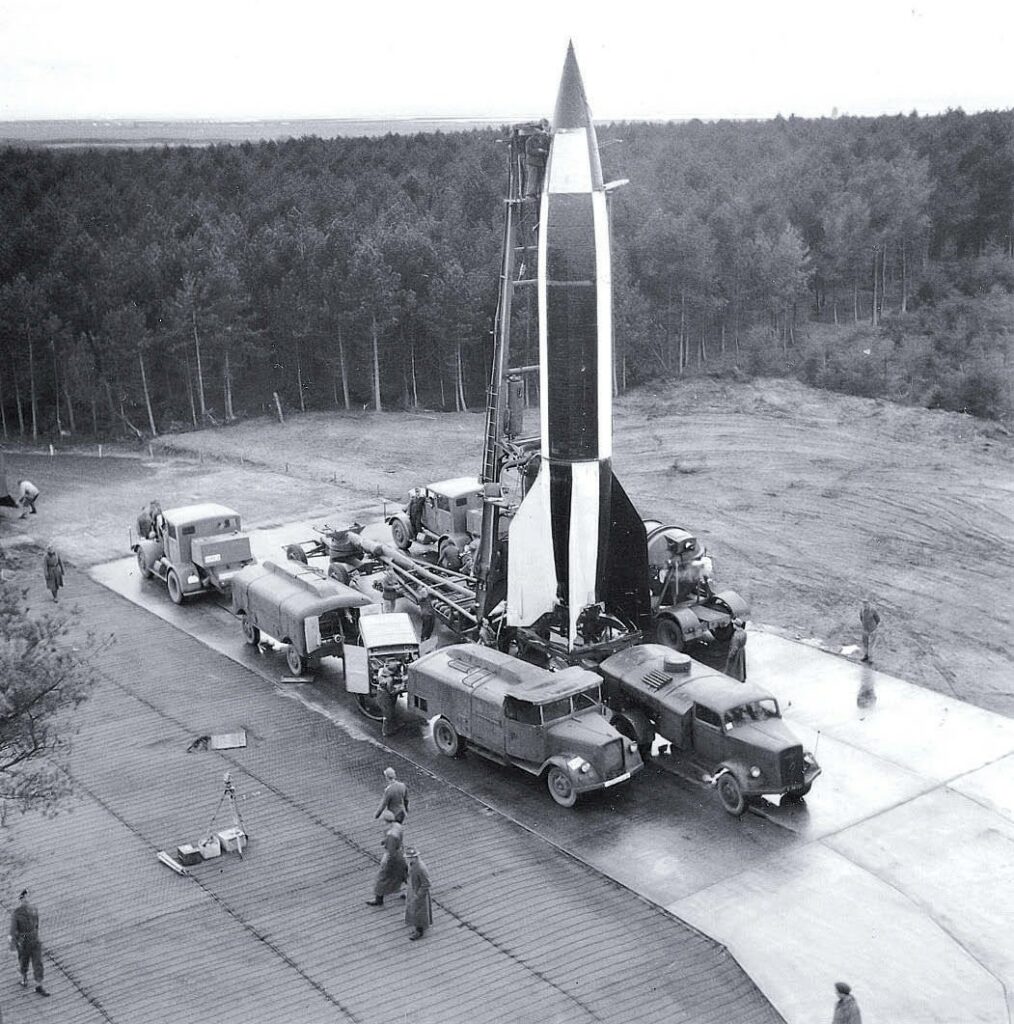

In September 1944, London became the first city in the world to be hit by V-2 combat ballistic missiles. In total, until March 27, 1945, the British Isles survived 1,402 missile attacks. Nazi Germany fired more rockets only at Belgium (1,664).

…On a cold autumn day in October 1945, the German launch squads were routinely preparing for the launch of another V-2. The launch was successful; the rocket rose into the sky and disappeared into the distance. The soldiers and officers who were there rushed to greet each other. Among them were those who had never seen a rocket launch before — English rocket engineers. And the launch was carried out as part of Backfire operation, which is considered the starting point of the British space program.

