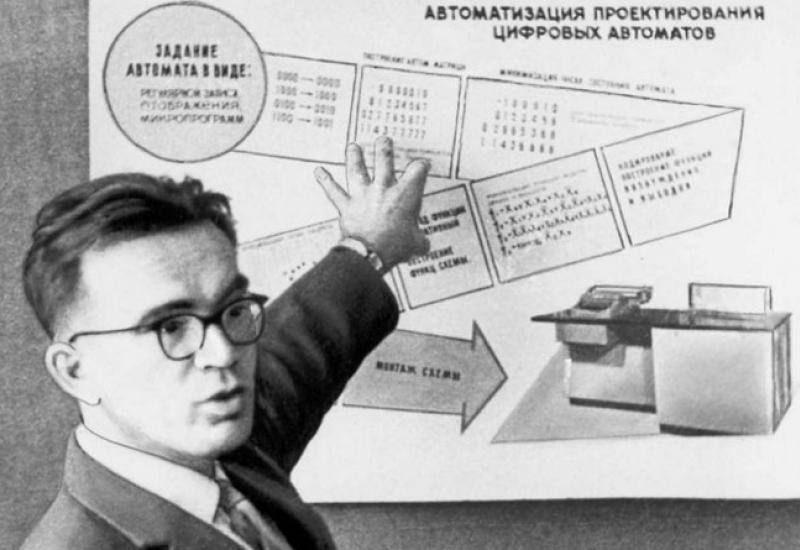

Can paper bureaucracy be completely eliminated so that all state functions provided solely in electronic form? This question sounds absolutely modern, but it was first posed by the founder of the Institute of Cybernetics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Viktor Glushkov. As early as 1962, he proposed creating the world’s first computer network that would connect tens of thousands of machines.

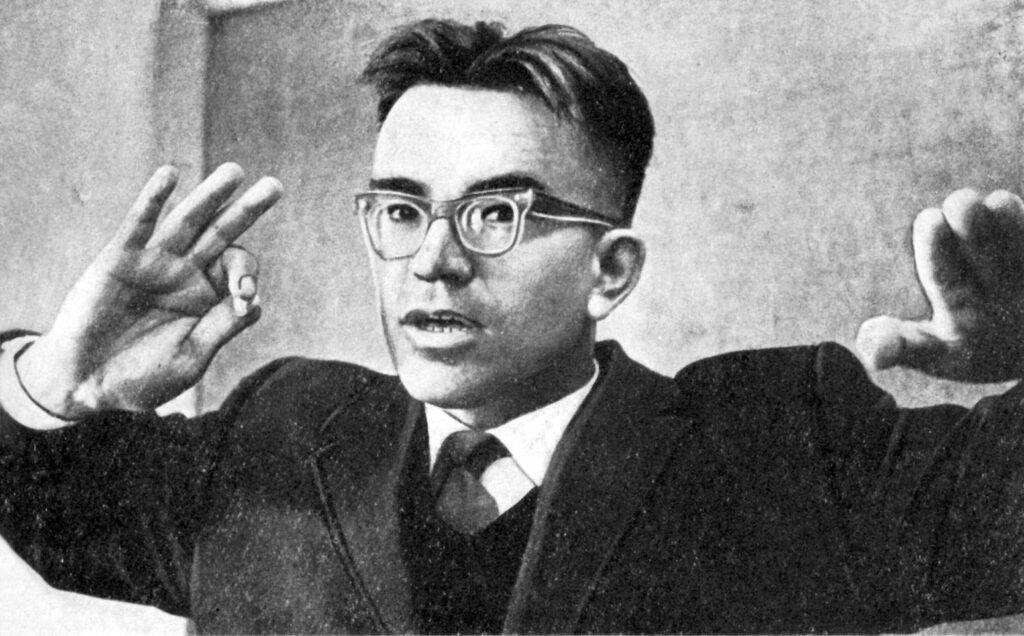

A Mathematician Who Became a Cyberneticist

Exactly 100 years ago, on August 24, 1923, in Rostov-on-Don, a person was born into a family of Ukrainian Donbas immigrants who was destined to turn Kyiv into one of the centers of global computer science even as the field was just emerging. From early childhood, he showed remarkable aptitude for mathematics and by the 8th grade, he knew not only what was taught in school but also much of what was taught at the university.

