The activity of the first powerful spring meteor shower, the Lyrids, occurs in the second half of April. In early May, the Earth passes through the dust plume of Halley’s Comet, which is observed as the η-Aquarid shower. And then our planet plunges into a relatively sparse meteor swarm, the radiant of which is also located in the constellation Lyra, not far from its star η (eta). That is why it is called the η-Lyriids. It is associated with a very interesting comet that came as a great surprise to astronomers in the spring of 1983.

…On 25 January 1983, the IRAS satellite, the first large space telescope to observe the sky in the infrared range, was launched into Earth orbit. At the end of April of that year, several British astronomers, looking at the images transmitted by it, noticed a rather large object whose position had changed significantly between the two exposures. The scientists quickly recognised it as a comet. If they had acted according to the script of the film Don’t Look Up, humanity would not have learned about it for a long time. Instead, they did exactly what astronomers are supposed to do in such cases — they sent information about the new celestial body to the International Bureau of Astronomical Telegrams (IBAT) in Cambridge, USA. Moreover, they sent requests to several ground-based observatories that could have taken pictures of the nearby sky at that time, and on 27 April they received confirmation of their discovery from the Swedish Kvistaberg Observatory.

While the IBAT staff were registering messages and organising their own mailing list, the new comet continued to approach the Earth and became brighter. On 3 May, it was independently spotted by two astronomy enthusiasts, the Englishman George Alcock and the Japanese Genichi Araki. They also sent their information to Cambridge, after which the “tailed guest” finally received its full name and official designation. It is now known as C/1983 H1 (IRAS-Araki-Alcock). The very next day, it was already visible to the naked eye.

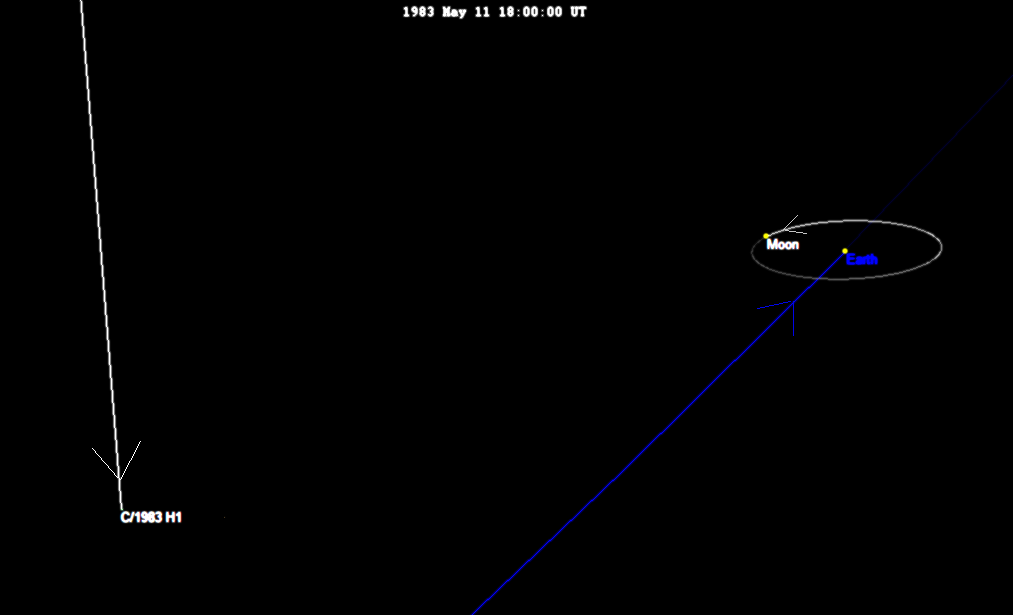

A growing number of positional observations made it possible to determine the comet’s orbit quite accurately. It turned out that it passes at a distance of less than 900 thousand km from the Earth’s, and on 11 May, C/1983 H1 and the Earth will be almost simultaneously near the point of closest approach. However, the comet was still a little “late”, so the minimum distance to it on that day was 0.0312 AU (4.67 million km). Still, for several days it was an unforgettable sight. In the dark sky outside of large cities, it was observable as a large, bright, elongated “jellyfish”, whose movement against the background of the stars could be seen with the naked eye. Many people who were not familiar with astronomy reported seeing UFOs. Fortunately, the press found out about the unusual celestial body rather late, and there was no Internet back then, so there were no frightening newspaper headlines about the “imminent collision of the comet with the Earth”.

Now we know that the period of the IRAS-Araki-Alcock’s orbit around the Sun is 970 years. It has been present in its current orbit for quite a long time, so it could have left a noticeable “meteor trail”, but the concentration of solid particles in the nucleus of this comet is quite low, and the number of meteors per unit of space, even in the place of the closest approach of the comet and Earth’s orbits, is relatively small. At the maximum of activity, which this year falls on 11 May, the so-called hourly zenith number of η-Lyrids will not exceed 5.

The passage of C/1983 H1 near the Earth on 11 May 1983 was the closest known approach to a comet in the previous two centuries. Only the comet Lexell (D/1770 L1 Lexell) came closer to us on 1 July 1770 — on that day, the distance to it was only 2.2 million km, which is only six times the average radius of the lunar orbit.

Earlier, we wrote about how to see the periodic comet Olbers, which is currently approaching the Sun.