On October 24, 2007, China launched its first ever craft into interplanetary space. The Chang Zheng 3A rocket sent the Chang’e-1 automatic vehicle to the moon.

At first glance, the Celestial Empire only demonstrated the ability to repeat the achievements of the superpowers of almost half a century ago. After all, China did not even become the third country to successfully launch its apparatus to the Earth’s satellite. Japan and ESA were ahead, and just a year after the Chinese, India added to this list.

But China’s approach is markedly different from the actions of most other space players who have sent spacecraft to the moon as part of joint programs to study the solar system. For Celestial Empire, the natural satellite of the Earth is a priority goal. In recent years, the PRC has sent five research vehicles with two rovers, one repeater and two microsatellites to the Moon. This is more than the total number of lunar probes launched during the same period of time by all other countries combined. And in the near future this list will only increase. So it’s time to talk about how China systematically conquers the Moon and its plans for the near future.

The birth of the Chinese lunar program

Back in the late 1990s, the Commission for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense within the State Council of the People’s Republic of China began considering the possibility of implementing a national lunar exploration program. This was facilitated by rapid economic growth and the gradual establishment of the country on the international arena. In addition, China’s first manned space launch was just around the corner. In 2004, the country officially announced the existence of the Chang’e project, named after the Chinese goddess of the moon. The program was divided into four main phases.

- At the first stage, it was planned to send orbital devices to the Moon, capable of making detailed maps of its surface, which would allow choosing optimal places for landing future missions.

- During the second phase, stationary platforms with scientific instruments and autonomous rovers were to be landed on the surface of the Earth’s satellite.

- The next phase involves gathering samples of the lunar substance and its transportation to our planet.

- And the finale step of the Chang’e program would be the construction of a robotic research station at the south pole of the Moon.

China goes to the moon

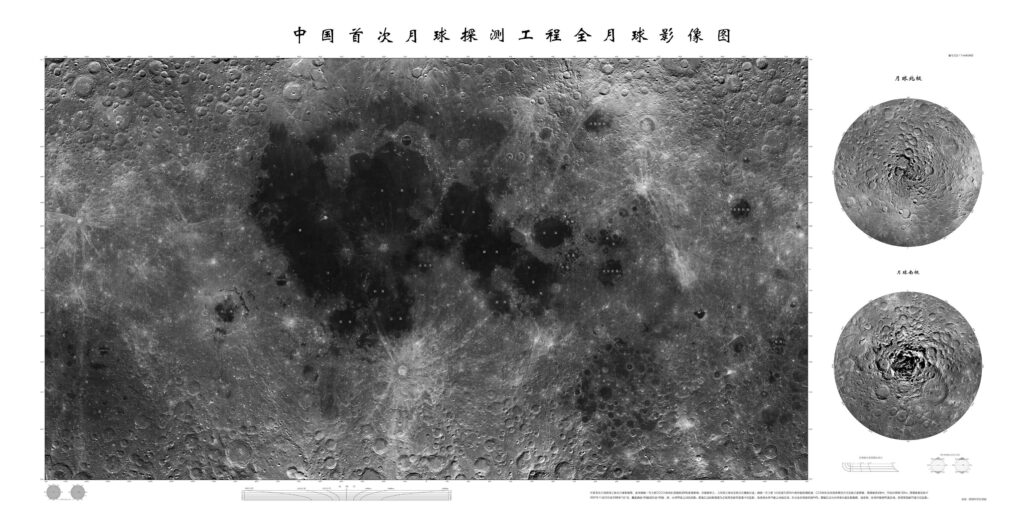

In November 2007, Chang’e-1 successfully entered a selenocentric orbit and conducted a detailed survey of the surface of our natural satellite, which made it possible to create a three-dimensional topographic map of it. The apparatus also evaluated the content of a number of chemical elements in the lunar crust. In the future, this data can be used to organize resource mining. After completing all the planned observations Chang’e-1 was de-orbited and landed on the Moon on March 1, 2009.

The global map of the Moon compiled using data from the Chang’e-1 mission.