Paperclip operation

Shortly before the end of the World War II, a kind of “battle” between the USA and the USSR unfolded on the territory of Germany — the two future superpowers tried to get as many trophies and specialists related to German rocket technology as possible. However, few people know that the third winning country — Great Britain — was also involved in this “competition”. The British perfectly understood what opportunities the new age of rocketry would open up to them. Unfortunately, their intentions were seriously limited by the actions of the Americans, who launched their Paperclip operation. They wanted to capture as much as possible of what was left of Germany’s rocket industry, trying to “keep up” with their Soviet competitors. They managed to get the famous Werner von Braun to the USA, along with a large collection of technical documentation that he saved from destruction when the Nazi state ceased to exist. Many of these documents were actually “borrowed” from the British occupation zone.

As a result, the British did not get neither rockets nor qualified rocket engineers. But they were absolutely correct in deciding that the people who launched the V-2 every day were also well-informed about the practical capabilities of German rocket technology. That’s how the idea of conducting their own operation arose.

On the eve of the “battle for space”

A search was organized in prisoner of war camps for soldiers who serviced the V-2. The search team Altenwalde was formed of them. Now, the people who launched the world’s first ballistic missile attack had to work with those they were shooting at.

During the Backfire operation, the British gained the knowledge and experience necessary to participate in the rocket and space races. Moreover, they became leaders in the creation of rockets running on hydrogen peroxide. Having such a base, multiplied by British ingenuity, it was possible to try to compete with the world’s rocket giants.

The British were worried not so much about prestige, but about the increasingly difficult military situation. An “iron curtain” was falling over a divided Europe, von Braun and Korolev (who witnessed the Backfire launches) were creating new missile weapons for the superpowers on different costs of the ocean, and Britain, under these conditions, sought to develop its own missile industry.

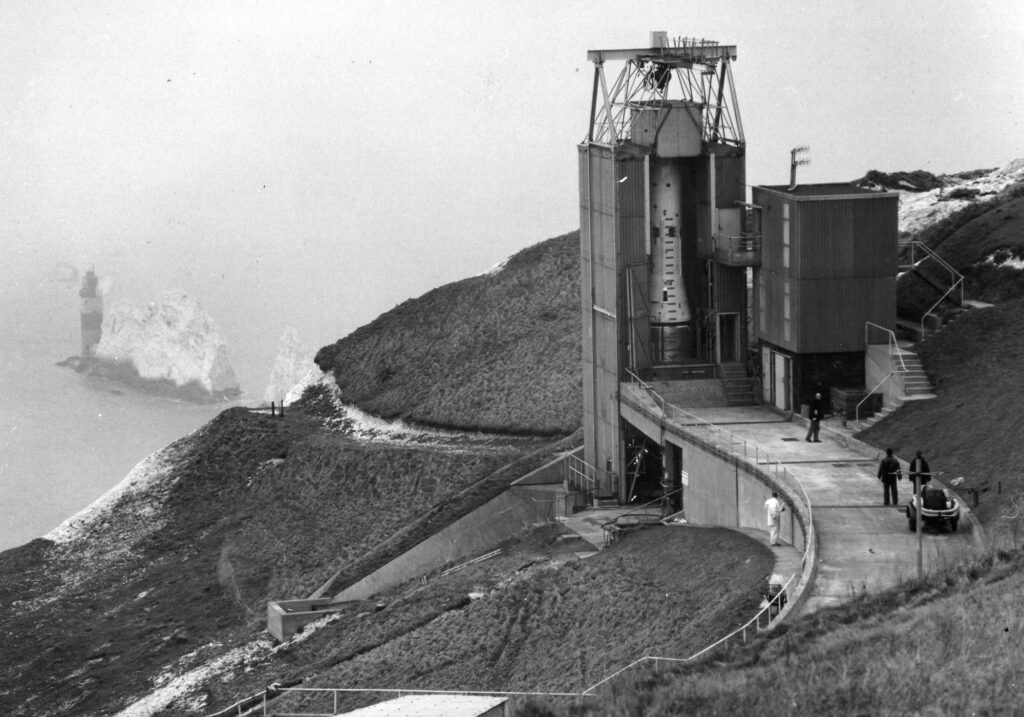

The first success came in 1953, when the Blue Streak medium-range silo-based ballistic missile was created. It looked quite promising, so soon Black Knight missile appeared. This rocket was already able to reach Earth orbit. Its tests were conducted in a bunker complex on the Isle of Wight with a wonderful view of the Needles stack. It also proved to be quite reliable, becoming an important stage in the British missile program.

