On February 18, 1930, astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. For many years, it remained a faint dot in telescope images. We could only wonder what this distant and cold world was really like.

That all changed when the New Horizons spacecraft visited Pluto in 2015. The images it transmitted showed an object completely different from what scientists expected to see: a world with blue sky, icy mountains, methane snow, and, of course, the famous heart.

On the occasion of Pluto’s discovery’s 95th anniversary, the editors of Universe Space Tech have compiled a selection of its best images. These images demonstrate Pluto’s beauty and make us wonder once again whether astronomers were wrong to exclude Pluto from the list of planets.

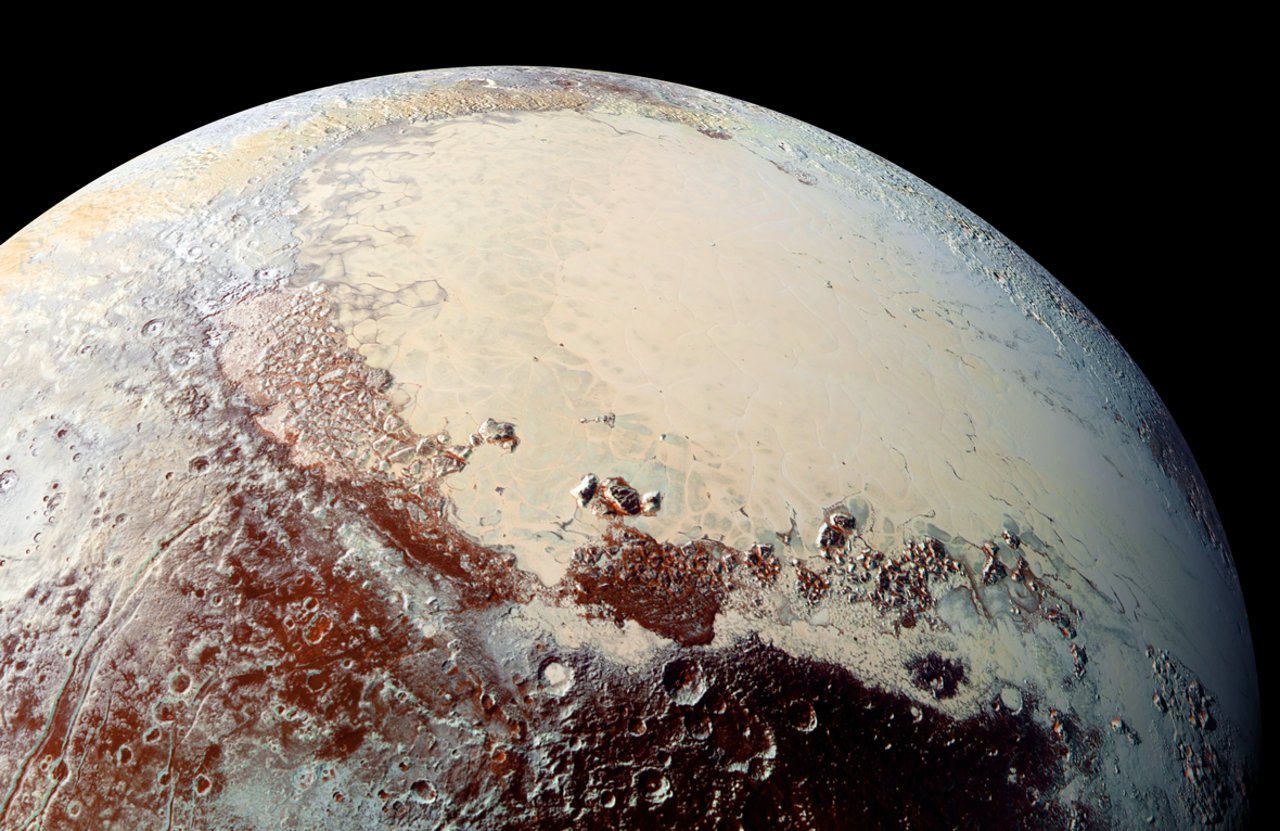

Pluto in its natural colors

If we could take a trip to Pluto, the following picture would be revealed to us. This is how the former ninth planet looks in natural colors. The distance of the image was 35,000 kilometers, which is comparable to the orbital altitude of geostationary satellites.