In 2010, Chang’e-2 went to the moon. It had the same design as its predecessor, differing only in a more advanced camera and altimeter. The main task of the apparatus was to find a place for landing the next mission. It successfully coped with this task. After the main science program was completed, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) decided to use Chang’e-2 to test its capabilities for communication and control of vehicles in deep space. The probe performed a maneuver that directed it to the L2 Lagrangian point of the Sun-Earth system, and in 2011 entered a halo orbit around it. CNSA became only the third space agency in history to visit this region.

But the journey of the second Chinese lunar probe did not end there: later it was decided to turn it into an “asteroid scout”. In April 2012, the device performed a new maneuver, which transferred it to the flyby trajectory of the asteroid 4179 Toutatis. On December 13, 2012, Chang’e-2 passed at a distance of 3.2 km from it, taking a series of pictures of the surface of the small body. The resolution of the best of them was 10 m.

After the completion of the Tutatis flyby, Chinese experts continued to operate Chang’e-2 as a probe it to test the national long-distance space communication system. By 2016, the device had moved to a distance of more than 200 million km from our planet. It is currently unknown whether CNSA is still in contact with Chang’e-2.

China reaches the moon

The successes of Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 allowed the PRC to move to the next phase of its lunar program — a soft landing on the moon. It is worth noting that this is a much more difficult task than putting a satellite into a selenocentric orbit. Both for the USSR and the USA their first attempts to land automatic stations on the lunar surface were unsuccessful. India and the Israeli company SpaceIL also failed.

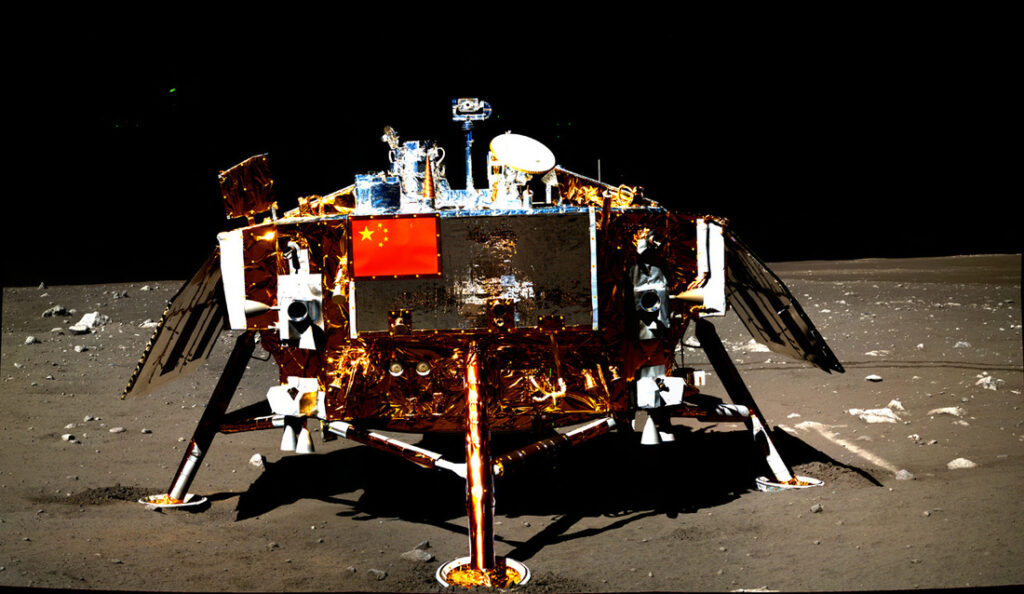

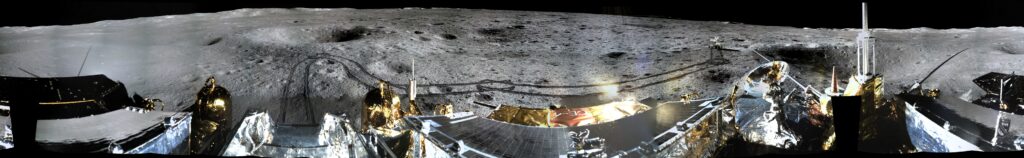

But China managed to achieve the goal with the first attempt. On December 14, 2013, the Chanye-3 spacecraft became the first Earth messenger since 1976, which made a soft landing on the surface of our planet’s satellite. It happened in the Sea of Rains, 40 km south of the Laplace F crater.

