Scientists propose to use methyl halides as markers for the existence of life on the planet. These gases are much easier to detect in the composition of the atmospheres of distant bodies than those substances which are usually proposed to be sought for this purpose.

Search for life by methyl halides

Scientists have identified a promising new way to detect life on distant planets, based on non-Earth-like worlds and gases that are rarely considered in the search for aliens.

In a new paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers from the University of California, Riverside, describe these gases, which can be detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets — planets outside our solar system — using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

These gases, called methyl halides, consist of a methyl group containing a carbon atom and three hydrogen atoms attached to a halogen atom, such as chlorine or bromine. On Earth, they are produced mainly by bacteria, seaweeds, fungi and some plants.

One of the key aspects of the search for methyl halides is that Earth-like exoplanets are too small and dim to be seen with JWST, the largest telescope in space.

Oceanic worlds as a place to search for life

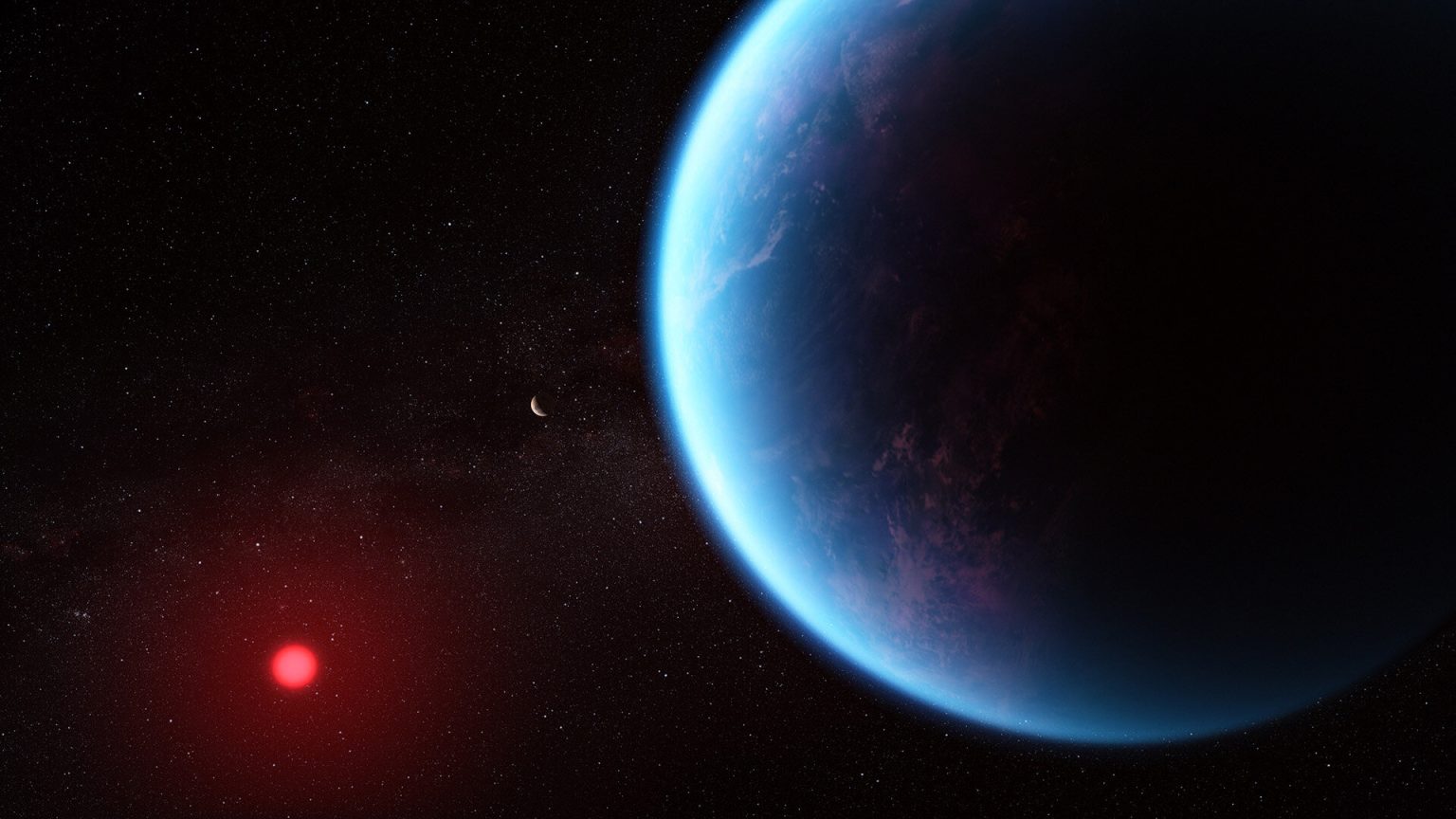

Instead, JWST should look for large exoplanets orbiting small red stars with deep global oceans and thick hydrogen atmospheres, called oceanic planets. Humans could not breathe or survive on such planets, but some microbes could thrive in such an environment.

The researchers believe that searching for methyl halides in ocean worlds is the best strategy at this point in time.

“Oxygen is still difficult or impossible to detect on an Earth-like planet. However, methyl halides in oceanic worlds offer a unique opportunity for detection with existing technologies,” said Michaela Leung, a UCLA planetary scientist and first author of the paper.

Also, finding these gases may be easier than looking for other types of biosignature gases that indicate life.

“One of the biggest advantages of finding methyl halides is that with the James Webb, they can be found in just 13 hours. That’s about the same amount of time or much less time than it takes for a telescope to find gases like oxygen or methane,” Leung said. “Less time with the telescope means less cost.”

Although life forms produce methyl halides on Earth, this gas is found in our atmosphere in low concentrations. Because the Ocean planets have a different atmospheric composition and orbit a different type of star, gases can accumulate in their atmospheres and are visible light-years away.

“These microbes, if we discovered them, would be anaerobic. They would be adapted to a completely different type of environment, and we can’t imagine what that looks like, except that these gases are a possible result of their metabolism,” said Schwieterman, a co-author of the paper.

This study builds on previous studies of various biosignature gases, including dimethyl sulfide, another potential sign of life. However, methyl halides look particularly promising because of their strong absorption in the infrared light, as well as their potential for significant accumulation in a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere.

Instruments to search for alien life

While James Webb is the best instrument for such a search, future telescopes, such as the proposed European LIFE mission, may make detecting these gases even easier. If LIFE is launched in the 2040s, as planned, it will be able to confirm the presence of these biosignatures in less than 24 hours.

“If we start finding methyl halides on many planets, it could indicate that microbial life is widespread in the Universe,” Leung said. “It would change our understanding of the spread of life and the processes leading to the origin of life.”

The researchers plan to expand the work to other types of planets and other gases in the future. For example, they have already measured gases coming from the Salton Sea, which seems to produce halogenated gases such as chloroform.

Even when researchers push the limits of detection, they recognize that direct sampling of exoplanet atmospheres remains beyond current capabilities. Nevertheless, advances in telescope technology and exoplanet exploration may one day bring us closer to answering one of humanity’s biggest questions, “Are we alone in the Universe?”