However, in his later years of school, he became fascinated by physics. This was during the Second World War. Somehow, he managed to survive the war and enroll in a local university. According to Viktor himself he wouldn’t have been admitted to a Moscow university, despite his abilities.

In the USSR, the nuclear program was in full swing, and after graduating from the university, Glushkov was sent to the Urals, where he could have stayed for life in one of the closed cities. However, due to a Soviet bureaucratic glitch, he ended up without money in a place where nobody was waiting for him.

Glushkov found a job as a teacher at a school and soon made his way to Moscow, where he permanently left behind his physics career and delved into mathematics. In 1951, at the age of only 28, he obtained his candidate of sciences degree, and at 32, his doctorate. Despite working on purely mathematical issues, he didn’t become a luminary of Moscow mathematics. Instead, the scientist changed his life path once again and went to Kyiv, where they were among the first in the Soviet Union to start building computers.

Dawn of Computing Technology

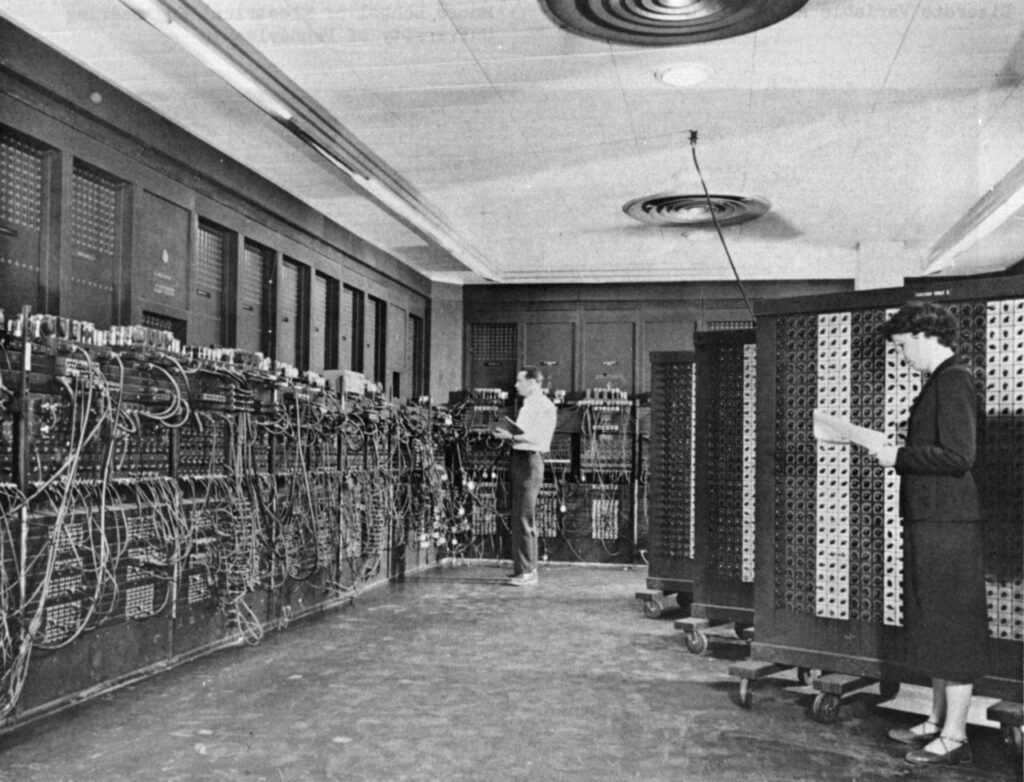

For those familiar only with the current state of information technology, it’s quite difficult to imagine what it was like when it was just beginning. Nowadays, we most often deal with smartphones that fit in our pockets. Tablets are considered slightly bulkier, and laptops are used even less frequently, and personal computers are a rare sight.

