“Comets are like cats: they have tails, and they do precisely what they want.”

David H. Levy, ‘Comets: Creators and Destroyers’

Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) has captured the interest of both scientists and amateur astronomers since early last year. It’s sparked a lot of debate and is now being watched closely around the globe. After a few weeks of silence, while the comet was too close to the Sun, the first images from the Southern Hemisphere are finally starting to come in. As the moment of truth draws closer, we’ll soon find out if this comet lives up to the hype.

A tiny, distant speck: how the comet first appeared to the world

Every year, astronomers discover dozens of new comets, but only a few really stand out. The last comet to captivate both experts and casual observers was C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE), which lit up the evening sky in the summer of 2020. Now, we’re eagerly awaiting a new tailed visitor that promises to be just as impressive.

Comet C/2023 A3 was officially discovered on January 9, 2023, when it was first photographed at the Zijinshan Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. At that time, the comet was 7.7 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, positioned between the orbits of Saturn and Jupiter. With a magnitude of just 18.7m, it appeared as a faint, barely noticeable star that moved in the Serpens constellation.

A month and a half later, on February 22, the comet was discovered independently by the South African Astronomical Observatory using the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS). By then, its brightness had slightly increased to 18m.

Typically, as soon as a comet is discovered, its data is added to a special list at the Minor Planet Center, or MPC, to await confirmation. Other observatories or independent observers usually confirm it within a few days or even hours. So, on January 9, 2023, the Chinese scientists promptly sent the new comet’s data to the MPC. Strangely, the discovery went unconfirmed for three weeks, and the comet was eventually removed from the list of objects needing further observation, as it was considered lost. When the ATLAS team reported the comet to the MPC again, this time under the code name A10SVYR, it was confirmed within a few days. On February 28, the comet was officially named C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS), in honor of both observatories that discovered it.

Early sightings

Almost immediately after its discovery, comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) was expected to light up the sky in the autumn of 2024. A comet’s brightness depends on several factors, including the size of its nucleus, its activity, its closest approach to the Sun, and its position relative to Earth at that time.

By a stroke of luck, the comet was captured with the 1.2-meter telescope at Palomar Observatory on December 22, 2022, even before its official discovery. This early sighting helped scientists refine its orbit. They discovered that the comet is approaching us from a distant region of the Solar System — the Oort Cloud — following a parabolic trajectory.

Since early 2024, the comet has become increasingly visible through medium telescopes, prompting regular observations by amateur astronomers, including the popular Ukrainian observer Taras Prystavski. As the comet approached the Sun, its brightness grew, and its dust tail became longer and denser, much to the delight of those watching.

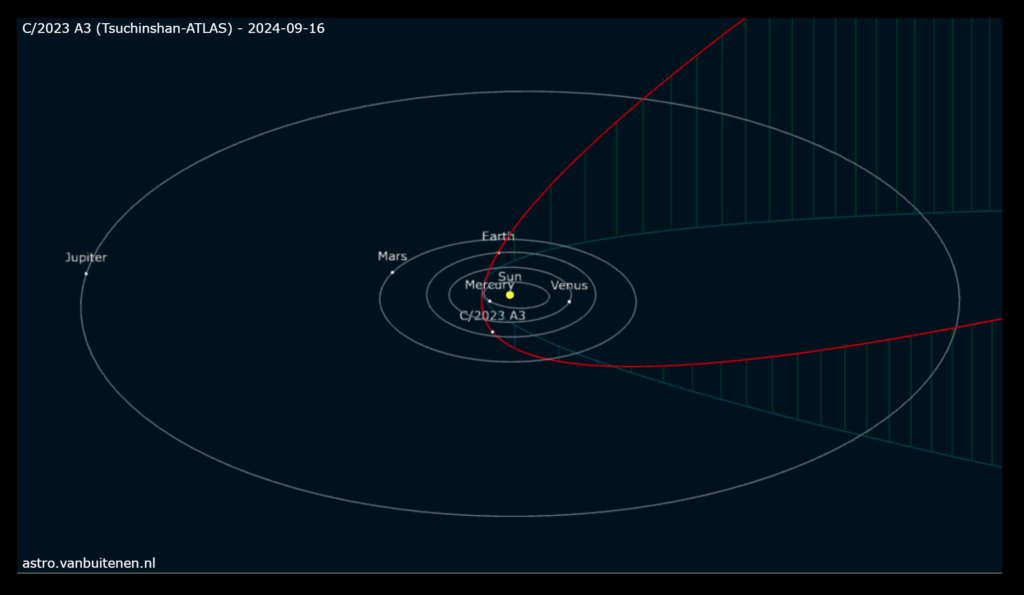

On September 27, 2024, the comet will reach perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun, coming within 0.39 AU — about the same distance as the Sun is from Mercury. Then, on October 13, it will be closest to Earth, at just 0.47 AU. After that, the comet will gradually move away from the center of the Solar System and will likely eventually leave it.

Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is quite the unpredictable guest. Its non-elliptical orbit suggests it’s a dynamically new comet, which means it’s making its first pass near the Sun. The comet’s nucleus is a ‘dirty snowball’ — a loose mix of frozen gases and cosmic dust. As it gets closer to the Sun, these gases start to melt, creating the comet’s atmosphere, also known as coma. Along with the gases, dust gets swept up, forming a long tail behind the comet. However, the Sun’s heat also increases gas pressure inside the nucleus, which could break apart before it gets close to the Sun. This unpredictability adds to the excitement, keeping scientists on the edge of their seats and eagerly awaiting the outcome.

Will it break apart or survive? The comet fragmentation debate

In early July, the scientific community was stirred by a paper from the seasoned Czech-American comet researcher Zdeněk Sekanina. At the age of 88, he remains active in his research and continues to publish his findings. In his article titled “Inevitable Endgame of Tsuchinshan-ATLAS (C/2023 A3),” Sekanina suggested that the comet might fall apart long before reaching perihelion. He even noted signs of this happening already, as the comet’s brightness had stopped increasing and even begun to slightly decline.

This alarming news quickly spread through the scientific community, sparking heated debates. Both professionals and amateurs ramped up their observations to see if the comet’s nucleus had indeed broken apart.

Fortunately, these concerns were unwarranted. The comet’s nucleus still appears “healthy”, and its integrity remains intact. Astronomers who study comets concluded that Sekanina might have overlooked an important factor affecting the comet’s brightness — the phase angle. This is the angle between the directions to the Sun and to the observer, with the object of observation at the apex.

In April, the comet’s opposition caused light to scatter off its tail dust particles, reflecting directly to observers on Earth — a phenomenon known as the opposition surge or backscattering. At the same time, the solar wind pushed the comet’s tail towards its head, increasing its brightness even further.

During summer, the relative positions of the Sun, Earth, and the comet changed significantly. As the comet drew closer to the Sun, it started to develop a long gas tail in addition to its dense dust tail. However, by mid-August, the comet vanished from our view, obscured by the bright sunlight.

Forecasts and observations

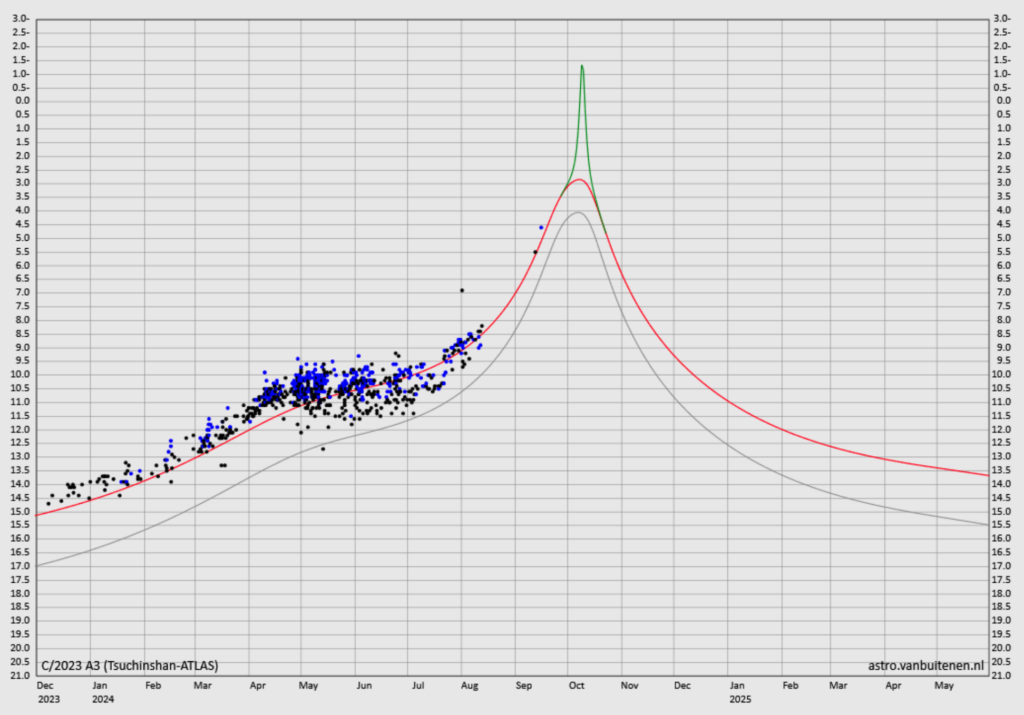

Shortly after comet C/2023 A3 was confirmed, Gideon van Buitenen published a prediction of its changes in brightness. The gray curve in the graph below shows the initial forecast from the Minor Planet Center Electronic Circular, while the red curve is based on actual observations. Even with the most pessimistic estimates, the comet was expected to reach a brightness of about 3m during its closest approach to Earth on October 12–14, making it visible in the still-bright western sky. What’s particularly intriguing in the graph is the green peak, which predicts a brightness of up to -1.5m, making it brighter than Sirius. This peak accounts for the forward scattering, which occurs when the phase angle is close to 180°, with the comet positioned almost directly between us and the Sun.