Pluto’s heart

The most famous object on Pluto is the famous “heart”, a characteristically shaped region called the Tombaugh Regio. Its western part, known as the Sputnik Planitia, is one of the most amazing formations in the entire Solar System. It is a smooth and virtually crater-free plain 1500 kilometers in diameter, covered in nitrogen ice. It is assumed that this whole region is a giant vortex that is subsequently filled with nitrogen.

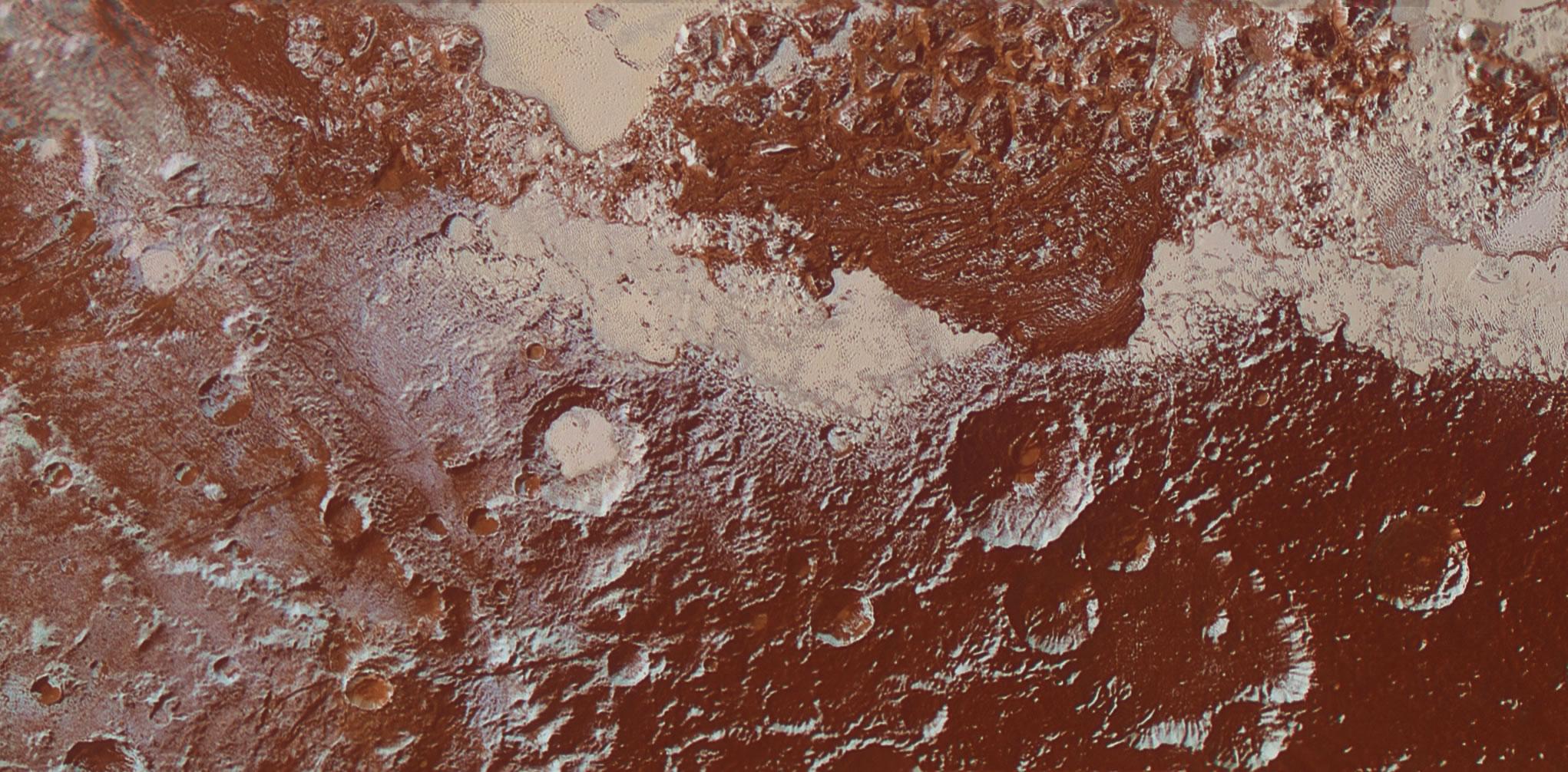

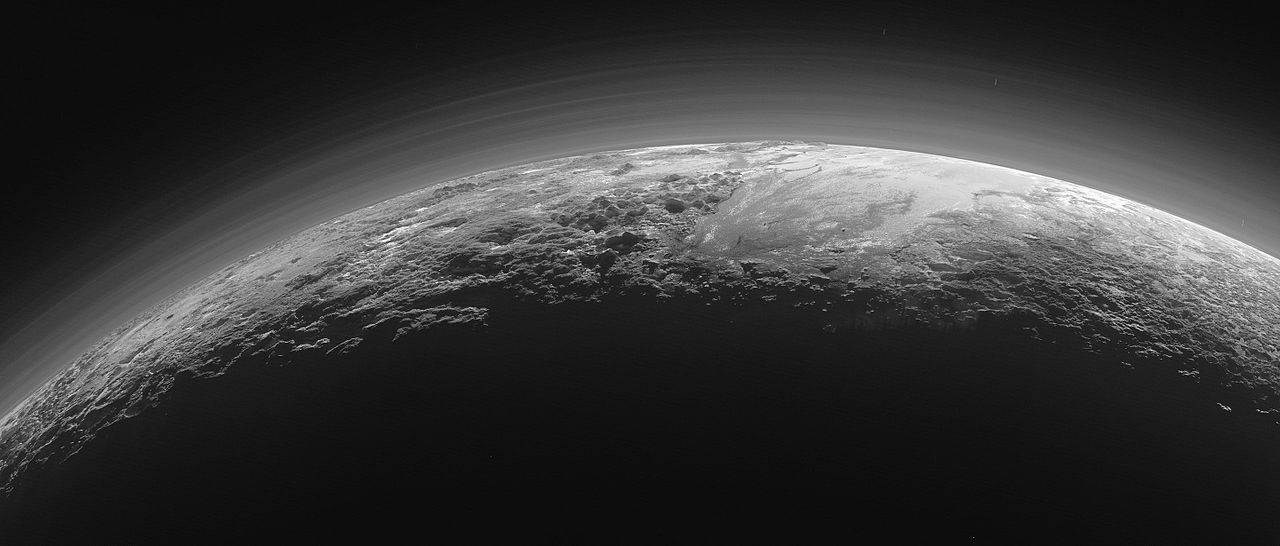

Pluto’s “coast”

This image shows a peculiar “coast” – the boundary between the Sputnik Planitia (on the right) and the surrounding older mountains (on the left), which are composed of water ice. From time to time, ice blocks break off from them, which, like icebergs, then begin to drift across the vast sea of nitrogen.

