The Rosetta project is rightly considered the most successful interplanetary mission of the European Space Agency (ESA). Within its framework, the automatic device of the same name approached the core of the periodic comet Churiumov–Herasymenko (67P/Churiumov–Herasymenko) and explored it for more than two years. The most exciting event of the mission was the first landing on a comet in the history of astronautics, accomplished by the Philae probe, which separated from Rosetta. This remarkable event took place ten years ago, on November 12, 2014.

The idea of the Rosetta mission originated back in 1986, when the European Giotto probe flew close to the core of Halley’s comet (1P/Halley) and received its clearest images. Six years later, this spacecraft visited another comet (26P/Grigg-Skjellerup), but it was not possible to photograph it. Even earlier, the American automatic ICE scout also “blindly” explored the comet Giacobini-Zinner (21P/Giacobini–Zinner) from a distance of 7800 km. This was the limit of the achievements of cometary missions as of the beginning of the new millennium.

The problem was that comets — even short-period ones — have very high speeds in the inner regions of the Solar System. Research probes launched from Earth, with the available technologies, are not able to “catch up” with them. They could approach one of them and fly past the cometary nucleus at high speed, being able to conduct its study “up close” for a very short time. Of course, it is not worth hoping for a large amount of scientific information in such conditions.

But if the spacecraft is additionally accelerated in the gravitational fields of large planets, it can be transferred to an orbit close to the comet, after which it can approach the “tailed star”, equalize its speed with it and get enough time for its detailed study. That was what the Rosetta probe was supposed to do. It got its name from the “Rosetta Stone” found in 1799 in Egypt. There were three identical texts on the stone slab, executed in two ancient Egyptian writing methods and the ancient Greek alphabet. This helped historians decipher many documents from distant eras. Similarly, scientists hoped that Rosetta would find clues about the history of our Solar System in cometary matter, which didn’t change much over the past 4 billion years.

Initially, the probe was going to be sent to comet Wirtanen (46P/Wirtanen), and it was supposed to launch on January 12, 2003. But in December 2002, the Ariane 5 ECA rocket exploded, and all flights of this carrier were suspended for almost a year. During that time, the positions of the objects of the Solar System had changed significantly, and the mission group had to look for a new target for the spacecraft. It became 67P/Churiumov–Herasymenko, a comet discovered in 1969 by Klym Churiumov and Svitlana Herasymenko, employees of the Kyiv University Observatory.

The new trajectory of the probe included three gravity maneuvers near the Earth and one in the sphere of gravity of Mars, completed on February 25, 2007 (by the way, the maneuver took place on this planet for the first time in the history of cosmonautics). Rosetta received electricity for on-board equipment from solar panels and became the first spacecraft with such a power source to reach the orbit of Jupiter. All its predecessors used radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) for power supply. On the way to the main goal, it visited two asteroids of the Main Belt: on September 5, 2008 — the 5-kilometer Steins (2867 Šteins), on July 10, 2010 — the 120-kilometer Lutetia (21 Lutetia). Interestingly, Lutetia is the ancient name of the city of Paris, where ESA headquarters is located.

Finally, in August 2014, Rosetta arrived in the vicinity of the cometary nucleus. Although it weighs almost 10 billion tons, its mass is distributed according to a strange irregular shape. According to the first letters of the names of the discoverers, it was jokingly called “ChuHeZavr”. Therefore, it turned out to be very difficult to get into a stable orbit around it. This was also hampered by emissions of matter from the comet, which increased as it approached perihelion. The spacecraft had to constantly adjust its trajectory and simultaneously conduct scientific research. One of the first surprises was the presence of a magnetic field at the core, oscillating at a frequency of 40-50 MHz.