In 1956, when Viktor Glushkov came to Kyiv to lead the laboratory of computing technology, a typical electronic computing machine was a set of huge “wardrobes” that filled an entire room and performed dozens or hundreds of operations per second.

Due to the use of thousands of electronic tubes, each of considerable size, these machines were of giant proportions. Even this was a huge step forward, as just 10-15 years before, computers were still mechanical, even bulkier, and slower.

Looking at what Glushkov started with, it would be difficult to recognize a computer in that set of devices. The matter is that the computers of that time didn’t have monitors and information input was done using punch cards with holes.

However, it was already clear back then that these machines could solve problems beyond human capabilities. During WWII, the British Colossus computer was able to decipher the German Lorenz cipher. The USSR and the USA had just started the nuclear race, which required a large number of calculations, and they were also preparing for space flights, which required even more.

This is why computers were developing at an incredible pace. Tubes were already outdated. They were replaced by much more compact semiconductor elements — transistors. One square meter of a circuit board could contain hundreds of times more transistors than electric lamps.

Computers by Viktor Glushkov

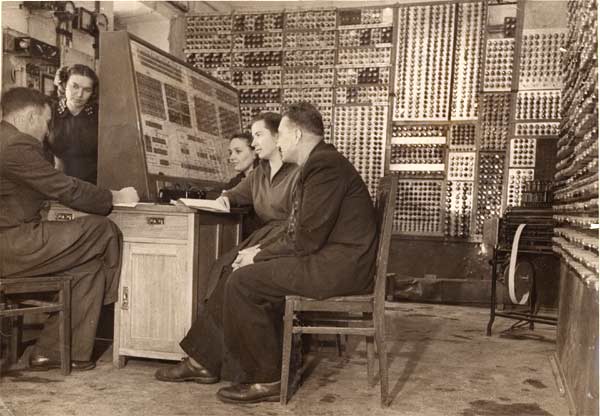

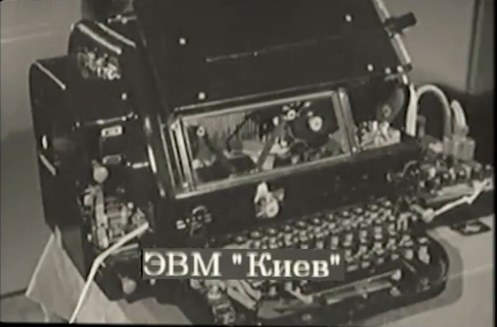

The work in the capital of the Ukrainian SSR was focused on one such machine when Glushkov arrived there. It was named after its location — Kyiv. Like all computers of that time, it consisted of a set of wardrobes with equipment that filled an entire room. However, its speed was already quite impressive —15,000 operations per second. Additionally, the machine had a library of programs stored on magnetic drums.

It’s important to note that programming at that time was vastly different from what modern computer scientists are accustomed to. There were no text editors yet. Electronic computing machines only responded to sequences of numerical codes, understandable only to mathematicians. The operational memory of the Kyiv machine could only hold 1024 such codes.

However, it was on “Kyiv” that one of the world’s first high-level programming languages that we are familiar with today was applied. It was called “Address Programming Language” and was developed by the prominent cybernetician Katerina Yushchenko.

Despite these relatively modest specifications, Viktor Glushkov managed to use the “Kyiv” computer to solve a number of extremely complex problems. A second copy of the machine was installed at the center of nuclear research in the town of Dubno. And on the original machine, which remained in the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, some of the world’s first experiments in recognizing printed text and simple shapes in the form of geometric figures were carried out. However, performing such operations on a computer became a common practice only in the 1990s.