Source: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

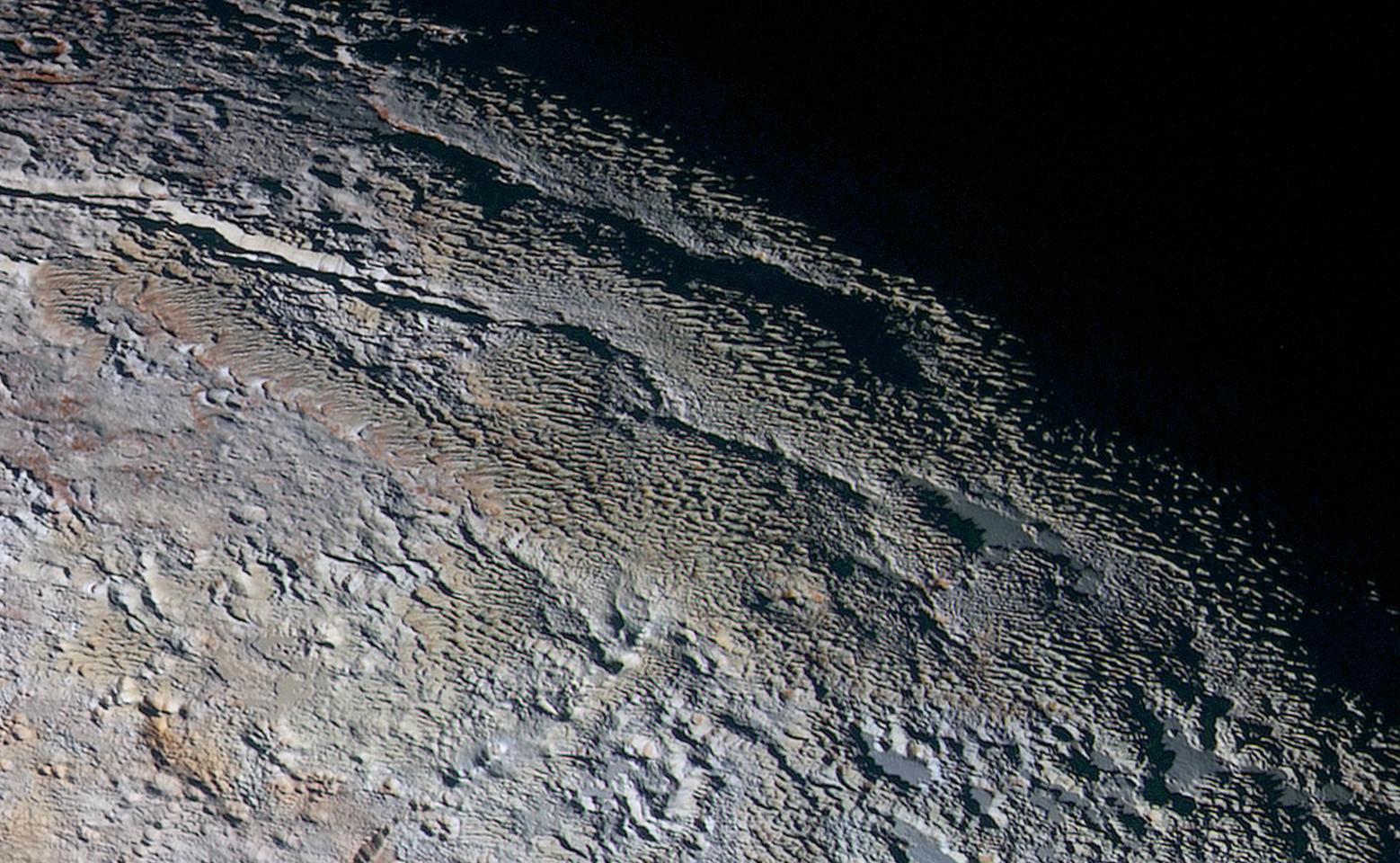

Pluto’s “snakeskin”

The Sputnik Planitia is not the only geologic landmark on Pluto. On its surface, there are also areas covered with jagged formations that look like needles. Their height can reach 500 meters, and they are usually arranged in rows with an interval of 3-5 km. Astronomers figuratively compare such regions with snakeskin.

Methane snow and organics

Like on Earth, Pluto also has snow caps on top of some of its mountains and craters. Only they do not consist of ice, but of methane frozen out of the atmosphere. In turn, there is no snow at the bottom of the craters. They are covered with a mixture of complex organic molecules called tholins.

