Picture a scene: you, a seasoned astronomy enthusiast, are dying to show someone a fascinating nebula, or, say, a legendary comet, and so you aim your telescope at the right spot, invite them to glimpse at the wonder and… all you get in response is, “What am I supposed to be looking at?”

This scenario is likely familiar to most passionate astronomers. But introducing a complete novice to the science of celestial bodies should begin with more familiar, easy to spot objects. The kind that appears in the night sky at least once a month and makes it easily to find, even for inexperienced beginners and their relatively small 20-30x magnification telescopes. So let’s take a look at some of these celestial objects.

The Moon

As a guest, our natural satellite is rather inconsistent (after all, some nights it even refuses to show up), often running late for the twilight hours, which beginner astronomers prefer for their first forays into observation. But for about ten days a month, lunar observational conditions align almost perfectly, and can only be skewed by the weather. If you plan to catch the Moon for yourself, it’s best to study the lunar calendar and weather forecast a few days prior to the first quarter phase. While shifting into its full phase, the Moon appears in the evenings, and as it begins to wane, it gradually crawls toward the morning sky.

The Moon is very easy to find, owing to its intense brightness and the fact that it isn’t a luminary point, but a distinct shape. Its crescent diameter measures 5° from tip to tip, and changes depending on its orbital position. Often you could see it even in daylight. Our satellite is at its brightest when it’s full, but it can offer quite a few exciting sights even during its first and last quarter phases. In particular, when the terminator — the moving boundary between the daylit and night sides — divides the Moon’s surface at a halfway point. It’s there, in the now illuminated southern (or lower) part of the Moon, that you can find a huge number of craters, some visible even with 7x binoculars. On the border between shadow and light, the uneven terrain casts long, distinct shadows, creating a uniquely striking texture.

For the full Moon, small observational instruments can only show the largest and most prominent craters. This phase is best suited for studying lunar seas and the giant Ocean of Storms that takes up a considerable portion of the satellite’s visible surface. Notably, the full Moon also plays a major part in solar eclipses, but this phenomenon is such a rare event that it wouldn’t make sense to go into it any further.

The Sun

Our daytime star got this name precisely for its consistent appearance in daylight — provided the weather is clear. Subpolar regions are one exception to this, where the Sun disappears for two to three months in a row, though these areas aren’t that densely populated. By way of dubious compensation, the Sun also doesn’t set there for roughly the same period.

Finding the Sun won’t take too much effort, unless you happen to be in a large city struggling to peek around skyscrapers. But what makes our star so distinct also works against it — watching from Earth, it’s impossible to discern any clear detail on its surface. The Sun’s brightness is simply too intense for us to look at it with the naked eye for an extended period of time. And in no way should you ever try observing it with optical instruments that aren’t designed for it.

It’s possible to work around this problem with the help of density filters that deflect 99.99% of all sunlight and absorb the remaining 0.01%. These are mounted on the lens itself to protect your eyesight as well as the instrument’s own. As for small-diameter binoculars and telescopes, you can use the eyepiece projection method by placing the lens in front of a white screen and projecting the Sun’s image over it. Though this approach requires no special filters, you’ll need to be vigilant with your telescope — check frequently whether it’s overheating under direct sunlight and take regular breaks.

