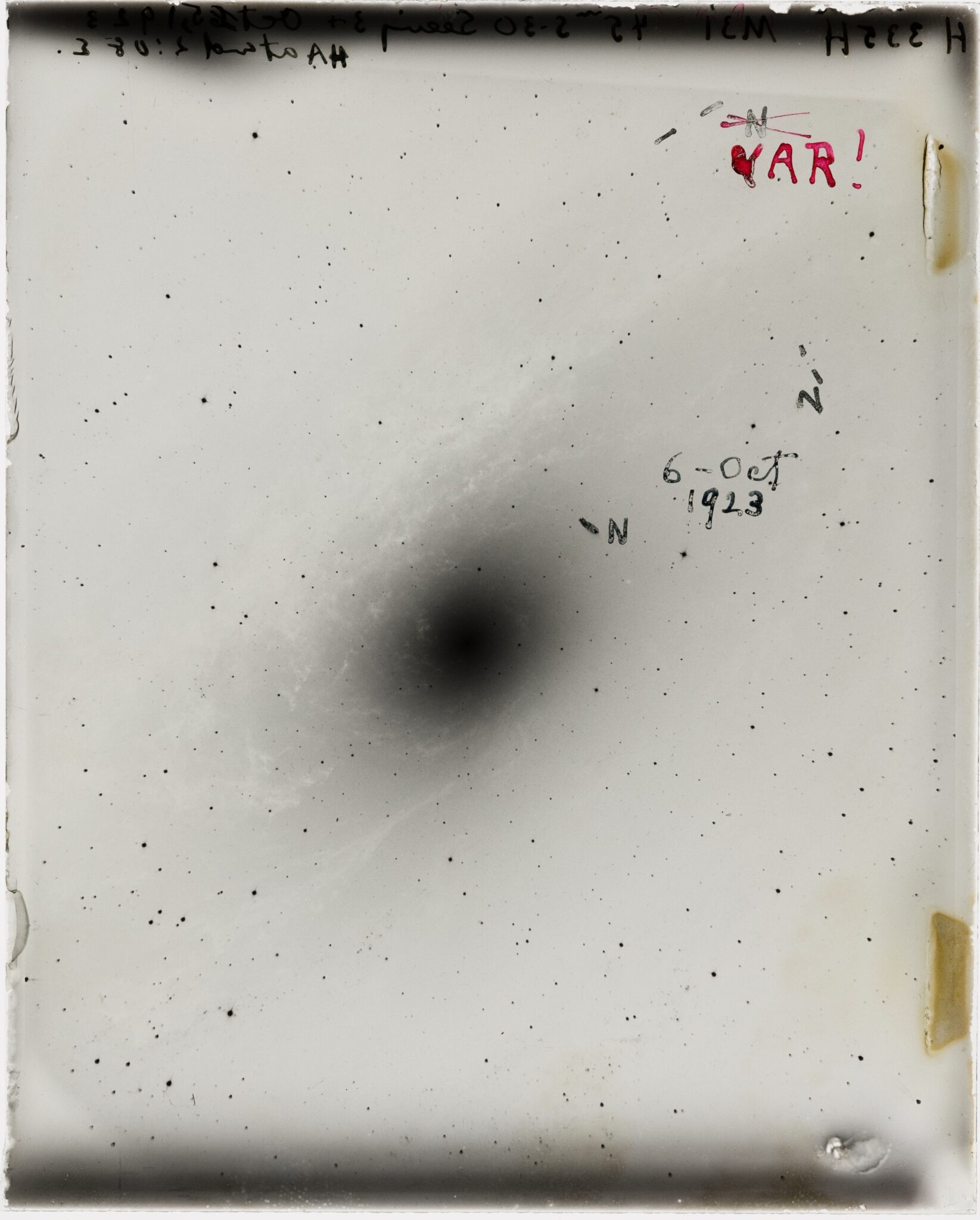

On the night of October 5-6, 1923, astronomer Edwin Hubble took a picture of the Andromeda Nebula, which was assigned the identification number H335H. This shot became one of the most important pieces of astrophotography in the history of science. Thanks to it, Hubble was able to prove that our Universe extends beyond the Milky Way.

A great controversy

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was generally accepted that our Universe is actually limited to the boundaries of our galaxy, and all the so-called spiral nebulae are part of it. Based on this assumption, astronomer Harlow Shapley estimated the diameter of the entire Universe to be about 300 thousand light years.

