Scientists have used CHARA’s new array of antennas to explore Polaris. This giant luminosity belongs to a class of variable stars called Cepheid. Studies of the star have shown that it has a spotty surface.

Polaris research

Researchers using the Georgia State University’s Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array have discovered new details about Polaris’ size and appearance. The new study is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

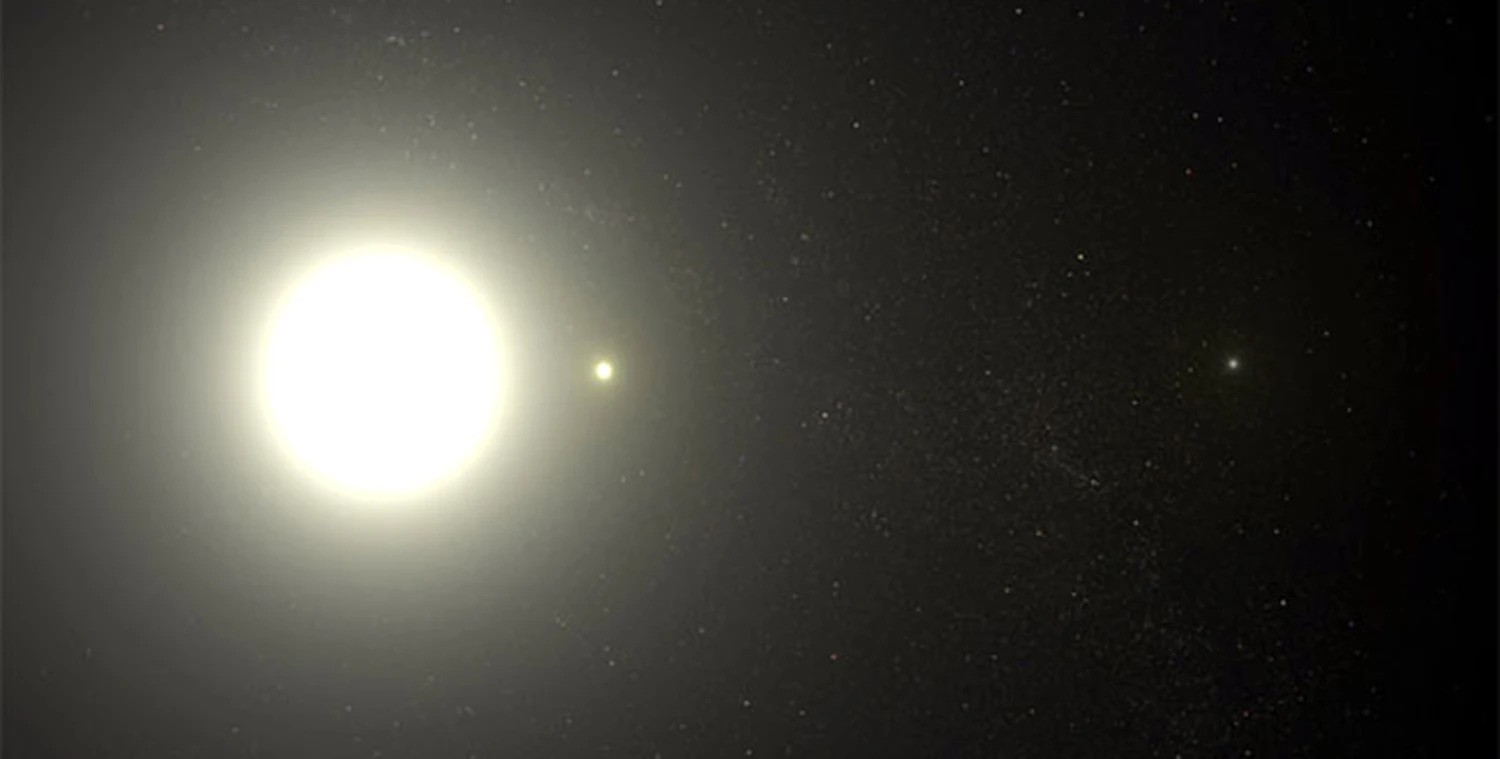

Earth’s North Pole points to the direction in space marked by Polaris. It is both a navigational instrument and an outstanding star in its own right. It is the brightest member of a triple star system and a pulsating variable star. The luminary periodically becomes brighter or fainter as its diameter grows and shrinks over the course of a four-day cycle.

Polaris belongs to a type of star known as a Cepheid. Astronomers use such luminaries as “standard candles” because their absolute stellar magnitude depends on their pulsation period: brighter ones pulsate more slowly than fainter ones. The brightness of a star in the sky depends on its absolute magnitude and the distance to the star. Since we know the true brightness of a Cepheid based on its pulsation period, astronomers can use them to measure distances to their host galaxies and to calculate the expansion rate of the Universe.

Motion of Polaris’ companion

A team of astronomers led by Nancy Evans at the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard and Smithsonian Institutes observed Polaris using the CHARA optical interferometer array of six telescopes at Mount Wilson, Calif. The purpose of the study was to map the orbit of a close, faint companion that orbits Polaris every 30 years.

“The small separation and large contrast in brightness between the two stars makes it extremely challenging to resolve the binary system during their closest approach,” Evans said.

The CHARA array combines the light from six telescopes located on top of the mountain at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory. By combining signals from them, the CHARA array can act as a 330-meter telescope to detect the faint companion as it passes close to Polaris. The observations of Polaris were recorded with the MIRC-X camera, built by astronomers at the University of Michigan and the University of Exeter in the UK. The MIRC-X camera has an excellent ability to capture details of stellar surfaces.

Polaris surface features

The team successfully tracked the orbit of the nearby companion and measured changes in the Cepheid’s size during its pulsation. The analysis showed that Polaris has a mass five times greater than the solar mass, and its diameter is 46 times greater than our luminary.

The biggest surprise was the view of Polaris in close-up images. The CHARA observations gave the first insight of the surface of the variable Cepheid.

“The CHARA images revealed large bright and dark spots on the surface of Polaris that changed over time,” said Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array. The presence of spots and the rotation of the star may be related to the 120-day variation in the measured velocity.

Astronomers plan to continue imaging Polaris in the future. They hope to better understand the mechanism that generates the spots on its surface.

According to phys.org