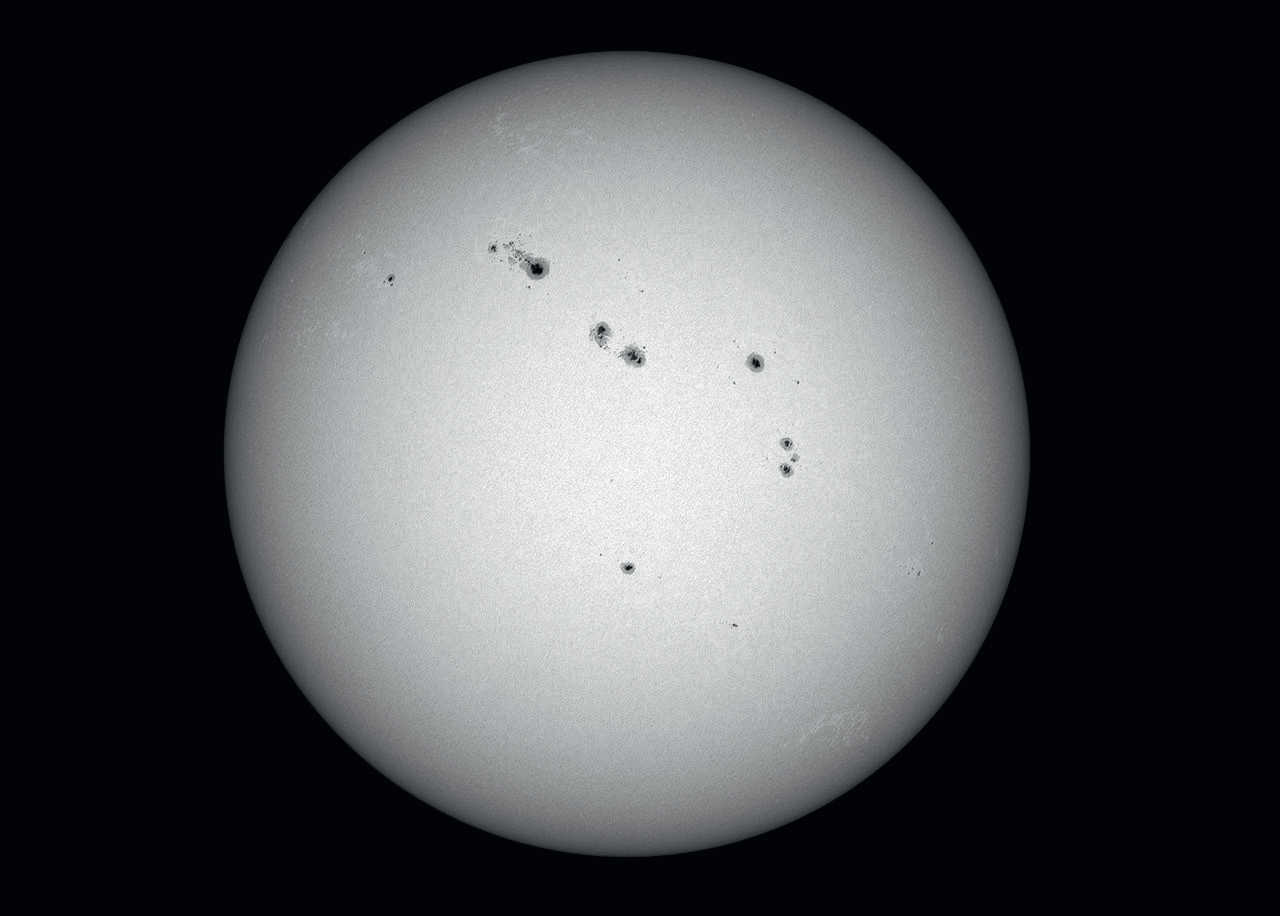

Unfortunately, inexperienced observers won’t be too impressed with the level of detail on the Sun’s surface, or its variety. During peak solar activity, the star sprouts quite a number of spots — photosphere areas where the temperature is lower relative to its surroundings. These are often accompanied by flares, which are small, bright, and more elongated. You can watch Sun activity in more detail with a special hydrogen-alpha telescope equipped with a 656.3 nanometer filter designed for the Hα emission spectrum. This way, you might even catch solar filaments — a type of prominence that occurs when hot plasma shoots thousands of miles over the Sun’s surface. Of course, these types of telescopes won’t be accessible to all astronomy lovers.

One of the most awe-inspiring celestial events is the total solar eclipse. It occurs when the Moon, while on its orbital path around Earth, shields the Sun completely. Depending on your location, this phenomenon could be an incredibly rare catch. In Ukraine and Europe, the closest upcoming total eclipse is projected for April 20, 2061.

Venus and Jupiter

The Sun and Moon are so conveniently visible, they can often be seen even in cloudy conditions. As for other inhabitants of our night sky, not only are they impossible to detect with the naked eye, but they are considerably dimmer in comparison. Simply taking a look around won’t work in this case; you will need to know the precise movement of each object to pinpoint its location on any given night.

However, two planets in the Solar System are much easier to spot by virtue of being brighter than fixed stars, such as Sirius. The first planet, Venus, is always shrouded in dense and mostly homogenous clouds, concealing its surface even from the most powerful of telescopes. What we can do, though, is track its phases, whose regular changes were first noted by Galileo.

So when is the best time to watch Venusian phases? For evening observations, it’s the period between the planet’s maximum eastern elongation and inferior conjunction with the Sun. For the mornings, the observational window is between the inferior conjunction and the greatest western elongation.

By contrast, Jupiter can put on a more effective show. Its four largest satellites, also discovered by Galileo — hence their name, Galilean — are visible through binoculars with 8-10x magnification, though to see the planet’s shape itself, you’ll only need a 20x telescope. But if the giant’s mere outline isn’t enough, you’ll need a more powerful 40x telescope, along with favorable atmospheric conditions, to admire Jupiter’s standout features — two bands of dark clouds moving north and south of the equator.

No amateur would remain indifferent after seeing such intricate details with their own eyes. Of course, sometimes they might still come away disappointed. Trouble is, they often expect to see Jupiter as it appears in professional astrophotography.

