Beta Persei, known as Algol, gets its name from an Arabic word referring to demonic beings that dwelled in burial grounds. The star earned it due to the variable nature of its brightness. Yet, the story of young astronomer John Goodricke, who unraveled the mystery of Algol, is equally remarkable.

John Goodricke

September 17 marks the 260th anniversary of John Goodricke’s birth. Known for his work with variable stars, Goodricke lived a life both remarkable and tragic. Born in 1764 in Groningen, Netherlands, he was the son of British diplomat Baron Henry Goodricke and a Dutch merchant’s daughter.

At the age of five, Goodricke contracted scarlet fever and completely lost his hearing as a result. In the 18th century, this was a dire thing indeed, even for children of nobility. Deaf children often faced significant challenges in education and society, and were frequently misunderstood or unfairly labeled as mentally impaired.

Fortunately for John, he was able to attend one of the world’s first schools for deaf and mute children in Edinburgh, founded by Thomas Braidwood, a pioneer in sign language development. Thanks to Braidwood’s efforts, John learned to speak and read lips fluently and received a strong education. This allowed him to enter Warrington Academy, which was renowned for its programs in natural and exact sciences. It’s there that his fascination with stars first took hold.

In 1781, after completing his studies, Goodricke moved back with his family, as his father had returned to England to pursue a political career. And once again, John was fortunate. His new neighbor, Edward Pigott, who was thirteen years his senior and, as is often the case with nobility, a distant cousin. More importantly, Pigott had his own observatory and was an accomplished astronomer along with his father.

Algol

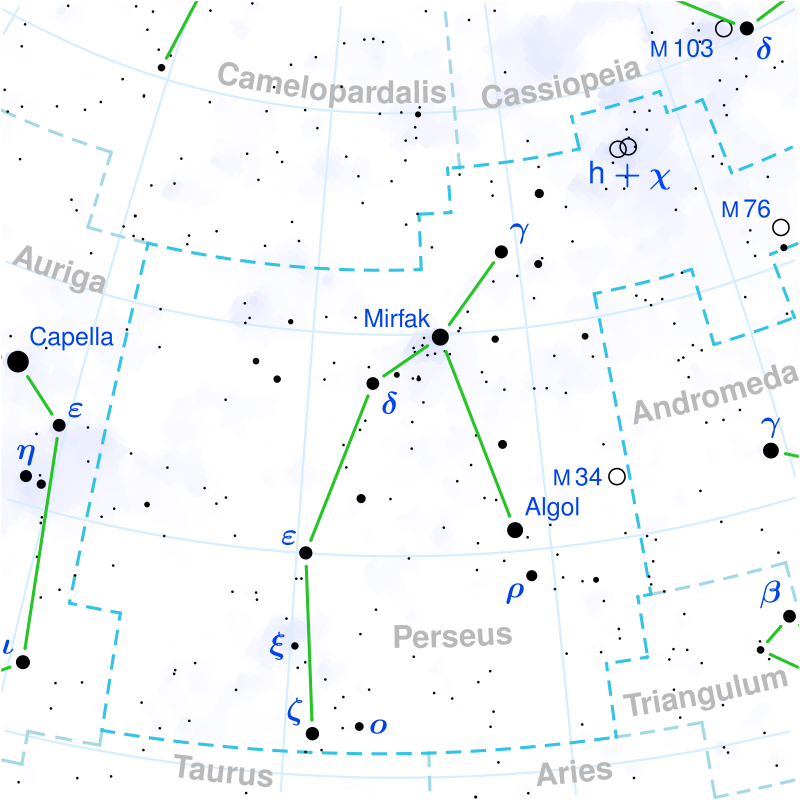

John began spending more time at Pigott’s observatory, where he first made a fascinating discovery concerning Beta Persei, also known as Algol. Over several nights, he noticed that the star’s brightness changed.

Goodricke was meticulous in his observations and soon determined that the star’s brightness oscillated with a period of 2.87 days, with two distinct dimming phases—one weaker and one stronger. This variability was unusual. After all, stars were generally thought to be constant. He shared his findings with Pigott, who informed him that Beta Perseus’s periodicity was known and had been observed for many centuries.

Even the name Algol comes from the Arabic al-ghūl, referring to a mythical demonic being or shape-shifter that preys on humans. Beta Perseus did indeed have a reputation as the Demon Star, but in the decades leading up to Goodricke’s observations, astronomers had identified several other stars with similar fascinating properties.