Thus, the UK now had all the key components to launch a national satellite into orbit with its own carrier. However, first the choice was made in favor of launching the spacecraft (named Ariel) using a cheaper American rocket. The Blue Streaks and Black Knights were replaced by Black Arrow, the first British launch vehicle potentially capable of orbital launch.

One step to orbit

The three-stage Black Arrow was a masterpiece of engineering on a limited budget. Scientists and engineers were determined to prove that a large maritime power is quite capable of conquering outer space on its own. On the basis of earlier British rockets, they created a carrier that, when launched from the “correct” place, could take the payload into polar orbit. And the design offices have already been designing the Black Prince — an even more advanced rocket capable of launching geostationary satellites…

By 1968, the plans were ready for implementation, but the lack of money became an obstacle. For reasons not entirely clear, the Treasury took a dislike to the British rocketeers, ruthlessly cutting their budgets and closely controlling their spending. It was difficult to work under such conditions. The allocated funds allowed building only five t rockets and only two satellites. In fact, now the experts had no right to make a mistake. They almost literally had only one shot left.

The joint British-Australian Woomera test site was chosen as the launch site, where military and civilian rocket engineers worked together. In fact, this choice was not easy either — initially it was proposed to launch a satellite from the British Isles with the launch trajectory over the North Sea (in case of the carrier’s failure). However, precisely at this time and precisely in this water area, oil production began to develop rapidly, and it became clear that no matter how improbable it seemed that a faulty rocket would hit an oil platform, it was still better to completely exclude such a possibility. Fortunately, there was enough free space for launch activities in Australia, and Woomera became the site of many launches for various countries for a long time.

By 1969, the first of five rockets was ready. Financing were becoming even more difficult, and the Treasury again began to reassess the future of the project.

Getting ever worse

The engineering team decided not to back down. On June 27, 1969, Black Arrow was installed on the starting position. Its launch, which took place the next day, was unsuccessful.

Even before the carrier left the launcher, a failure occurred in its electrical system. This caused the pair of first-stage combustion chambers to shift, so that immediately after the start of ascent, the Black Arrow began to spin uncontrollably. In a minute, the rise was replaced by a fall, and the rocket had to be detonated by the launch operator.

In principle, everything was not so terrible. The cause of the failure was quickly discovered, and the team prepared for the next launch (it took place on March 4, 1970). The second Black Arrow did irreproachably. It`s task was not to reach orbit — it was only about testing the engines of the two lower stages.

During the third launch, scheduled for September 2, the first test of the engine of the third, last stage of the carrier was supposed to take place. If it had completed its mission, it would have put one of the two precious satellites (named Orba) into orbit. But the rocketeers were let down by the second stage, which did not work out the proper time.

The chances of success have decreased. And then disaster struck. On July 29, the Minister of State for Trade and Industry, Frederick Corfield, announced in the House of Commons the official closure of the British national satellite launch program.