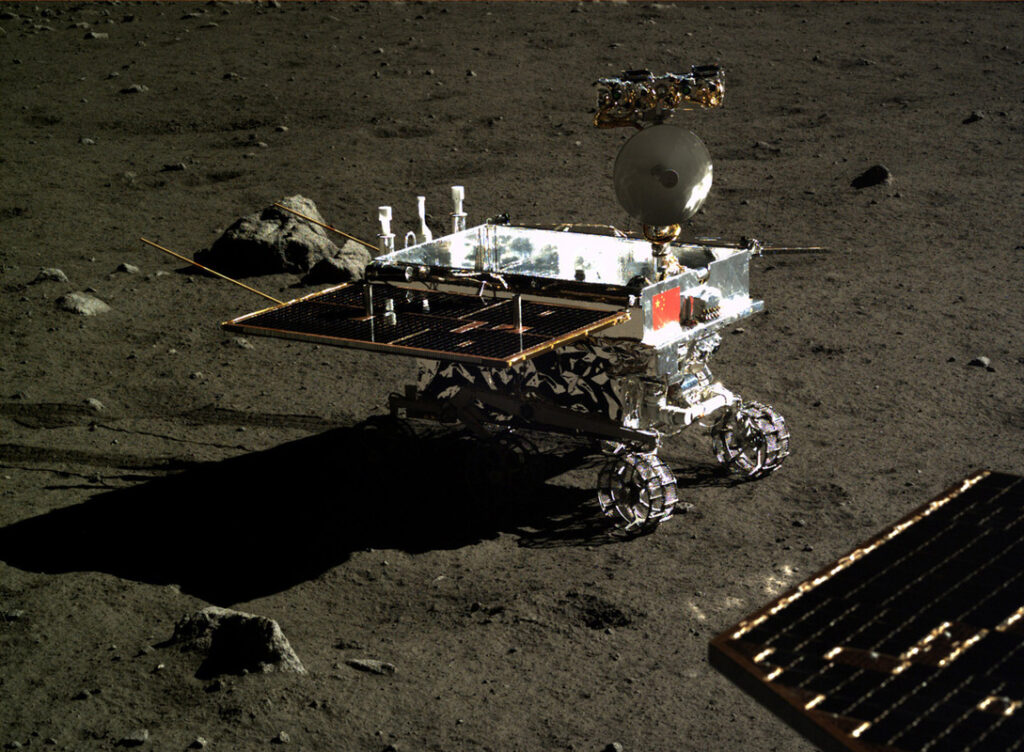

Chang’e-3 delivered not only a platform with scientific instruments to the lunar surface, but also a 140-kilogram Yutu, the first wheeled vehicle since Lunokhod-2. The nominal life of the base platform was one year, and that of the rover — three months. But actually they significantly exceeded the initial plan.

In 2018, radio amateurs still periodically intercepted signals from the Chanye-3 stationary platform. However, at that time only one operational instrument remained on board — the 150 mm optical telescope LUT, designed for imaging the sky in the near UV range. At the end of 2018, CNSA decided to stop the operation of the device to avoid the interference of radio signals that could complicate the landing procedure of the Chang’e-4 mission.

As for Yutu, it lost its mobility about 40 days after landing, so it also continued to work in a stationary mode. It last contacted with Earth in March 2015.