In 1960, Viktor Glushkov conducted a series of experiments with remote control using the Kyiv computer. However, this control was not over a model airplane or a toy car; it was over a steel melting plant located 500 km away.

Yet, Glushkov didn’t limit himself to just Kyiv. The next computer developed under his leadership was the Dnipro, completed in 1961. Compared to the Kyiv, its size was reduced by a third, while its speed increased to 20,000 operations per second. Most importantly, it was a relatively mass-produced product, with around 500 units produced.

Concurrently, Glushkov designed a much smaller computer called Promin (“Ray”), which, although far from fitting on a desk, could be placed in a room. Despite its relatively modest speed of 1,000 operations per second, its primary purpose was engineering calculations.

Essentially, Promin and its successors — MIR (which is acronym for “Machine for Engineering Calculations” in Russian) and MIR-2 — were personal computers, as it was directly used by engineers rather than specially trained programmers. The last of these modifications, created in 1969, not only had a keyboard resembling an electric typewriter but also a screen based on a cathode-ray tube.

Nationwide Automated System

However, the computers themselves were not Glushkov’s ultimate goal. As early as 1962, he pondered creating a computer network that would connect thousands of machines throughout the Soviet Union. Initially, this system was called EGSVC (which is acronym for “Unified National System of Computing Centers” in Russian), but after the project was presented to the state leadership, it was renamed OGAS (“All-State System for Collection and Processing of Information”). Initially, this system was top-secret, and then its project got lost.

When the concept was revisited in the late 1990s, very little information was available, and the topic became heavily mythologized. Some saw OGAS as an equivalent of the internet that could have been created a decade earlier than Western networks. Others argued that it was just a failed attempt by a totalitarian state to control everything, and it had nothing in common with the modern World Wide Web.

More information about OGAS can be found in Viktor Glushkov’s book “Foundations of Paperless Informatics,” published immediately after his death in 1982. According to the book, this system was indeed conceived for the Soviet planned economy, but it could also have been used to combat excessive bureaucracy in any state management system.