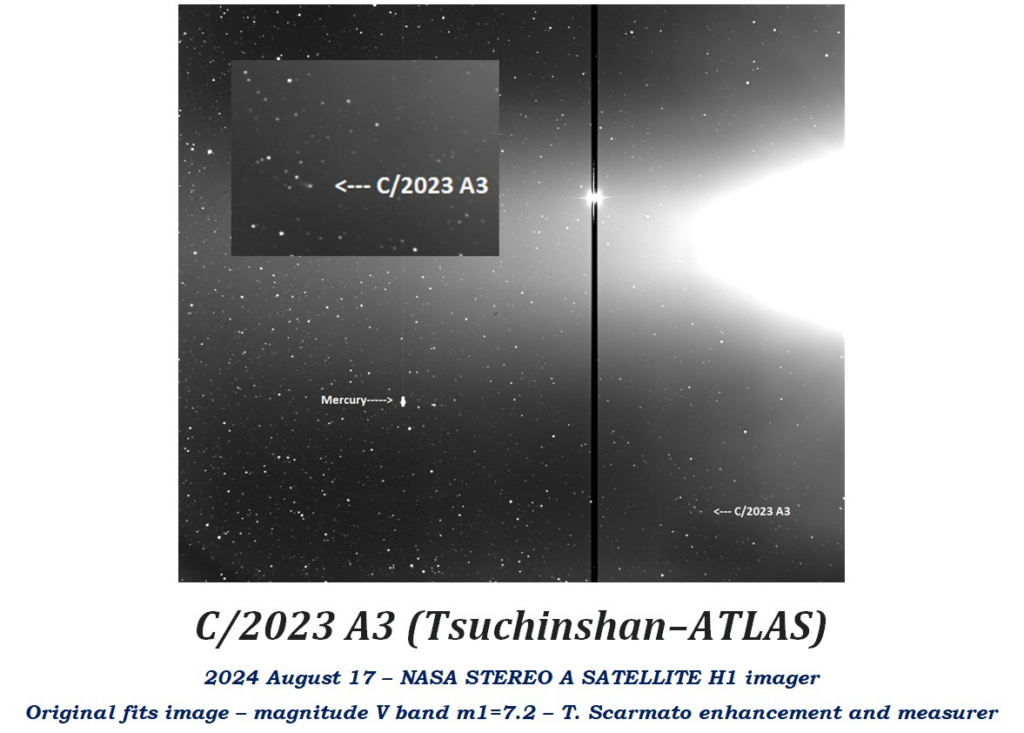

In late August and early September, traditional visual and photographic observations were joined by more unconventional ones. Although the comet was too close to the Sun for Earth-based observers, it was visible to the STEREO-A and SOHO space solar telescopes.

On September 10, the forecast for the comet’s peak brightness was updated following Joseph Marcus’ study. He estimates that, on October 9, the comet could reach an incredible magnitude of -4.8m due to forward scattering, making it appear brighter than Venus. The only drawback is that the comet will be close to the Sun at the time, making it impossible to observe from Earth.

On the morning of September 12, Terry Lovejoy, a renowned amateur astronomer who has discovered six comets, and comet hunter Michael Mattiazzo managed to photograph C/2023 A3 from the Southern Hemisphere, capturing it in the early morning light. At that time, the comet’s brightness was about 5.5m. However, it was increasing rapidly, and by September 15, Lovejoy estimated its brightness at 4.8m.

The most recent observation, captured by Michael Mattiazzo with binoculars on September 16 before dawn, shows the comet at a magnitude of 4.6m. This value is slightly higher than expected, which is exciting for comet watchers who are eagerly anticipating the perihelion.

It’s worth noting that ‘Great Comets’ often experience a very short-lived peak in brightness. After a close pass by the Sun, they tend to fade quickly, although their tails can remain impressively long for some time.

Look up!

The comet is currently visible only from the Southern Hemisphere. It can be seen low on the eastern horizon just before sunrise. However, both amateur and professional observers have only about three weeks to catch a glimpse before it moves too close to the Sun again.

For those in the Northern Hemisphere, including the US, the comet is expected to make a bright and spectacular appearance as it emerges from the Sun’s glare on October 12-13, showcasing a stunning, bushy tail. The best days for observing it will be October 12-15. If the comet lives up to its potential brightness, it could be visible as early as October 10-11, though it will be low on the western horizon right after sunset.

Despite thousands of years of study, comets remain quite unpredictable, especially those making their first approach to the Sun. In less than two weeks, as C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) nears perihelion, we’ll find out what the comet has in store. Will it shine brighter than the brightest stars? Will it rival Jupiter or even outshine Venus? And will it be visible in daylight after perihelion? It’s hard to say for sure. As the famous comet discoverer David H. Levy once said, “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and they do precisely what they want.”