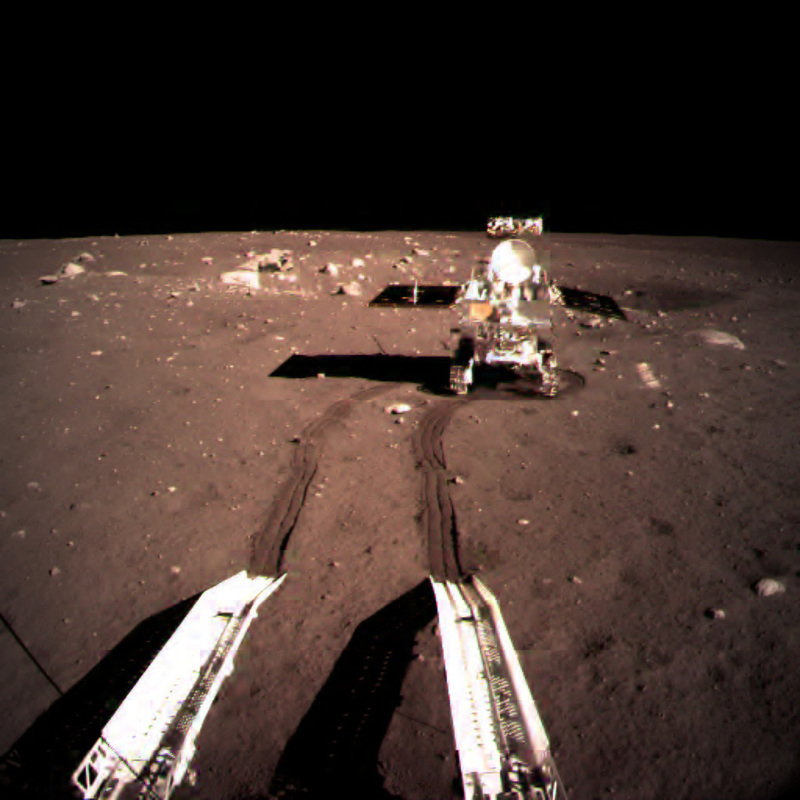

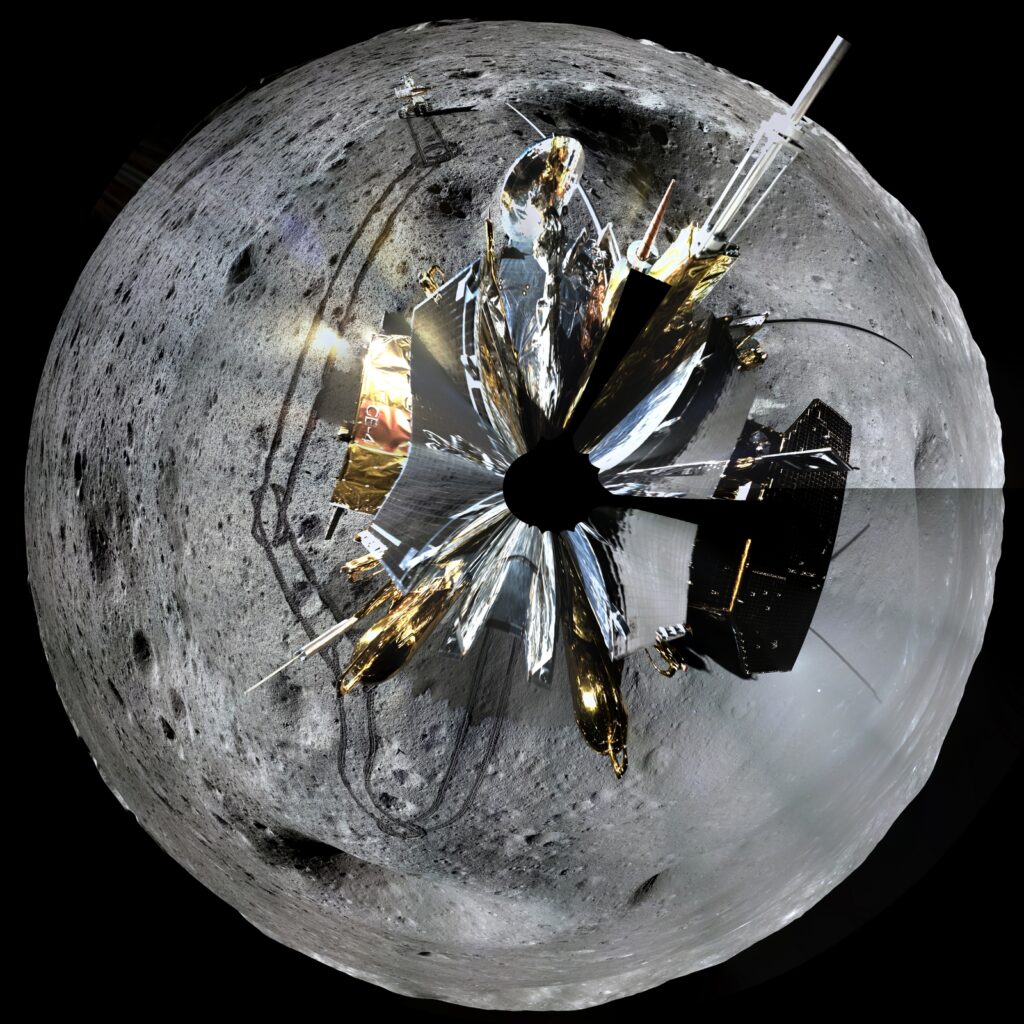

Initially, the start of the next landing mission Chang’e-4 with the rover Yutu-2 was planned for 2015. However, due to a series of delays and the need to make changes to the design of the device, it was delayed for as long as three years. The extremely high technical complexity of the mission, which required more careful preparation and launch of the relay satellite, also played a role. The thing is that Chan’e-4 was to be the first device in history to reach the far side of the Moon.

The main problem of such a landing is to ensure communication. This requires a special repeater in a halo orbit near the Lagrange point L2 of the Earth-Moon system. The device is in this position, would be able to see both our planet and the far side of the Moon at the same time. However, this required an additional launch, significantly increasing the total cost of the mission. It is for this reason, that NASA abandoned the plan to land one of the Apollo expeditions in the late 1960s.

But China was not afraid of additional expenses. In May 2018, CNSA sent the Queqiao repeater to the L2 point. Together with it, a pair of Longjiang microsatellites developed by scientists of Harbin Polytechnic University was launched. One of them never reached the Moon, but the other went into a selenocentric orbit. It operated successfully until July 2019, and then, like Chang’e-1, was deliberately crashed into the lunar surface.

