The dwarf planet Ceres has a diameter of about 1000 kilometers and is the largest object in the asteroid belt. At the same time, it is quite different from its neighbors by its complex geology and the presence of traces of cryovolcanism. All of these may indicate that it has formed in the wrong place.

Dwarf planet in the asteroid belt

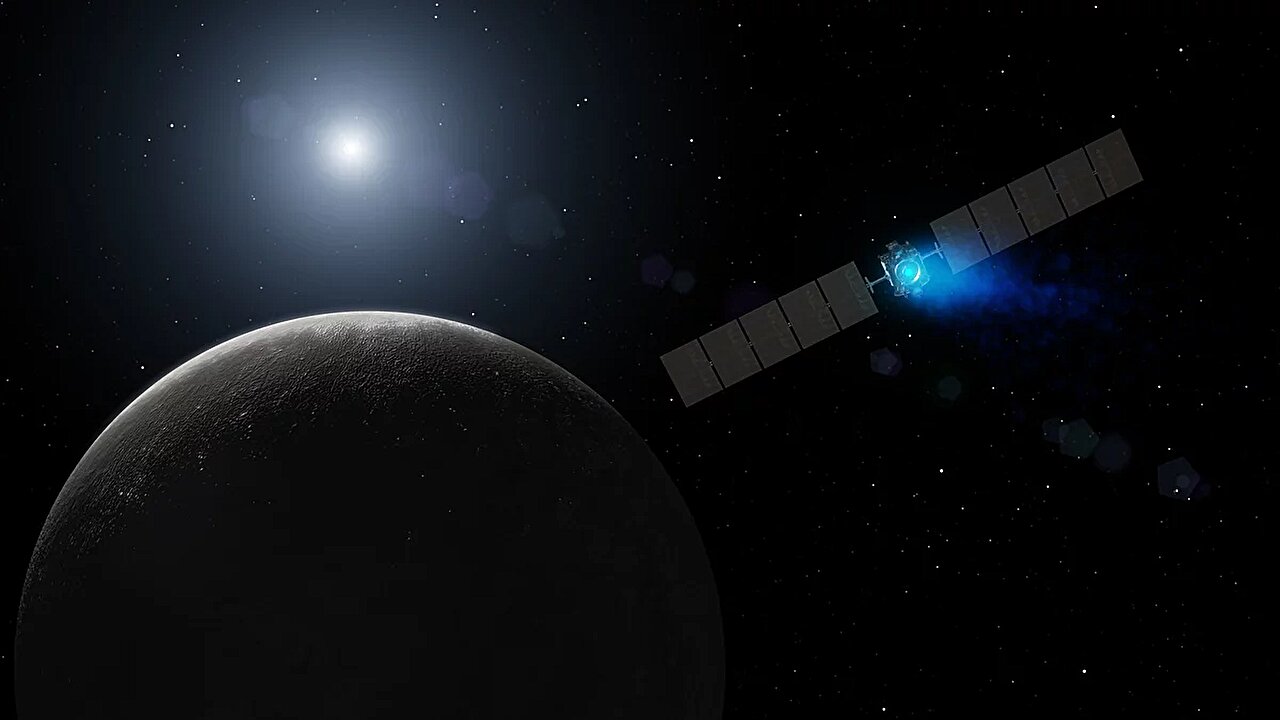

The dwarf planet Ceres has a diameter of almost 1000 kilometers and is located in the asteroid belt. For a long time, it was not entirely clear whether the dwarf planet had formed in the asteroid belt or migrated there from somewhere outside Jupiter’s orbit. A research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen has found ammonium-rich deposits at the Consus Crater in data from NASA’s Dawn space probe that reveal much about the origin of Ceres.

Ceres is an unusual “resident” of the asteroid belt. With a diameter of about 960 kilometers, it is not only the largest body between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, but unlike its rather simple “cohabitants” is characterized by an extremely complex and diverse geology. Years ago, NASA’s Dawn space probe discovered vast deposits of ammonium on the surface of Ceres.

Some researchers suggest that solidified ammonium played a role in the formation of the dwarf planet. However, ammonium is only stable in the outer space of the Solar System, indicating that it originated away from the asteroid belt. However, new findings from the Consus Crater suggest against this.

Cryovolcanism

Until recently, Ceres was the scene of unique cryovolcanism — and probably remains so to this day. The main data were obtained by NASA’s Dawn space probe while studying Ceres closely from 2015 to 2018. These data point to an eventful past in which Ceres has been changing and evolving for many billions of years.

Light, whitish salt deposits can be found in several impact craters. Sediments in Consus Crater may indicate ammonium-rich material that reached the surface from deep within the dwarf planet due to Ceres’ volcanism. More specifically, researchers believe the sediments are remnants of brine that seeped to the surface from the liquid layer between the mantle and crust over many billions of years.

Images and measurement data from the Consus Crater, which the team has now analyzed in more detail than ever before, now show such material having a yellowish color. Consequently, the presence of ammonium doesn’t necessarily indicate an origin from the outer Solar System — Ceres could have formed where it orbits today.

Crater within a crater

The crater Consus is located on the Southern Hemisphere of Ceres. With a diameter of about 64 kilometers, it doesn’t belong to especially large impact craters of the dwarf planet. Images taken by the Dawn scientific camera system, designed and built under the direction of MPS, show a circular crater wall that rises about 4.5 kilometers above the crater floor and is partially eroded inside.

It surrounds a smaller crater measuring approximately 15 by 11 kilometers that dominates the eastern half of the floor of the crater Consus. Yellowish, bright material appears as isolated dots exclusively at the edge of the smaller crater and in the area slightly east of it.

The yellowish-bright material in Consus Crater is rich in ammonium, as a new analysis of data from the camera system and VIR spectrometer shows. This compound, which differs from ammonia in having an additional hydrogen ion, is almost everywhere on the surface of Ceres in the form of ammonium-rich minerals.

Previously, scientists believed that these minerals could only have formed due to contact with ammonium ice in the cold conditions at the outer edge of the Solar System, where frozen ammonium is stable for long periods of time. Closer to the Sun, it quickly disappears. So, Ceres probably formed at the edge of the Solar System and only later “moved” to the asteroid belt, the scientists concluded.

The current study shows for the first time a link between ammonium and salty brine from Ceres’ interior. The team claims that the origin of the dwarf planet doesn’t necessarily have to be in the outer Solar System in this way. Ceres may also originate from the asteroid belt.

Ammonium from the depths

The researchers hypothesized that ammonium components were already contained in Ceres’ primary building blocks. As ammonium doesn’t combine with the typical minerals of Ceres’ mantle, it gradually accumulated in a thick layer of brine that stretched between the dwarf planet’s mantle and crust.

There is much indication that ammonium concentrations are greater in the deeper layers of the crust than near the surface. There are few places on Ceres’ surface where prominent areas of yellowish-bright material can be found outside of Consus Crater, and they are also located inside deep craters.

As this study details, the impact that created the small eastern crater only 280 million years ago probably exposed material from the depths, particularly the ammonium-rich layers in Consus Crater. The yellowish-bright spots to the east of the smaller crater are material ejected by the impact.

“At 450 million years, Consus Crater is not particularly old by geological standards, but it is one of the oldest surviving structures on Ceres. Due to its deep excavation, it gives us access to processes that took place in the interior of Ceres over many billions of years-and is thus a kind of window into the dwarf planet’s past,” said MPS researcher Dr. Ranjan Sarkar, a co-author of the study.

According to phys.org