Scientists have long known that some rocks on the surface of the Moon contain titanium. But how much of it is really there, and is it easy to mine? A new study has tried to answer this question.

Valuable resource on the Moon

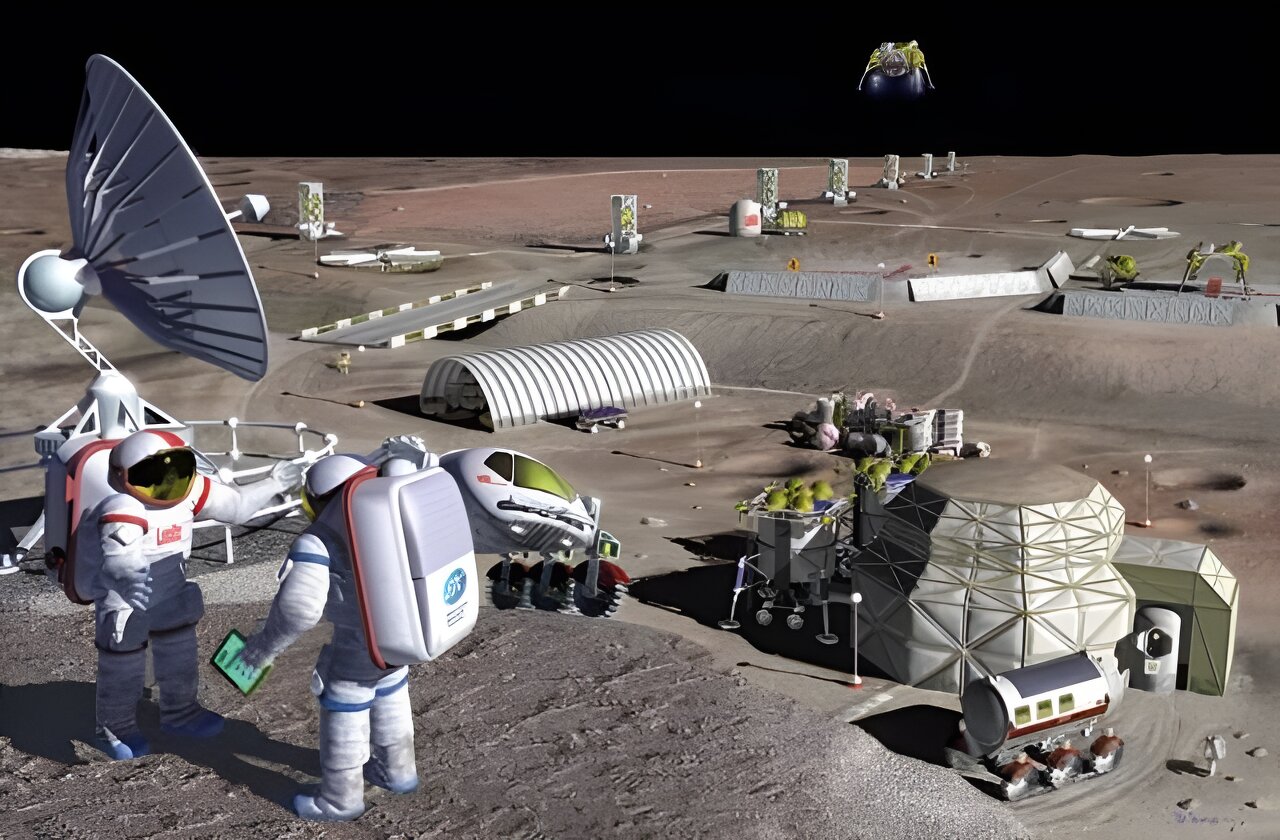

The exploration of the Moon for its resources is an important step in humanity’s journey toward exploration of the Solar System. One of the most common resources on it is considered relatively valuable also on Earth — titanium.

At $10,000 per ton, it is one of the most valuable metals used in various industries such as aerospace and nanotechnology. Can we use titanium from the Moon to provide Earth’s economy with more of this valuable material? This question is the main focus of researchers from Finland’s Uppsala University.

Not surprisingly, titanium, the ninth most abundant element in the Universe, is abundant on the Moon. Most lunar titanium is found in a mineral called ilmenite, which is also available on Earth for about $390 per metric ton. Ilmenite represents up to 20% of the volume of some rocks in the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo astronauts landed and collected samples.

Titanium mining on Earth and on the Moon

To ensure the accuracy of the allowable amount of potential titanium available on the Moon, the authors of a new study published in the journal European Geologist, Renaud Merle, Mikael Höök, Valentin Troll, and Alexander Giegling, examined two different concentrations of ilmenite — 3% for the total regolith in the area and 15% for the basaltic rocks that Apollo astronauts sampled. Next, they compared the potential productivity of a mine in the region to the Tellnes mine in their native Norway, one of the most productive in the world.

Tellnes is located on one of the richest titanium deposits in the world, with reserves estimated at 575 million metric tonnes available for mining. Although its size dwarfs the scale of the Sea of Tranquility, its high concentration of 18% of TiO2 (titanium dioxide is the most common form of the material) means that it is probably highly mined over its lifetime and is a baseline for comparison with the mine’s monthly production. Importantly, it regularly produces 750 kilotons of ilmenite per year, which is about 5% of the world’s titanium production.

A large excavator and six large dump trucks are required to operate the mine. In total, the Caterpillar-built excavator and dump trucks represent nearly 2,500 tonnes of material that will be sent to the Moon. The authors estimate that it would take more than 40 launches of the Saturn V rocket — about as many as it took to completely build the ISS.

Efficiency of mineral extraction on the Moon

After the equipment is on the Moon, it will still need to be powered. The large diesel engines that now power these giant machines are not well adapted to the Moon. The total power required on Earth to run all seven machines is about 11 MW, which the authors believe can be met by a combination of solar and nuclear power. However, they don’t mention how a large enough battery would affect their weight calculations.

So, how effective would such an extractive operation be if everything was in place and operating? There are several ways to measure efficiency, but first, let’s examine the total amount of titanium mined. The authors calculate that the expected production is about 500,000 tonnes per year — about 2/3 of Tellnes’ production, but it should be noted that it will take up to 20 years to reach this level.

A lot can change in 20 years from a technological and material use perspective in general, so, finally, this article doesn’t make a compelling argument for titanium mining as an economic solution, especially since mines on Earth can quickly ramp up production to meet the growing terrestrial demand for it.

Prospects for titanium mining on the Moon

However, the mining process has the additional benefit that splitting ilmenite to release titanium also releases the oxygen needed for everything from rocket fuel to the air we breathe. Consequently, instead of looking specifically for titanium, early developments on the Moon could focus on the oxygen contained in ilmenite, and mine titanium, probably the more valuable of the two materials on Earth, as a side effect.

However, as the authors of the article point out, it is doubtful that any such project will be realised in the next 10 years. By that time, technology will continue to advance until one day someone mines the first titanium on the Moon. It remains to be determined where this valuable material will be most useful when this happens.

According to phys.org