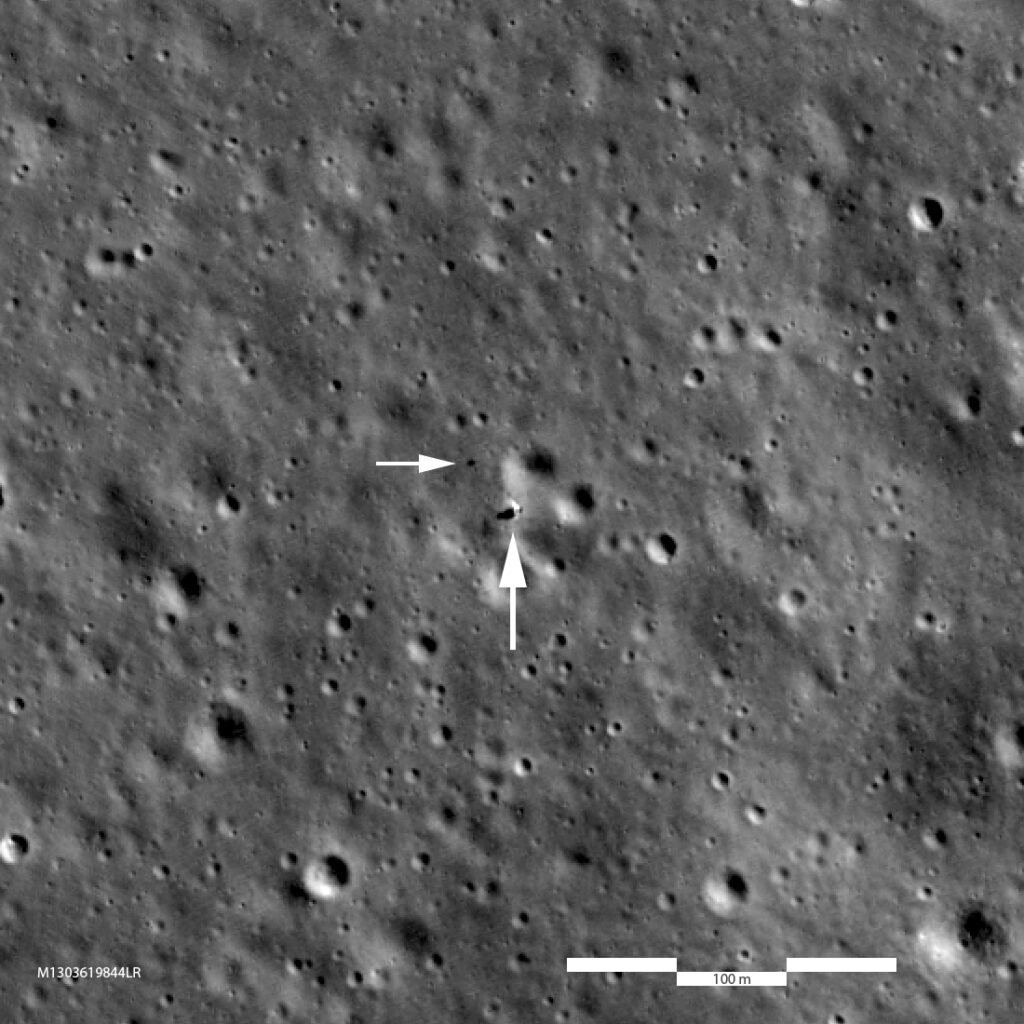

After the specialists received evidence of the successful operation of Queqiao, it was the turn of Chang’e-4 itself, which was launched on December 7, 2018. After 30 days, the device made a historic landing in the southern part of the Von Karman crater on the far side of the Moon. The success of this mission marked China’s transition from the phase of repeating old Soviet and American achievements to conquering new heights.

But Chang’e-4 entered the annals of world astronautics not only because of its landing place. In addition to traditional scientific equipment, there was a hermetically sealed aluminum container 18 cm high and 16 cm in diameter on board. It stored soil, seeds of cotton, potato, rapeseed, rhizomes, as well as yeast, drosophila and silkworm eggs. There were artificial lighting, devices for supplying water, air and nutrient solution inside the cylinder. The purpose of the experiment was to check the possibility of functioning of a closed ecosystem in conditions of reduced lunar gravity and a higher level of high-energy radiation.

According to Chinese experts, a few days after the landing of Chang’e-4, the camera installed inside the cylinder registered the germination of cotton seeds. This was the first time in history that a terrestrial plant had sprouted on other celestial body.

Chang’e-4 and Yutu-2 are still in operation. As of the beginning of July 2022, the rover has already traveled more than 770 meters on the lunar surface.

China is planning to fetch a piece of the moon

It is clear that the Celestial Empire is not going to stop there. Already at the end of this year, China will begin the implementation of the third phase of its lunar program. The Chang’e-5 robot is supposed to take a sample of the Moon’s substance and bring it to Earth.

It is worth noting that the path to the third phase took longer than expected. Back in 2014, CNSA launched the Chang’e-5T1 mission to test the technology for returning lunar material samples to Earth. The probe flew around the moon, then approached our planet and dropped a test capsule, which passed through the Earth’s atmosphere and landed on the territory of China.

The success of the test paved the way for the Chang’e-5 mission. Initially, its launch was planned for the end of 2017, but CNSA had to hastily adjust its plans due to last year’s Changzheng 5 launch vehicle accident.