Goodricke was deeply intrigued by the phenomenon and soon came up with an explanation. With Pigott’s support, he presented his findings to the Scientific Society of London. While it’s unclear what the esteemed scientists expected from an eighteen-year-old with deafness, Goodricke delivered a solid hypothesis that explained the nature of the Demon Star. He proposed two possibilities: either a large dark object was orbiting and blocking the star’s light, or the star had hemispheres with contrasting temperatures—one hotter and one cooler—and we see them alternating as the star rotates.

Scientists were so impressed by Goodricke’s explanation that they awarded him the prestigious Copley Medal. He continued to explore the night sky, working alongside Pigott.

The nature of Algol

Goodricke continued his search for variable stars and studied Beta Lyra, also known as Sheliak. He found that its brightness varied over a period of 12.9 days, showing a curve with two nearly identical dips. In 1784, he discovered that Delta Cephei varied over 5 days and 9 hours, but its luminosity pattern was different, featuring a single peak that rose quickly and fell more slowly. This indicated a different type of variability. Around the same time, Pigott found that Eta Aquilae displayed similar behavior.

On April 16, 1786, the London Scientific Society elected Goodricke as a member at just 21 years of age. Sadly, he never learned of this honor. His health had been declining due to constant observations in the cold, which eventually led to pneumonia. John Goodricke passed away on April 20, 1786.

But he was never forgotten. In the 20th century, a college at the University of York, where he conducted his research, was named in his honor, and even an asteroid bears his name. Yet, it was his pioneering work that truly cemented his legacy.

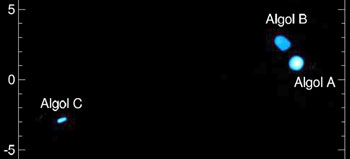

Today, we know Goodricke was entirely correct about Algol. This three-star system is 94 light-years away, with the smallest star orbiting the central pair every 680 days, though it doesn’t contribute much to the Demon Star’s unusual behavior.

The other two stars, however, are quite interesting. The first, Algol A, is a blue giant, 3.17 times more massive and 182 times brighter than the Sun. The second, Algol B, is a small red giant, with only 70% of the Sun’s mass, but its diameter is one and a half times larger than the Algol A.

Algol B’s luminosity is only seven times that of the Sun, making it twenty-six times dimmer than Algol A. The two stars orbit each other at a distance of roughly 6.8 million miles. When the red giant, Algol B, passes between us and Algol A, we observe the steeper dip in the Demon Star’s brightness, just as Goodricke predicted. Conversely, when the stars swap places, we see the smaller dip.

Then in the 20th century, the Demon Star posed a new puzzle for astronomers, one that Goodricke couldn’t have predicted. Algol A and B should have formed at the same time, and by the rules of stellar evolution, the more massive star should have aged first, turning into a red giant. Yet, Algol A remained hot and blue, while its lighter companion, Algol B, had already aged.

This became known as the Algol paradox, but it wouldn’t remain a mystery for long. The proximity of the two stars was the key. Initially, Algol B was the more massive star, but as it became a red giant, its outer layers were pulled toward Algol A, increasing its mass and temperature. This mass transfer explains the unusual configuration we see today.

The world of variable stars

Goodricke and Pigott’s work paved the way for a new field of astronomy: the study of variable stars. It became evident that Algol was just one of many Demon Stars in the universe. In fact, systems like Beta Persei are only one type of eclipsing variable stars among countless others.

Another example is Beta Lyra, which Goodricke also studied. In this multiple-star system, the close orbit of the two main stars creates the unusual phenomena he observed. They are so close that a “bridge” of matter has formed between them.

Delta Cephei proved to be even more intriguing with its unique brightness variation. It pulsates, periodically expanding and contracting. Stars like Delta Cephei are known as Cepheids. They share a key feature: their pulsation period is directly related to their luminosity.

This connection allows astronomers to determine a Cepheid’s luminosity and, consequently, its distance from us. Their brightness is so intense that they can be observed in other galaxies, making them crucial for measuring the distances to these distant “island universes.”

John Goodricke’s life was brief and filled with challenges. While it’s impossible to know what further discoveries he might have made had illness not taken him so early, his achievements, including unraveling the mystery of the Demon Star, ensure his legacy endures through time.