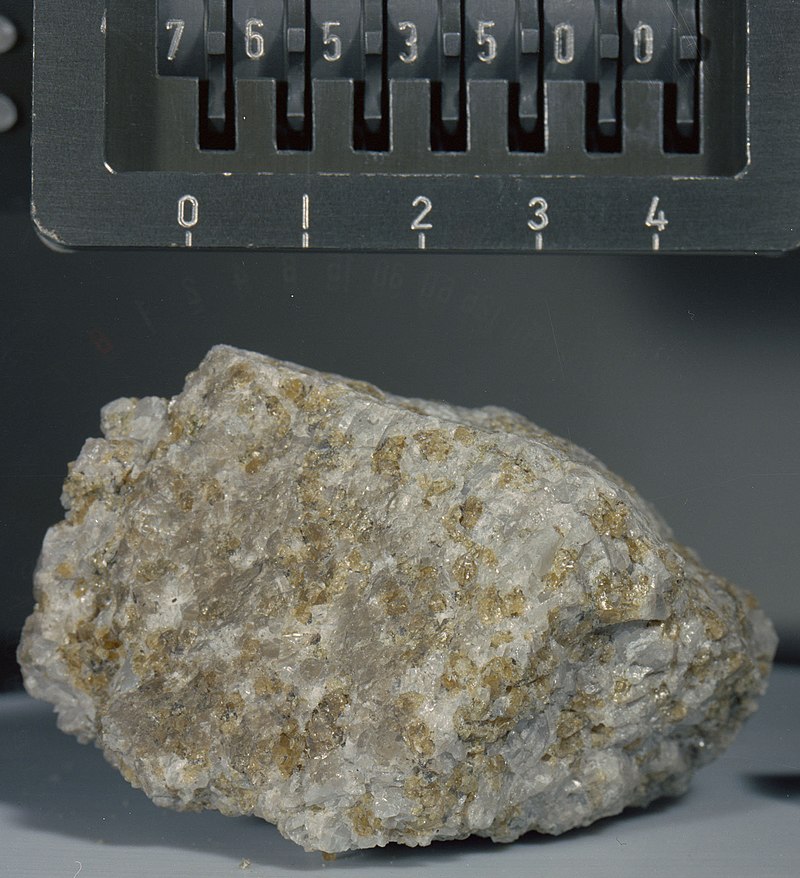

According to many researchers, the main finding of the expedition was a sample designated Troctolite 76535. This is the oldest fragment of lunar rock that was not exposed to external influences. It literally became a cornerstone in proving the theory that the Moon once had its own magnetic field. Astronauts also managed to find a fragment of rock knocked out of the Tycho crater. Its analysis showed that the impact formation was created 108 million years ago.

Farewell to the Moon

At parting, Cernan and Schmitt installed a memorial plaque on the surface of the Moon with an image of the Earth and the following inscription: “Here Man completed his first exploration of the Moon, December 1972, A.D. May the spirit of peace in which we came be reflected in the lives of all mankind.”

Before entering the lunar module for the last time, Eugene Cernan uttered the following words: “As I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come – but we believe not too long into the future – I’d like to just (say) what I believe history will record. That America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17. “

Cernan later described his final moments on the Moon:

“I hardly remember my first steps on the Moon, but I remember the last ones very well. Together with my partner, geologist Harrison Schmitt, we spent three days on the Moon. Ronald Evans, the command module pilot, was waiting for us in orbit. We already realized that Apollo 17 was the last lunar mission, but during those three days I somehow did not think about the fact that I would be the last person to stand on the surface of the Moon.

Since the very beginning, it was known that Schmitt should be the first to enter the manned module that would take us from the surface of the Moon back into orbit. As we were leaving, he quickly climbed the stairs and disappeared inside, and I climbed three or four steps and turned around.

At that moment, for some reason, I remembered how as a child I used to go to my grandfather’s farm in the summer, and then when my parents came to get me back home, I went with them, but all the time I turned around and looked at my grandfather’s house. Standing at the entrance to the lunar module, I felt something very similar. Meanwhile, though leaving my grandfather’s farm, I always knew that I would return next summer, I would never return to the Moon. Someone might come back there someday, but not me.