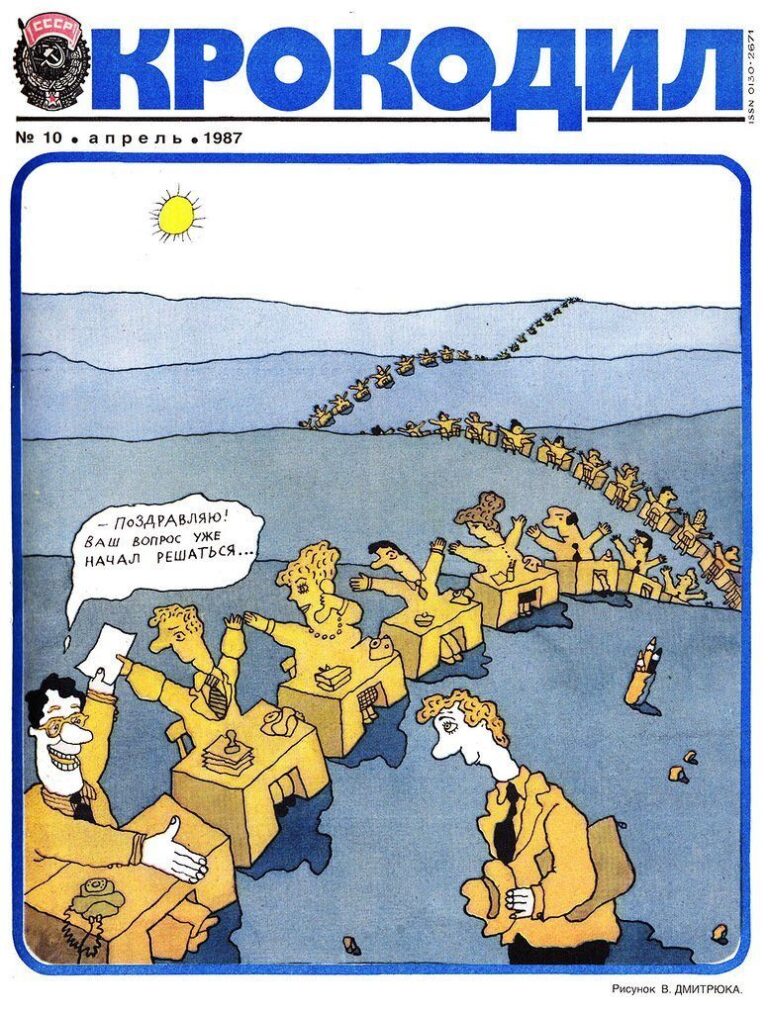

Glushkov realized the vast amount of government paperwork that institutions had to exchange to gather information and receive necessary feedback. He was well aware of the frequent and frustrating errors that could occur in such a system.

Since most of the requests were repetitive, he proposed a simple solution: let the required information be stored and updated in electronic form, accessible from any computer in the network. He essentially proposed the creation of databases and remote access to them.

Additionally, the system was meant to allow users to collaborate on tasks like planning. This somewhat resembled modern cloud services like Google Docs. A team of system administrators would manage the network, ensuring the functioning of services and distributing the computing power of unused computers among those who needed it.

This last point was crucial as the computational power of the machines at that time was limited. Thus, OGAS would have been something like a “government in a smartphone” (this is the name of the successful project by Ukrainian government) except the required computer would fill a room, not a pocket.

Therefore, according to Glushkov’s vision, the OGAS network would rely on over 200 foundational computing centers together with computing centers of individual plants and institutions, which then would provide services to users.

This all gives grounds to say that OGAS was not the internet at all. To use it, one would need to visit a computing center, navigate Soviet bureaucracy to submit a message, have it transmitted to a foundational computing center, then to the main network center, and from there to another center. This would be impractical.

However, in reality OGAS was planned to work differently. Firstly, direct communication channels were to exist between the foundational computing centers. Glushkov was among the first to emphasize the importance of horizontal connections in state management. He proposed a way to digitally include these connections into the system.

Secondly, each computing center of individual institutions would have numerous terminals that provided access to shared memory and computing resources. In essence, this architecture was not much different from an office LAN with higher-level network connectivity. A service similar to modern email would have been available to each user, of which there were many.

Whatever the case, OGAS was never implemented in the Soviet Union. Initially, various levels of officials fiercely resisted it as it threatened their usual way of doing things marked with corruption and procrastination. Later, it turned out that there weren’t enough computers being produced in the USSR, so efforts were made to increase their production.

Finally, when the OGAS construction program was accepted in the early 1970s, it turned out that technology had advanced significantly, and it quickly became outdated.

Computer Lag of the Soviet Union

The question of the feasibility of Viktor Glushkov’s OGAS (All-State Automated System) is closely linked to the issue of the lag in the Soviet electronic industry, often framed as: “While the US had personal computers, the USSR still used punched cards and vacuum tubes.” However, the situation was a bit more complex than that.

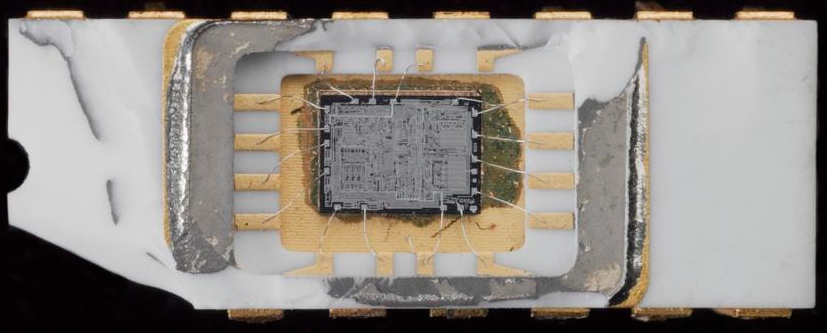

When Glushkov entered cybernetics from mathematics in the 1950s, the Soviet Union had a similar level of computing technology as the US. In both places, computers filled entire rooms and used vacuum tubes and transistors. Furthermore, the concept of integrating a large number of transistors onto a single chip, known as an integrated circuit or microchip, was already being explored. Most modern electronic devices are built upon this technology.