However, over time, another, more radical hypothesis of the so-called “island Universe” appeared in astronomical circles. According to it, the spiral nebulae were actually the same clusters of stars as our Milky Way, but were located at a great distance from it. The most famous proponent of this version was the astronomer Heber Curtis. Interestingly, although Curtis was ultimately right about the big picture, he also mistakenly believed that the size of the Milky Way was only 30 thousand light years, with the Sun at its center.

In the early 1920s, Shapley and Curtis held a series of debates on this issue that went down in the history of science as the Great Controversy over the Structure of the Universe. They did not find a clear winner. To answer the question of whether spiral nebulae are part of the Milky Way or are separate galaxies, astronomers needed to determine the distance to them. But due to a lack of observational data and the use of some erroneous assumptions, Heber and Curtis obtained very different data, none of which could be recognized as decisive.

Edwin Hubble’s historic discovery

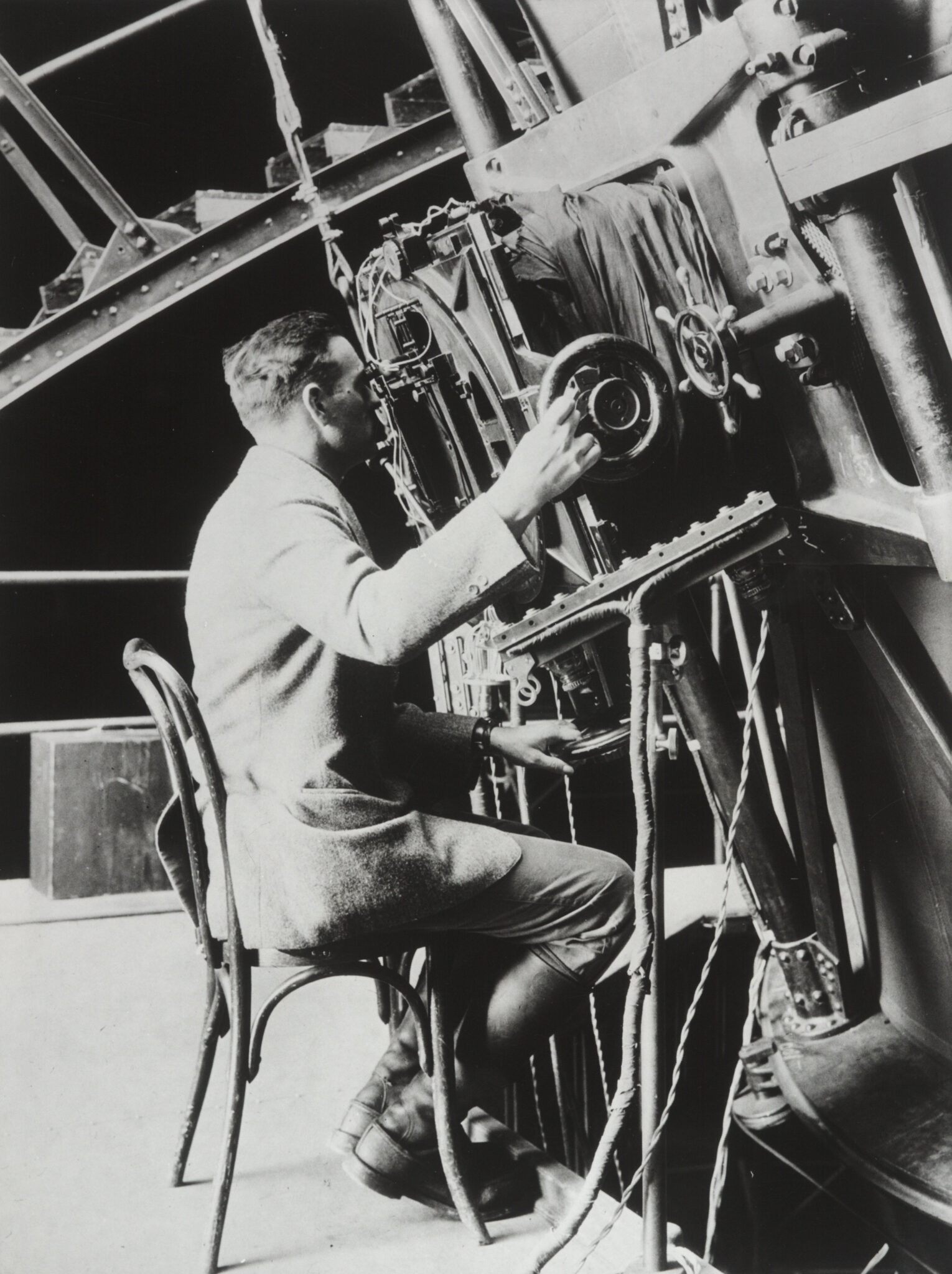

The debate about whether the Universe extends beyond the Milky Way was put to rest by Edwin Hubble. Since 1919, he worked at Mount Wilson Observatory, which at that time housed the largest optical instrument in the world, the 2.5-meter Hooker Telescope. Hubble studied spiral nebulae and, in particular, the Andromeda Nebula. The astronomer was looking for novae, hoping to use them to determine the distance. They erupt in binary systems where there is a white dwarf that absorbs the matter of its companion, which from time to time leads to the release of large amounts of energy.

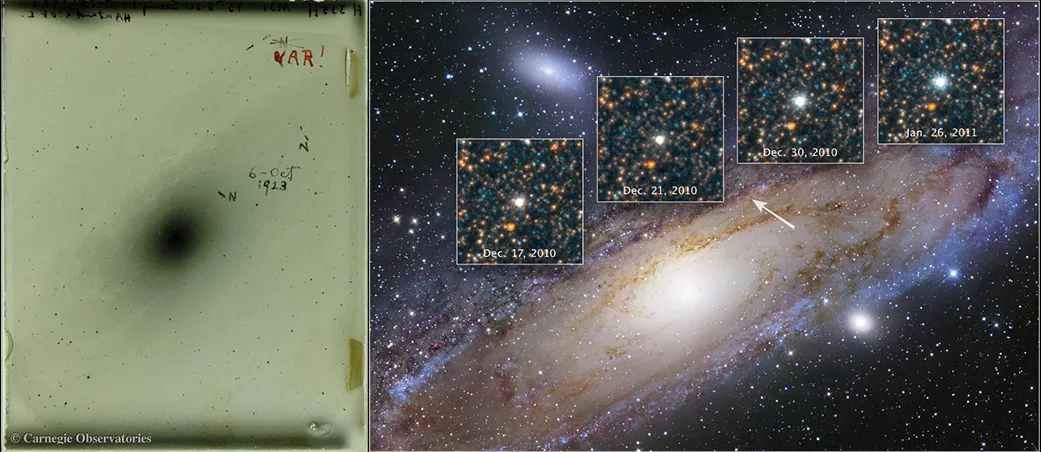