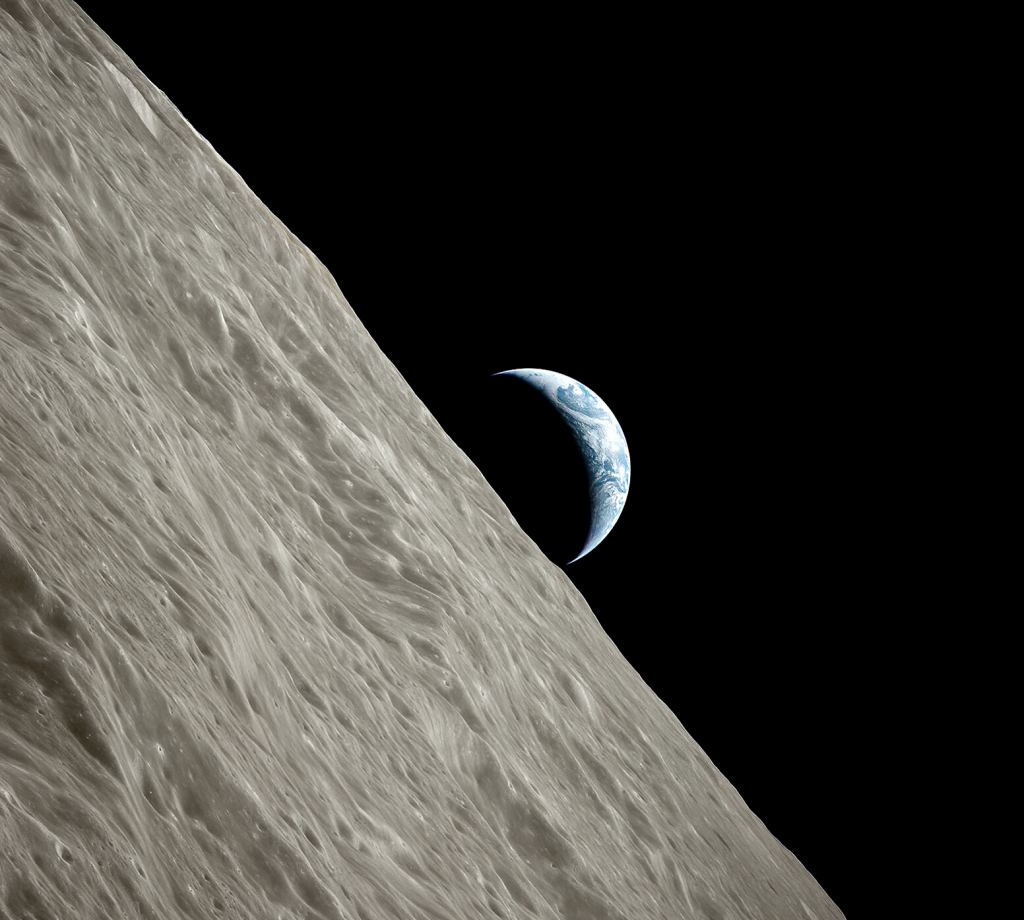

I stood at the entrance to the module, looked at the Moon, looked at the Earth. There, on the Moon, you are constantly looking at the Earth. From there, from space, it is piercing. It is more like a picture, a blue spot painted on a black background. It is so close and so small that you begin to think: you can just reach out and take it with you — to show your loved ones — this is what it looks like.

…Did I feel fear? From the very beginning and until now, I answer this question monotonously: we were too busy with things to get scared. All we felt was greatness. After all, the Moon is the Moon. On Earth, you can conquer the highest mountains and descend into the depths of the ocean, but you are still on Earth. When you just take a step on the surface of the Moon, you realize that all your earthly achievements are nothing, because you are no longer on Earth.

…Having returned to Earth, I thought that this was not the end, but rather the beginning. I was sure that despite the end of the Apollo program, by the end of the 20th century, there would be a habitation on the Moon and that all six lunar module landing sites — especially Apollo 11’s — would have monuments erected.

I was sure of it. Maybe that’s why I left my favorite camera on the Moon, a Hasselblad 500. Why did I do that? So that researchers, who I hope will return to the Moon one day, can see how cosmic radiation can affect the lens. Am I sorry about the camera? Of course, not. In addition to it, I also left on the Moon something I am really proud of: the three letters “T”, “D” and “C”. Those are my daughter’s initials”.

The Apollo 17 lunar module was launched from the Moon on December 14. Cernan and Schmitt boarded the command module, after which the ship headed back to Earth. On the way home, the astronauts took one of the most iconic space photos in history, called The Blue Marble. On it you can see the fully illuminated Earth.

A capsule with three astronauts successfully landed in the Pacific Ocean on December 19, 1972. This was the end of the Apollo program.