The microchip breakthrough occurred in the West in 1959, a year after Glushkov had already created his first computers. The Soviet analogue appeared relatively quickly in 1961. Throughout the 1960s, the transition to the new element base was ongoing on both sides of the “Iron Curtain.” Computers still looked like huge wardrobes with terminals attached to them. While the USSR was slightly behind, the gap was not significant.

The breakthrough in the West happened in 1971 when Intel managed to fit an entire processor onto a single microchip. Though the first chip wasn’t very powerful and suited more for calculators, more advanced versions were developed by 1974. This allowed the creation of personal computers capable of running programs and processing data while fitting on a desk.

These computers gradually and then rapidly conquered the world, forming the basis for electronic networks, as opposed to computing centers. In the USSR, processors analogous to those developed by Intel appeared in the late 1970s, and computers were built based on them. However, the Soviet industry couldn’t keep up with the competitors. The number of transistors on microchips was growing rapidly every year, making computers obsolete in no time. Glushkov realized all of this well, but he couldn’t change the situation.

Glushko as a Vice President of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences was perhaps one of the best-informed individuals in the USSR regarding matters that most Ukrainians would only experience in the 1990s or even the 2000s. Cashless bank transfers and contactless card payments were familiar to him. He was also interested in computer-based text editing and electronic document preparation for printing, where a file is sent directly to a printer.

Throughout his life, Glushkov was deeply interested in artificial intelligence. In his book “Foundations of Paperless Informatics,” he described intelligent systems for recognizing printed and spoken language. He accurately identified the path to building a system capable of handling such tasks through statistical analysis. His assertion that a system called a perceptron could implement this principle was spot on. In the 1990s, decades after Glushkov’s death, multilayer perceptrons started being referred to as neural networks.

Is a “digital nation” possible in Ukraine?

Throughout his life, Glushkov struggled with Soviet bureaucracy. He fought against it despite being not just a member of the Communist Party, but also a deputy of the Soviet Supreme Council. He dedicated 25 years to cybernetics — the science of data transmission, storage, and transformation in control systems, regardless of whether they are machines, living beings, or society.

In the USSR, until 1955, a year before Glushkov moved to Kyiv, cybernetics was considered a “pseudoscience”. Even after its “rehabilitation,” the majority of the population and the Soviet bureaucracy continued to view Glushkov’s ideas with hostility.

It’s hard to believe, but proponents of the idea of state control over the economy and society, as well as the scientific approach, strongly resisted the application of the same approach in state management! Everyone understood that information transmission in the immense governmental system was highly inefficient. However, they were not willing to trust machines with the tasks that an army of bureaucrats was handling.

The issue he faced is still relevant today. Wherever we encounter bureaucratic processes that require paper forms instead of digital services, we face the same problem Glushkov fought against.

He understood that in even the most advanced computerized management systems, a human element would always remain. This element needed to be prepared to interpret and make decisions based on the information provided by the machines. Hence, in the later years of his life, Glushkov dedicated his efforts to popularizing computer technology in a society still reliant on paper-based systems, aiming to teach people that computers were their allies.

Remarkably, something remotely resembling Glushkov’s “paperless informatics” was only achieved in Ukraine three decades after the arrival of personal computers and their networks. It was implemented as “government in a smartphone” project which is being implemented in Ukraine right now. We can only hope that the ongoing battle against bureaucracy will end in victory.