When reading the news about another NASA rover successfully arriving on Mars, we’ve started to forget how complex a target the Red Planet really is. Nearly 50 missions have been launched to it during the space age. Only 20 of them have fully accomplished their tasks.

Regarding others, some missions were partially successful (for example, when the landing vehicle was lost but the orbiter achieved its objectives) and some ended in complete failure. We’ll talk about the most talked-about Martian failures and what they taught space hardware designers.

14.5 seconds of Mars 3

The history of Soviet attempts to explore Mars will give odds to any Shakespearean in terms of drama. The USSR tried to send a messenger to the Red Planet at the dawn of the space age. Considering the low reliability of the rockets of that time and the general imperfection of technology, there is no reason to be surprised by the results. Of the eight Soviet vehicles launched in the 1960s, only two managed to leave the vicinity of Earth — and both failed long before meeting their target.

In the 1970s, the USSR made a new, much more ambitious attempt to reach Mars. Then the task was not just to reach the planet, but also to land on it. The closest to its implementation came the Mars-3 spacecraft — on December 2, 1971, its landing vehicle entered the atmosphere of the Red Planet. At the stage of its descent, a rather complex scheme was used, involving a combination of parachutes, braking engines and a separate system that diverted the parachute container with the engine away from the vehicle (the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers subsequently landed according to a similar scheme).

And Mars 3 did succeed. The spacecraft was able to make a soft landing on a neighboring planet. Next, it attempted to begin transmitting the first-ever panorama of the Martian surface, but just 14.5 seconds after the session began, it went silent forever. The Mission Control Center (MCC) received only a mess of black and white stripes that made it impossible to see anything. What really happened to the vehicle, experts still can’t say.

This fiasco stands out against the background of other Martian failures of the USSR in that Mars-3 remained the highest point of achievement of the Soviet program to explore the Red Planet. Subsequently, vehicles built by this country have no longer been able to make a soft landing on Mars.

Swan song of the Soviet space program

Well, Mars has become a real graveyard for Soviet space technology. None of the missions launched to it in the 1960s and 1970s managed to perform all the tasks assigned to it (the greatest achievement was the Mars-5 spacecraft, which worked for two weeks in an areocentric orbit). In the late 1980s, the USSR made a new and, as it became clear later, the last attempt in its history to overcome this trend, betting on a pair of probes “Phobos”, which had an identical design.

As of that time, they were the largest and most massive vehicles ever sent into interplanetary space. They were supposed to carry out a highly ambitious program to explore Mars and land small probes on the surface of its moon Phobos, after which they were named.

However, less than two months after the launch, the MCC lost contact with the Phobos-1 spacecraft. Attempts to re-establish communication were unsuccessful. During further analysis of the flights, it was established that this was due to an error in the computer program that was responsible for controlling the probe — one of the operators simply missed one character in it. That was enough to ruin a very expensive vehicle.

At the same time, Phobos-2, despite a number of failures and malfunctions during the flight, still managed to reach the Red Planet and even perform the first stage of its scientific program. But when the spacecraft was about to drop landing probes on Phobos, communication with it was suddenly interrupted, and attempts to restore it were unsuccessful. Phobos-2 is believed to have malfunctioned due to a failure of the onboard computer, although some ufologists have traditionally blamed it on Martian intrigue.

Mysterious disappearance of Mars Observer

If the USSR’s Martian program as a whole can be considered a failure, in the case of NASA everything was exactly the opposite. Of course, the U.S. Aerospace Administration also lost a few Martian probes, but in general, the 60-80s of the last century were quite successful for it in the study of the Red Planet.