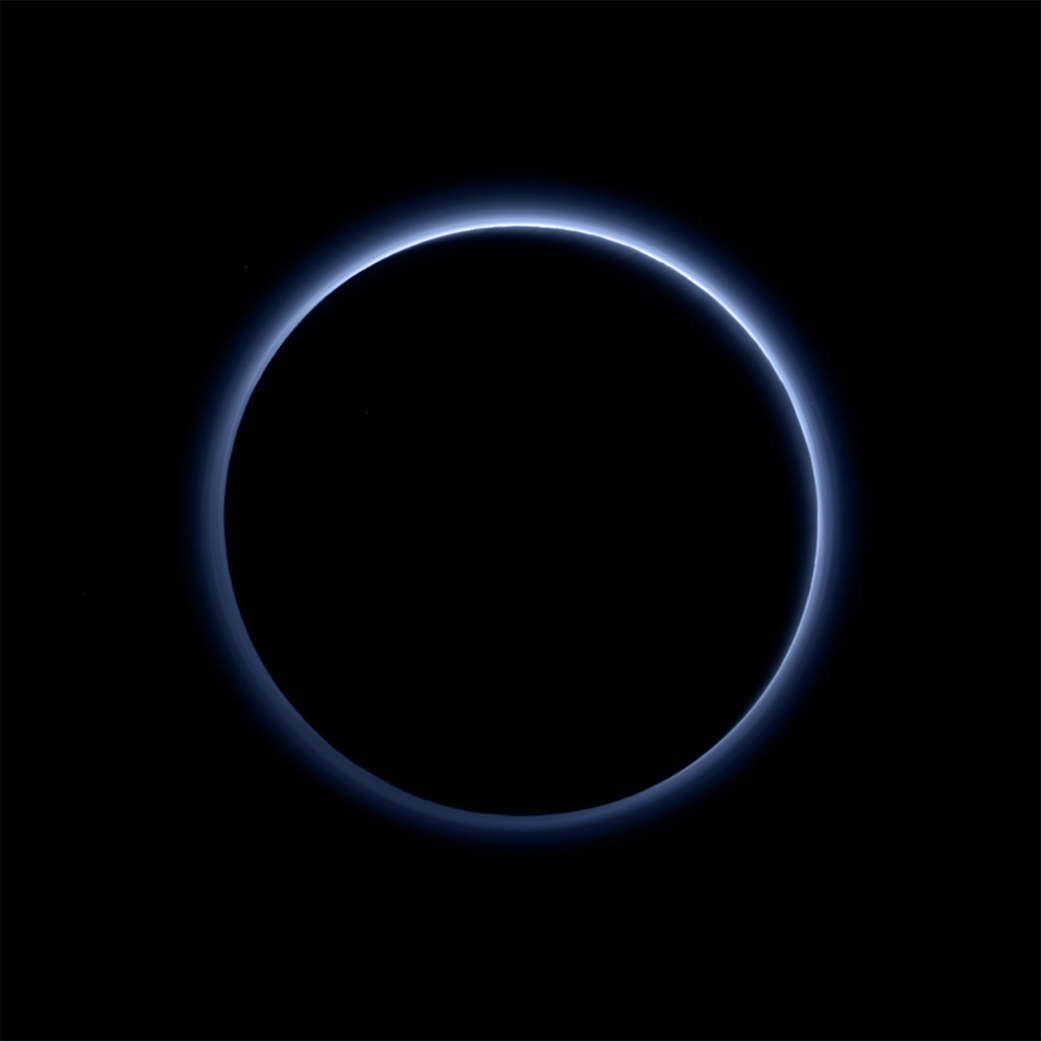

Pluto’s blue sky

Although Pluto’s atmosphere is extremely thin, it has a complex structure and consists of many layers of hydrocarbon haze, which is blue. It can be seen in the New Horizons image, taken at the moment when the dwarf planet covered the Sun. Thus, Pluto is the second body in the solar system after Earth, which has a blue sky.

The predawn fog on Pluto

Like on Earth, Pluto has predawn fog. It can be seen in the image taken by New Horizons from a distance of 18,000 km, which shows the boundary between the day and night side of the dwarf planet.