Today, you can use one of many digital planetarium apps available for both desktop and mobile users. With their help, you can easily navigate the starry sky and track any planet you want. But if you don’t have your phone at hand, you can apply this simple trick at night: if you find a bright star-like object that doesn’t seem to twinkle and matches the planet’s daily rotation speed (that is, at first glance the dot would appear stationary), then it’s almost certainly either Venus or Jupiter.

However, you will still need a telescope to tell which is which. Jupiter is easy to discern by satellites — faint star-like spots aligned in one neat row close to their parent. But if you find a tiny white-bright circle, or even half a circle, or maybe a crescent — you are definitely looking at Venus.

Saturn

Another significant difference between Venus and Jupiter is their movement. The former never strays beyond the 47° angle of separation from the Sun, while the latter passes its opposition point every 13 months, meaning Jupiter appears almost directly opposite the Sun as seen from our planet. In this configuration, Jupiter stays above the horizon throughout the night, with its visibility peaking at midnight.

The closest planet that can also be in opposition is Mars. But even with the best visibility conditions, Martian details are too undefined to make any lasting impression on a novice astronomer. The planet that has plenty of detail is Saturn, namely its glorious rings that can be seen with small 30x magnification telescopes. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is even easier to find thanks to its sheer brightness, equal to that of an 8 magnitude star.

Perhaps the biggest obstacle for finding Saturn is the planet’s noticeably weaker shine compared to Venus and Jupiter. It hardly stands out against the backdrop of fixed stars. Then again, planetarium apps can easily solve this problem.

In the coming years, Saturn watchers might hit another snag: the planet’s rings will unfold relative to Earth, turning them into a faint, fuzzy line. For a while, they will completely disappear, and even the largest telescopes won’t be able to detect them. Fortunately, this disappearing act will be temporary — Saturn’s invisible phase will occur in February and March 2025 as the planet orbits close to the Sun.

And that’s all for our list of the Solar System. There aren’t that many objects with regular visibility that are likely to impress a novice stargazer. Even the largest bodies in the Asteroid Belt look like dull stars through the telescope, while periodic comets appear as blurry, indistinct spots. Of course, comets do approach Earth from time to time to stun us with their temporary brightness, but such events are indeed incredibly rare.

Binary Stars and Star Clusters

However, outer space has plenty of its own curiosities to offer. Some of them can be seen even from large cities, so light pollution is not at all a detracting factor. First on the list are binary stars. The most famous example is Albireo (β Cygni), clearly visible for most of the year, though best observed in summer and autumn. Its two component stars, shining with a distinct yellow and blue, are separated by 35 arc seconds, so even 10x binoculars could tell them apart.

Another two pairs of binary stars appear in the spring close to the zenith — Cor Caroli (α Canum Venaticorum in the constellation Canes Venatici known as the Hunting Dogs) and Mizar (ζ Ursae Majoris). The latter is located in the middle of the handle of the famous Big Dipper asterism. Together with a slightly dimmer Alcor, Mizar forms a quadruple star system visible to the naked eye, and even 30x magnification shows a bright white satellite orbiting 15 arc seconds away from the star. What we have here is a complex system of as many as six gravitationally bound objects.

Now is the perfect time to point out that, aside from binary and multiple systems, stars also congregate in their hundreds and thousands to form larger clusters. The brightest of them are perfectly visible even through light pollution and require no large telescopes. On the contrary, sometimes these objects are better observed with wide angle binoculars. The first of these clusters are, of course, the famous Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, in the constellation Taurus. Though our naked eye is only able to detect about seven, sometimes eleven stars in the cluster, telescopic magnification shows that there are, in fact, as many as 120. This cluster is visible between late autumn and mid-spring.

Next to the Pleiades are the Hyades. Although it contain more stars, the cluster is spread over a larger area and appears much fainter.

Even more stars, over a thousand of them, can be found in the Double Cluster of h Persei and χ Persei. Viewed through a telescope, they are a truly breathtaking sight. You can also find them with the naked eye, but the sky has to be truly dark, and even then the cluster will only appear as a long faint blob. In our latitudes, the cluster never sets. In the evenings, it remains in its zenith almost through the entire winter.

If you use a small telescope for observations in Ukraine and Europe, there are other remarkable star clusters with visibly distinct components that can be worth your while. Among them are: the Beehive Cluster (M44), also known as Praesepe, in the Cancer constellation; the Wild Duck Cluster (M11) in the constellation Scutum, or the Shield; the Shoe-Buckle Cluster (M35) in Gemini; the Pyramid Cluster (M39) in Cygnus; M41 in Canis Major, near Sirius; and NGC 6633 in Ophiuchus.

All of these clusters shine bright enough to give any beginner a good idea of this class of objects. Of course, for a better experience, it’s always better to observe them in a dark sky away from big city lights.

Author: journalist Volodymyr Manko.

This article was first published in 2023 in the #1(189) issue of Universe Space Tech magazine. You can buy both the physical copy and digital version in our store.