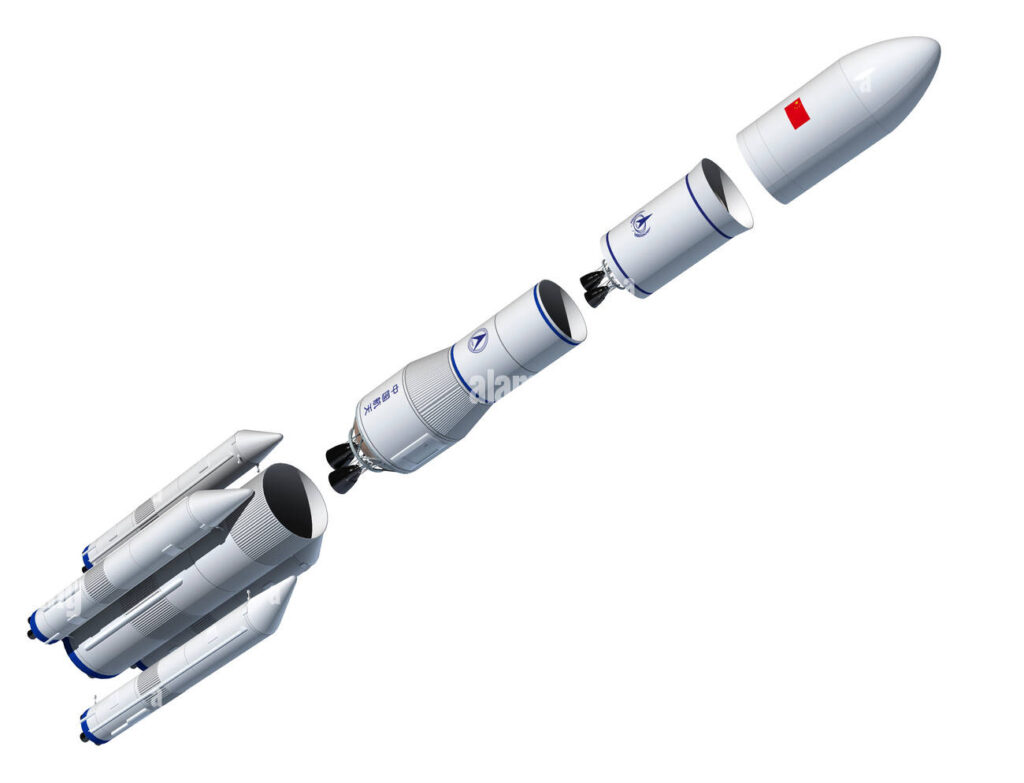

Up to this time, the lunar missions of the Celestial Empire were launched by rockets of the Changzheng-3 family. However, Chan’e-5 is much heavier than its predecessors: after all, it needs not just to land on the moon, but also to take off from its surface and return to Earth. Therefore, the spacecraft consists of four specialized modules (orbital, landing, take-off and returning), the total weight of which is almost four tons. Changzheng-3‘s cargo capacity is not enough to ensure sending such cargo to the moon. That is why Chinese experts developed new heavy missile Changzhen-5. However, its unexpected crash during the second launch showed that they had to make many changes to the design of the carrier. Only at the end of 2019, CNSA conducted successful launch of the updated rocket, which allowed resuming preparations for the Chang’e-5 mission.

Chang’e-5 went to the Moon in November 2020. The mission went off without a hitch. The lander made a successful landing near the Ryumker Mountains (a volcanic formation in the northwestern part of the visible side of the Moon) and took a soil sample, which was then “forwarded” to the return module. The capsule with samples landed in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region on December 16, 2020.

Subsequent analysis showed that the Chang’e-5 samples were formed no later than 2 billion years ago. Thus, they are much younger than the soil that was brought to Earth by Apollo expeditions and the Soviet Luna stations.

The future of the Chinese lunar program

The implementation of the Chang’e-5 mission marked the end of the third phase of the Chinese lunar program. This means that the Celestial Empire’s specialists are able to start working on its final stage.

Since China’s space industry is not quite transparent, we only know the most general details about the fourth phase so far. In 2023-2024, CNSA will likely launch the Chang’e-6 probe, which will land near the lunar South Pole and then return to Earth a sample of matter from this region. The choice of the landing site is not accidental: the south pole of the Moon is considered one of the most optimal locations for the creation of the first human settlement.

Following Chang’e-6, two more automatic probes will go to the moon. It is assumed that they will conduct a comprehensive study of the South Pole. The devices will look for deposits of valuable resources and possibly test some technologies that could be useful to the taikonauts during the construction of a lunar base.

The fact that the PRC plans to build a base on the Moon has not been a secret for a long time. Although the country’s authorities prefer to make as vague statements as possible on this issue, it is known that the Celestial Empire intends to create a settlement on the south pole of the satellite by the end of this decade or in the beginning of the next one. In 2021, the People’s Republic of China also signed a memorandum on cooperation in the creation of the International Scientific Lunar Station with Russia. However, the exact degree of Russia’s participation in the project is still unknown.