The last hope

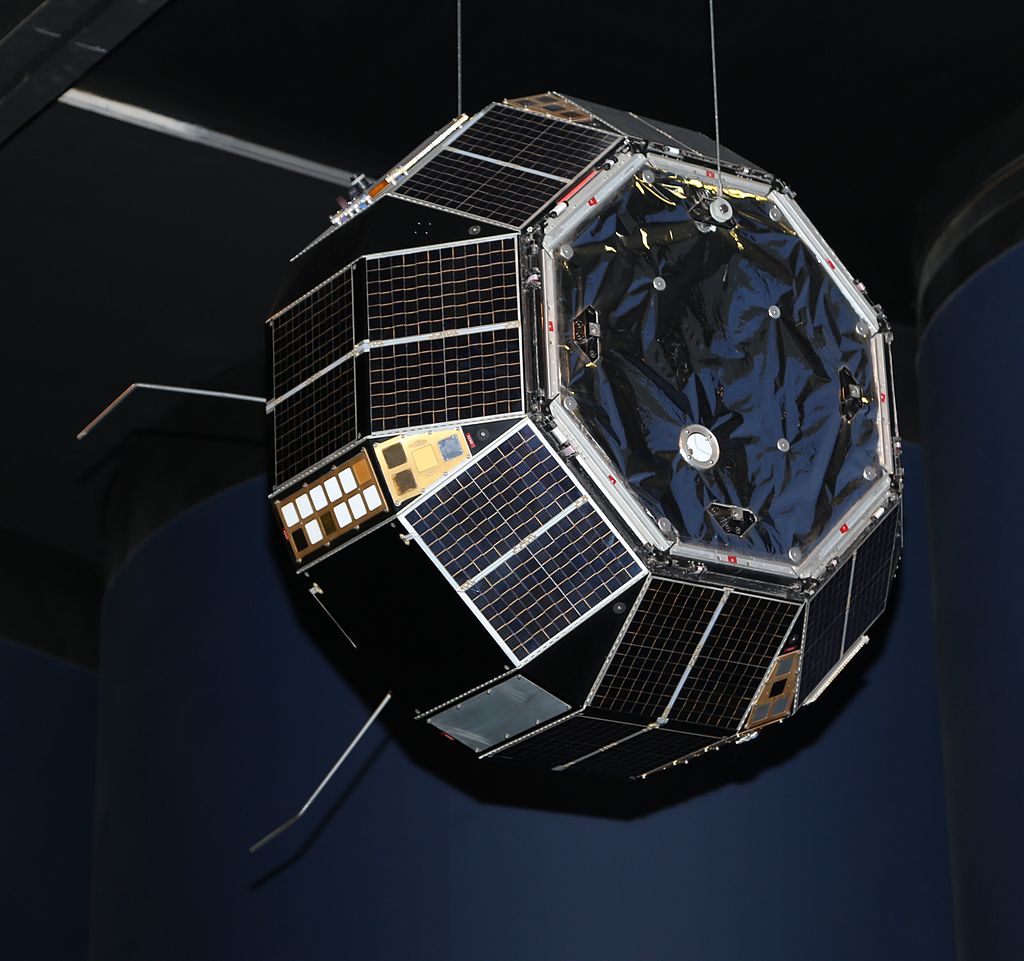

When news of the project’s cancellation came, the fourth Black Arrow was already on its way to Australia. Using it, they were going to launch the last of the available satellites — a simple sound-reproducing device with the working name Puck (the British rocket engineers gave all satellites the names of characters from Shakespeare’s works).

Scientists convincingly explained to Treasury bureaucrats that it would be chipper to launch the rocket than to return it to its port of shipment. The argument was convincing. Black Arrow team got their last chance. The start was scheduled for October 27, but weather conditions did not allow it to be carried out that day.

On October 28, 1971, every British rocket engineer seemed to be watching what was happening at Woomera. The countdown has started again. The fourth Black Arrow, the last to receive permission to fly, was standing on the site. At the top of its third stage was the last of the satellites, renamed Prospero with a tint of irony (honoring the magician from Shakespeare’s The Tempest who drowned his magical books and gave up witchcraft forever).

At 3:50 a.m. GMT, the first “peroxide” stage of the carrier was fired, which probably would delight the German soldiers firing the V-2. Ten seconds later, Black Arrow began to rise from the cloud of superheated steam. Three minutes later, the first stage separated perfectly and the engines of the second turned on exactly on schedule. Finally, they also fell silent, having successfully passed the baton to the third degree. Everything went according to plan.

And yet, literally in the last seconds, something went wrong. As Prospero separated from the third stage, its engines were still running, and it continued to accelerate, colliding with the satellite.

There was silence in the control center. Everyone sat waiting for what would happen next. Finally, after several long minutes, Prospero’s radio-transmission reached Earth.

Instead of an epilogue

The last Black Arrow never flew — it is now on display at the Science Museum in London. The scientists and engineers involved in the launch of the British satellite were not greeted as heroes. By the time they returned home, many had simply been fired. Some of the participants of the historic launch found a place in the US space program, some — in the industry at home.

And lonely Prospero is still orbiting around the Earth. Its tape recorder broke a few years after launch, but the solar panels still function. For many years, the tracking station of the British air force at Lasham used to contact the satellite unofficially on its ‘birthday’, but the facility was shut down 20 years ago and an attempt by staff at the University College London to ‘wake up’ the craft to mark its 40th birthday was unsuccessful. It turned out that with the closure of the tracking station, all activation codes were lost and could not be reproduced. Now all we have to do is trace Prospero’s path among the stars by Internet. In the COSPAR catalog it has the designation 1971-093A. The only stellar messenger of the “Queen of the Seas” will enter the Earth’s atmosphere in about 2070.