On the night of October 5-6, Hubble took another picture of the Andromeda Nebula. After comparing the resulting photographic plate with the previous image, he discovered three potential novae. However, Hubble soon noticed that one of them appeared in the same place where he had previously observed a flare. By 1923, astronomers already knew that white dwarfs take centuries or even millennia to accumulate enough material to explode again. Therefore, Hubble realized that he had found not a nova, but a cepheid. The astronomer gave it the designation V1.

Contemporaries often described Hubble as a reserved and taciturn man. But the same historic H335H photographic plate shows how much this discovery excited the astronomer. He used an exclamation point, a rare occurrence for him, to celebrate the cepheid he had found, forever memorializing this most important moment in the history of astronomy.

The fact is that cepheids are pulsating variable stars characterized by a clear dependence between their luminosity in the visible spectrum and the pulsation period. This circumstance allows them to be used as fairly reliable standard candles for determining the distance to distant objects.

And that’s exactly what Hubble did. He used V1 to determine the distance to Andromeda. His estimate was 1 million light-years (modern measurements give 2.5 million light-years), which far exceeded the size of the Universe according to Shapley’s estimate. Subsequently, Hubble managed to find cepheids in other spiral nebulae, proving that they are also located at a great distance from the Milky Way.

On February 9, 1924, Hubble sent a letter to Shapley, telling him about his discovery. Before that, Shapley had often criticized Hubble for his methods, considering them unscientific. But after checking his opponent’s calculations, Shapley told his colleague: “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.” Subsequently, Shapley supported Hubble to write a report on his discovery for a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. It was read out on January 1, 1925, forever changing the history of science and astronomers’ understanding of the structure of the universe.