Astronomers have solved the mystery of the brown dwarf Gliese 229B. Given its mass, it should be much brighter than it is. It turns out that they are actually twins, a pair of objects occupying an intermediate position between planets and stars.

Mysterious brown dwarf

Hundreds of papers have been written about the first known brown dwarf, Gliese 229B, since it was discovered by researchers at the California Institute’s Palomar Observatory in 1995. But a burning mystery regarding this ball remains: the ball is too dim for its mass.

Brown dwarfs are lighter than stars and heavier than gas giants such as Jupiter. And although astronomers have measured that Gliese 229B has about 70 times the mass of this gas giant, an object of that weight should shine brighter than telescopes have observed.

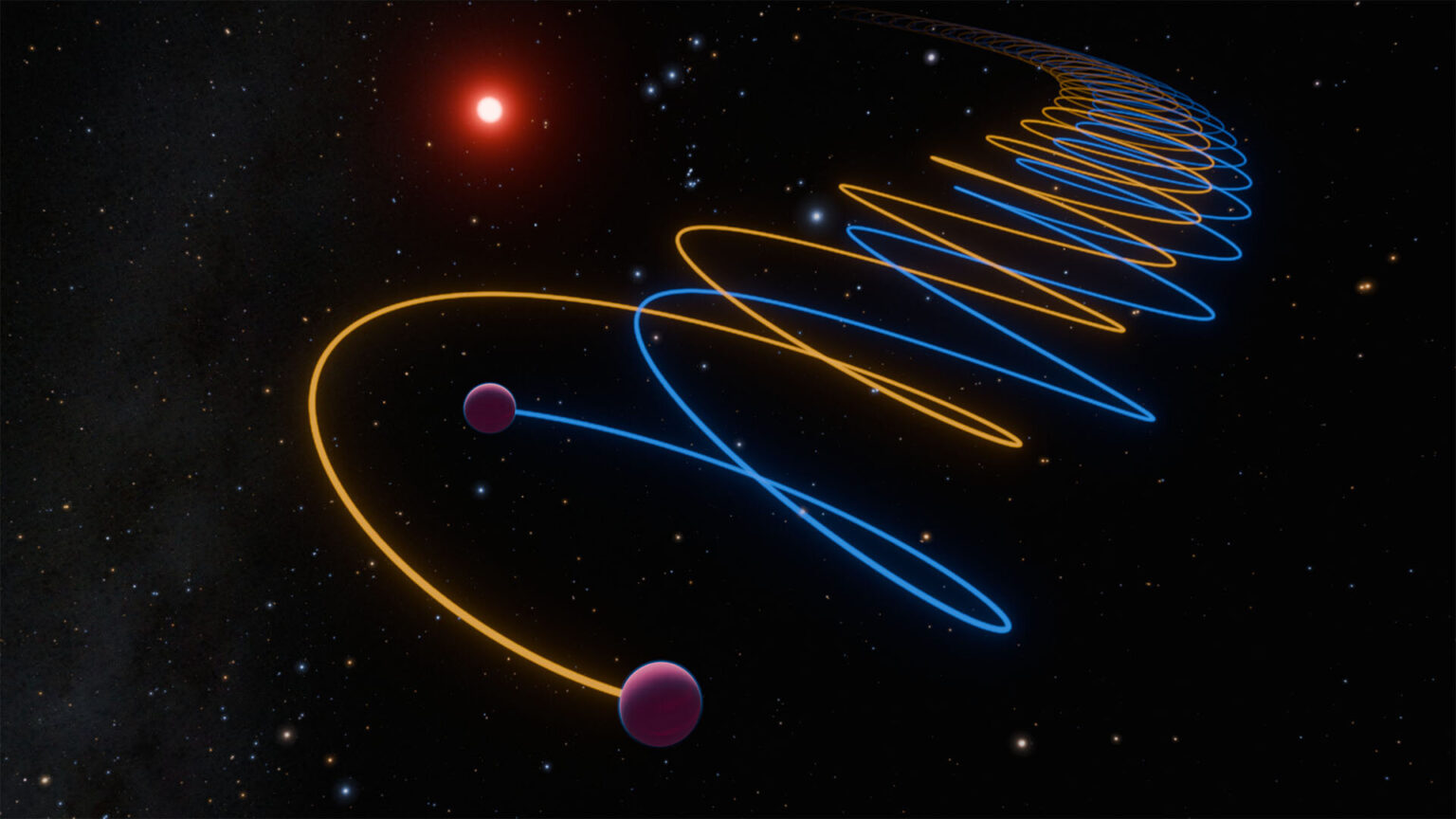

Now an international team of astronomers led by the California Institute of Technology has finally solved the mystery: the brown dwarf is actually a pair of tightly bound brown dwarfs, with masses about 38 and 34 times that of Jupiter, orbiting around each other every 12 days. The observed brightness levels of the pair are the same as expected for two small, dim brown dwarfs in this mass range.

“Gliese 229B was considered the poster-child brown dwarf,” says Jerry W. Xuan, a graduate student working with Dimitri Mawet, the David Morrisrow Professor of Astronomy. “And now we know we were wrong all along about the nature of the object. It’s not one but two. We just weren’t able to probe separations this close until now.”

Unraveling the nature of Gliese 229B

A separate independent study in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, led by Sam Whitebook, a graduate student at the California Institute of Technology, and Tim Brandt, an associate astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, also found that Gliese 229B is a pair of brown dwarfs.

This discovery raises new questions about how close brown dwarf duos like this one form, and suggests that similar binary brown dwarfs — or even exoplanets — may await discovery.

The fact that Gliese 229B is binary not only resolves the recent tension observed between its mass and luminosity, but also greatly advances our understanding of brown dwarfs at the boundary between stars and giant planets.

Gliese 229B was discovered in 1995 by a Caltech team that included Rebecca Oppenheimer, then a Caltech graduate student, Shri Kulkarni, the George Ellery Hale Professor of Astronomy and Planetary Science, Keith Matthews, a Caltech instrument specialist, and other colleagues.

