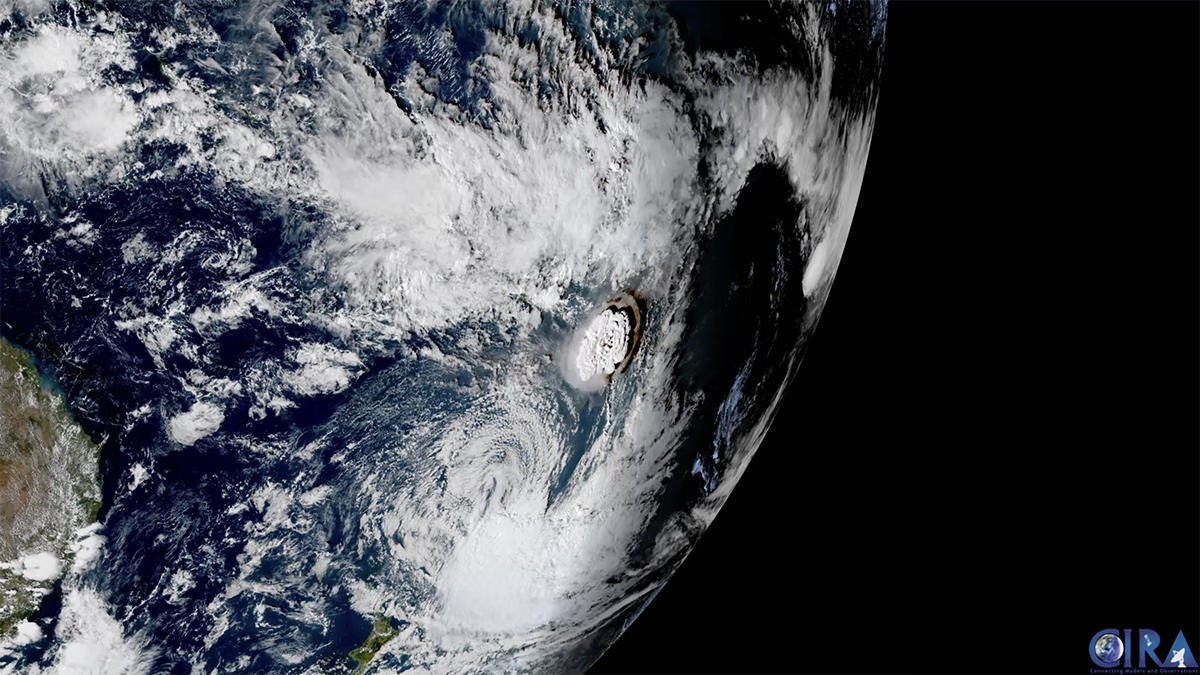

On January 15, 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai underwater volcano erupted, causing a tsunami that devastated infrastructure and caused casualties in the Kingdom of Tonga. One of the main consequences of this largest underwater explosion recorded by modern instruments was the release of huge amounts of aerosols and water vapor into the atmosphere.

Schoeberl and colleagues investigated the impact of the eruption on climate in the Southern Hemisphere over the next two years. It turned out that during the first year, the cooling effect from volcanic aerosols reflecting sunlight was stronger than the warming from water vapor, which trapped heat. But most of these impacts disappeared by the end of 2023.

Scientists analyzed satellite data on changes in aerosols, gases and temperature in the stratosphere. The eruption released about 150 megatons of water vapor into the atmosphere, which increased its level in the stratosphere by 10%. This led to a 4°C decrease in tropical stratospheric temperatures in March-April 2022, and also contributed to secondary circulation, resulting in lower ozone levels throughout the year.

The eruption also released 0.5 to 1.5 megatons of sulfur dioxide, producing sulfate aerosols, into the stratosphere. These aerosols reflect sunlight and can cause a decrease in surface radiative forcing, leading to global cooling. However, aerosol volumes from the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai volcano were relatively small, and their impact was predominantly confined to the Southern Hemisphere in 2022 and 2023.

Although the eruption affected the Earth’s radiation balance, the change was minimal: a decrease in radiation flux of less than 240 watts per square meter over two years. This short-term cooling in the Southern Hemisphere would be difficult to track based on meteorological data alone.

According to livescience.com