Anyway, Chinese engineers are already working hard to create equipment for the manned lunar program. Thus, in 2020, a successful test of a prototype of a new generation spacecraft took place. It was designed both for the delivery of teikonauts aboard an orbital station and for missions into deep space. It was launched into Earth orbit and performed a series of maneuvers that allowed it to raise its apogee to 8,000 km. Thanks to this the capsule of the ship entered the Earth’s atmosphere at a speed of about 9 km/c, which is significantly more than during normal flights in low Earth orbits (LEOs). This made it possible to test thermal protection in conditions similar to those that occur while returning to Earth from an interplanetary expedition. The new spacecraft will give China the opportunity to organize a manned flyby of the moon, like the American Apollo 8 expedition or the planned Artemis II mission. Such a flight could add prestige to the country.

But if we are talking about a mission with the landing of taikonauts on the moon, then only one ship is not enough. This requires a separate lander and a sufficiently powerful rocket capable of delivering it to our satellite.

The Changzheng-9 super-heavy rocket is being designed to become this carrier. The Chinese government approved plans for its creation in 2021. The rocket is planned to be used for manned missions to the moon, the assembly of various space structures, and also flights into deep space.

The initial concept of Changzheng-9 involved the creation of a classic disposable rocket, which has a three-stage design with the possibility of adding up to four side boosters to it. Then the project was revised. The rocket was left with side accelerators, and its first stage became reusable.

But apparently this is not the last metamorphosis of the vehicle. Recently it became known that Chinese engineers have developed a new project that involves the creation of a completely different, completely reusable rocket, the design of which is clearly inspired by Starship. It will consist of two stages operating on oxygen-methane fuel. The rocket will be able to deliver up to 150 tons to the low earth orbit and up to 50 tons to the flight path to the Moon. According to preliminary estimates, the first flight of the fully reusable Changzheng-9 may take place in 2035.

It is worth noting that, apparently, the leaders of the Chinese space program have not yet made a final choice in favor of any of the Changzheng-9 variants. But the general vector is quite clear.

The China’s plans to create an outpost on the Earth’s natural satellite raise a reasonable question about the possibility of a lunar race with the United States. After all, the south pole of the Moon is also the main goal of the American Artemis program. One can already imagine a situation when each of the parties tries to speed up the implementation of their plans in order to “take the best seats”. They can be both areas with the most easily accessible deposits of water ice, and “peaks of eternal light” — subpolar heights, almost constantly illuminated by the Sun, which makes them an ideal location for placing power plants.

In 2020, the United States and its space allies signed the Artemis Accords, a set of basic principles that should lay the foundation for international cooperation in the peaceful exploration of the Moon, Mars, comets, and asteroids. Among other things, it stipulates the possibility of creating the so-called “safety zones” in places where scientific and technical activities are carried out on the satellite. The agreement stipulates that states must respect each other’s “safety zones” and openly share all information to prevent conflict situations from arising.

At the moment, 21 countries, including Ukraine, have joined the Artemis Accords. However, it seems extremely unlikely that in the near future China will want to bind itself to some legal obligations with the USA. The two most powerful states on Earth actually do not cooperate in the space domain. And taking into account their far from the best political relations, as well as periodic mutual accusations (consider for example the recent statement of the head of NASA that China is going to capture the Moon), the situation is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

Of course, so far China has shown no haste in its lunar program. CNSA methodically followed the plans, and the country’s leadership did not try to hurry the organization, demanding at any cost to carry out the launch by some round date or for political reasons. Most likely, this played a large role in the overall success and safety of the Chang’e program. But further intensification of confrontation with the US may lead to a change in this approach. The Artemis Accords can also play its role. If the leadership of the People’s Republic of China perceives the proposal to create “safety zones” as an attempt to “divide” the Moon, we may indeed witness the beginning of a new lunar race.

But another option should not be ruled out. The moon could become not an “apple of discord”, but a point of contact for the two countries. When the US and China start creating bases at its south pole, they will have to work out the rules of engagement. Over time, this can give impetus to full-fledged cooperation and even the implementation of joint space projects. Who knows, maybe our night luminary is destined to become a kind of analogue of Soyuz- Apollo historic docking?