Astronomers used the Palomar Observatory to discover that Gliese 229B has methane in its atmosphere, a phenomenon common to gas giants like Jupiter but not to stars. The discovery was the first confirmed detection of a class of cold star-shaped objects called brown dwarfs — the missing link between planets and stars, which theoretically existed about 30 years ago.

“Separation” of the Gliese 229B system

Nearly 30 years after its discovery and hundreds of observations, Gliese 229B was still puzzling astronomers with its unexpected dimness. Scientists suspected that Gliese 229B might be twins, but “to evade notice by astronomers for 30 years, the two brown dwarfs would have to be very close to each other,” says Xuan.

To separate Gliese 229B into two objects, the team used two different instruments, based at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. They used the GRAVITY instrument, an interferometer that combines light from four different telescopes, to spatially separate the body into two objects, and the CRIRES+ instrument (a high-resolution cryogenic infrared echelle spectrograph) to detect different spectral signatures from the two objects.

The last method entailed measuring the motion (or Doppler shift) of molecules in the brown dwarfs’ atmospheres, indicating that one body moved toward us, to Earth, and another moved away from us, and vice versa, as they orbited each other.

These observations, made over a five-month period, showed that the duo of brown dwarfs, now called Gliese 229Ba and Gliese 229Bb, orbit each other every 12 days with a distance that is only 16 times the distance between Earth and the Moon. Together they orbit an M-dwarf star (smaller and redder than our Sun) every 250 years.

Mysteries of the brown dwarf double system formation

How this swirling pair of cosmic bodies came into life is still a mystery. Some theories claim that the pair of brown dwarfs could have formed inside the swirling disks of matter surrounding the forming star. The disk disintegrates into two brown dwarf seeds, which become gravitationally bound after a close encounter. Indeed, it remains to be investigated whether these same formation mechanisms work for the formation of pairs of planets around other stars.

In the future, the team hopes to search for even closer orbits of binary brown dwarfs using instruments such as the Keck Planet Imager and Characterizer (KPIC), developed by a team led by Mawet at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawai’i, and the future High Resolution Infrared Spectrograph for Exoplanet Characterization (HISPEC), which is under construction at the California Institute of Technology, and other labs by a team led by Mawet.

According to phys.org