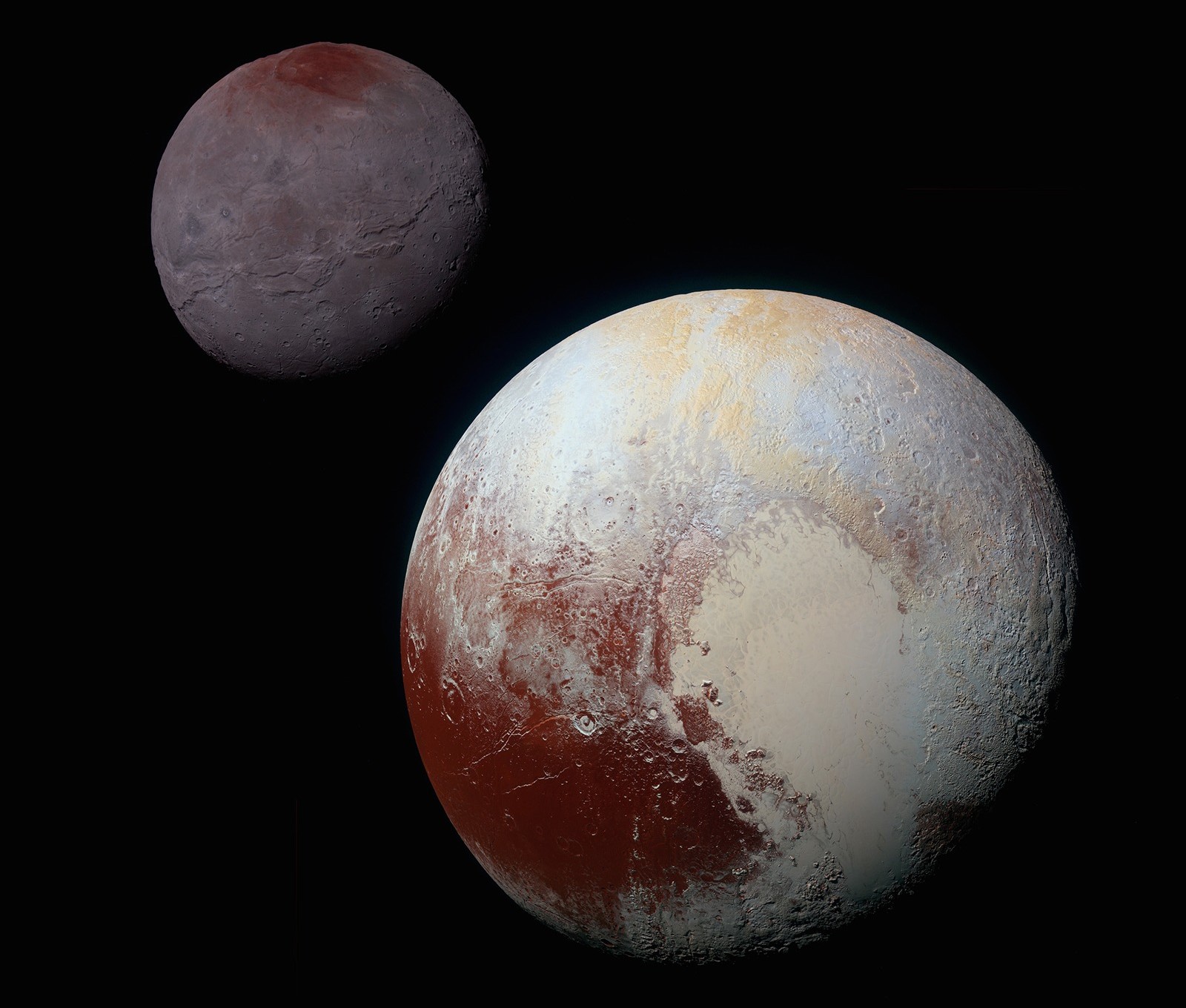

Pluto and Charon

Pluto has quite a large family of satellites. The largest of these is Charon, whose diameter is only twice as large and whose mass is eight times smaller than Pluto’s. Because of this, their center of mass is outside of Pluto. The dwarf planet and its companion orbit around a common center of gravity and are always turned toward each other on the same side. In the days when Pluto was still considered a planet, some astronomers suggested that the pair be considered a double planetary system.

The dead ocean of Charon

If you look at a portrait of Charon, you will notice a system of giant faults girdling its equator. Astronomers believe they were formed when the satellite’s subsurface ocean froze. The water turned to ice, causing the interior to expand and the crust of Charon to crack.