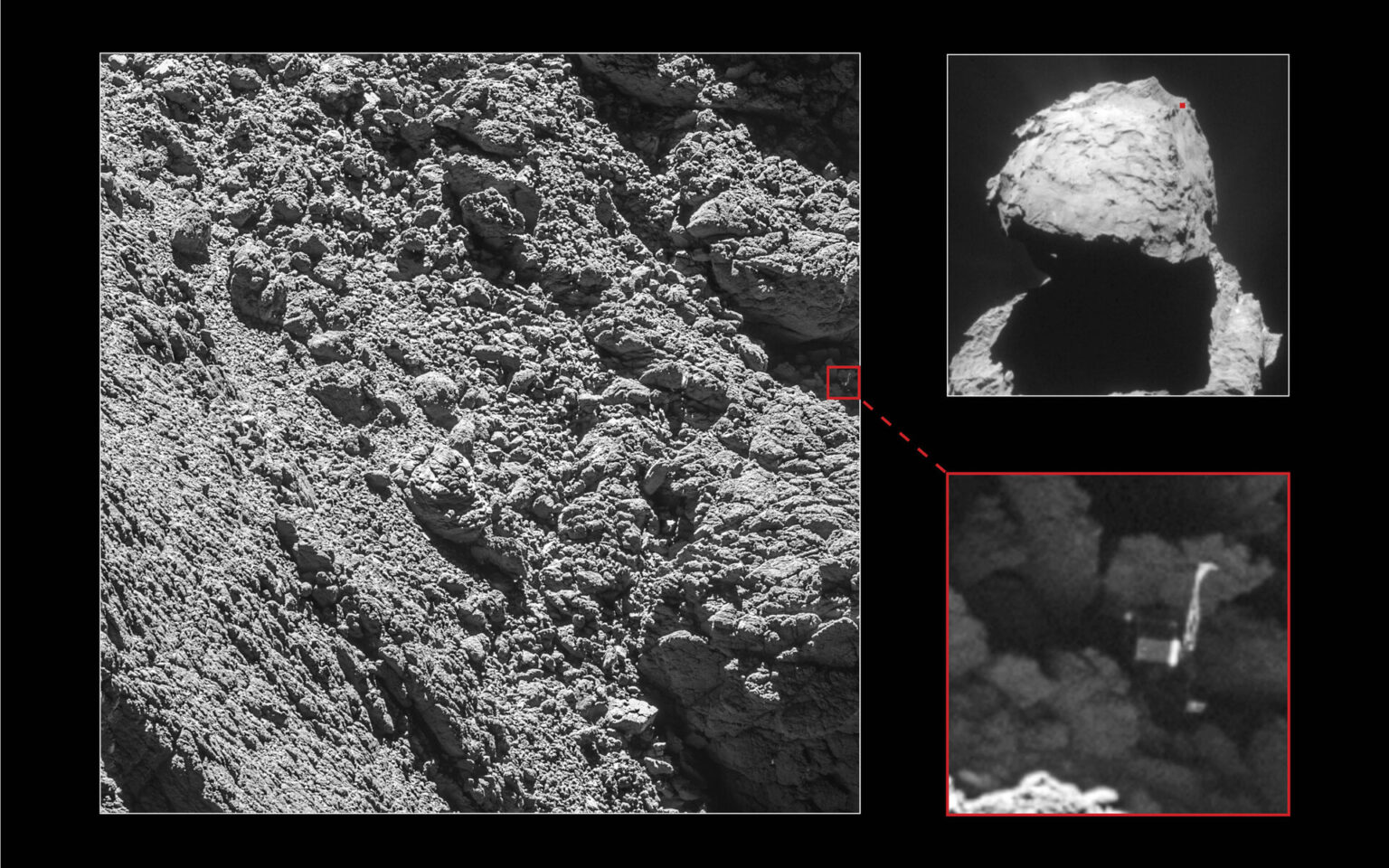

On November 12, 2014, the Philae lander separated from the main probe and moved towards the cometary core to carry out its research. Unfortunately, during 10 years of space travel, the instruments that were supposed to fix it on the surface failed. In low gravity conditions, the 100-kilogram module bounced off the core twice and eventually “got stuck” in a fairly deep gorge, where lighting conditions did not allow it to fully use solar panels. Therefore, it carried out a scientific program until the charge of the onboard batteries ran out. Later, it was possible to establish contact with it for a short time and “pull out” part of the received data.

After that, for almost two more years, Rosetta conducted research on the comet and outer space in its vicinity. The number of images of the core from various distances exceeded one hundred thousand. Many carbon and nitrogen compounds have been found in the composition of cometary matter, some of which are considered to be the “building blocks” of molecules important for terrestrial life. A special part of the mission was a series of comics for children, depicting its most important stages in an accessible artistic form. All this time, Klym Churiumov wrote articles and participated in TV programs where he talked about the results of studying the “tailed star” of his name, commenting on them as a specialist.

In mid-2016, ESA decided to end the mission by purposefully colliding the Rosetta probe with the comet’s nucleus. This operation was carried out on September 30 of the same year. After the fall of the spacecraft, contact with it was lost. The last photos of the core surface that it managed to transmit were taken from a distance of 17-21 m and had a resolution of less than 10 cm per pixel. And two weeks later, on October 15, 2016, the world astronomical community found out about the death of Klym Churiumov.

Since that time, mankind’s messengers have not automatically visited any comet anymore, and no specialized comet mission has yet reached the design stage.

Earlier we explained why the visible brightness of a comet was so difficult to predict.

Follow us on Twitter to get the most interesting space news in time

https://twitter.comne/ust_magazine