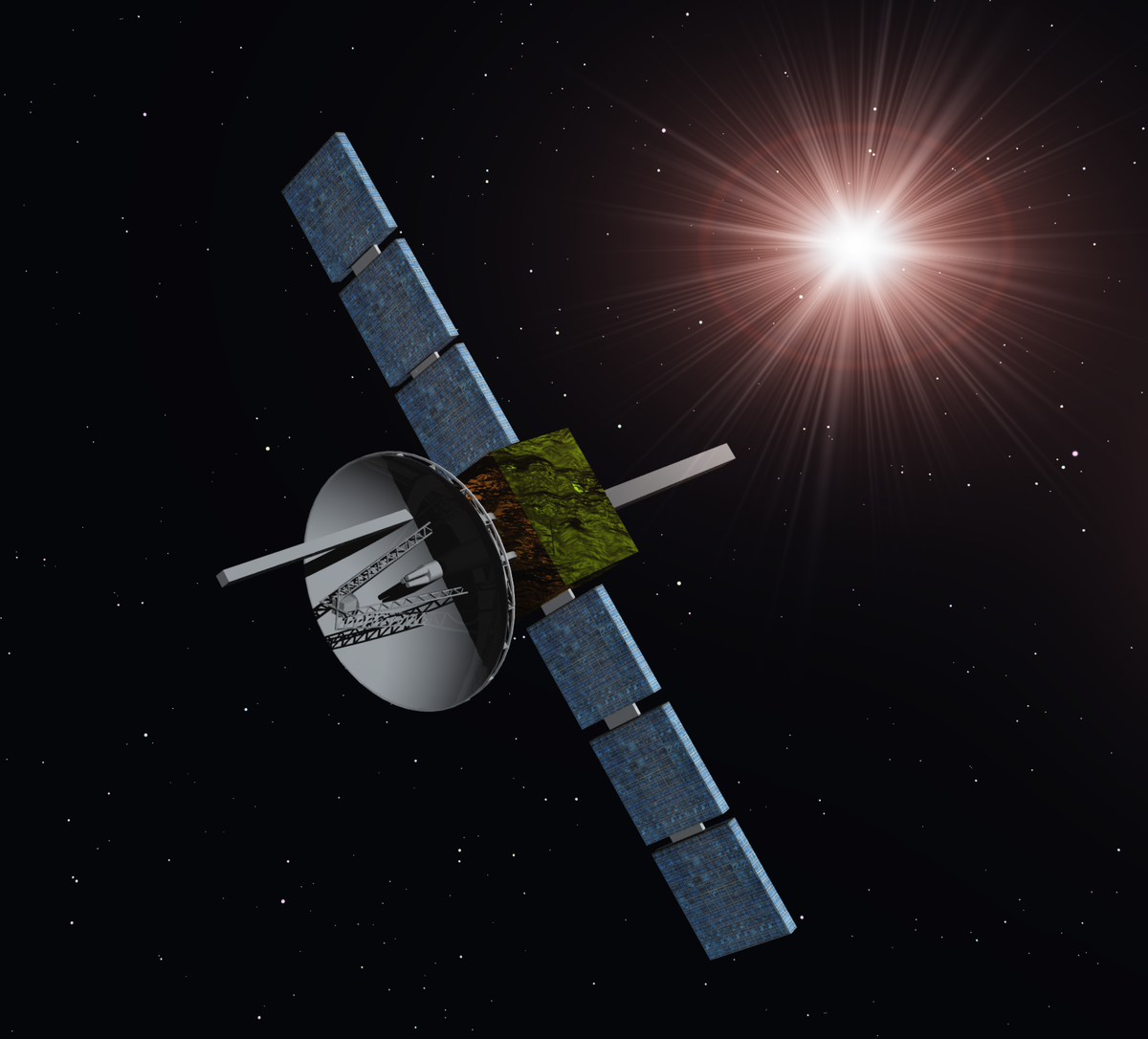

However, NASA’s luck ran out in the 1990s. In 1992, the organization launched the very expensive Mars Observer, which was supposed to study the Martian climate and atmosphere. However, just three days before entering orbit around the planet, it suddenly silenced.

Despite the engineers’ desperate attempts to re-establish contact with the spacecraft, Mars Observer never made contact again. What exactly happened to it is still a mystery. According to the most popular assumption, its engine exploded. Whether this is true or not, we are unlikely to find out.

The mysterious disappearance of Mars Observer was a painful hit to NASA’s reputation, and it is still not forgotten. As many engineers and designers of interplanetary technology admit, cases of sudden loss of communication with spacecraft still give them very unpleasant flashbacks and fears that their brainchild may share the fate of Mars Observer.

Pacific odyssey of the Russian space program

In 1996, Russia tried to prove to the world that rumors of the imminent death of its space program were greatly exaggerated and that it was a “worthy successor” to the Soviet Union. The task was assigned to the Mars 96 mission. The seven-ton vehicle, which was a record for interplanetary missions at that time, was to enter orbit around the Red Planet, study its surface and atmosphere, and drop a pair of small landing modules and penetrator probes.

Before the launch, the developers of Mars-96 swore that they had taken into account all the mistakes of the Phobos. At the same time, given the chronic problems with funding, as well as the rather sad experience of Soviet missions to Mars, many independent experts were skeptical about the prospects of the project and didn’t rate its chances of success very highly. Eventually, it happened. The spacecraft didn’t even manage to escape beyond the Earth’s gravitational sphere. Due to a booster failure, it remained in low orbit and entered the atmosphere after a few rotations.

Interestingly, the exact location of the Mars-96 crash hasn’t been determined yet. At first it was thought that its unburned debris (particularly radioisotope thermoelectric generators containing plutonium-238) had fallen into the Pacific Ocean. Later there were eyewitness reports that some fragments of the probe could have reached South America. However, since they were never found, it is probably just a legend.

Japan’s failed debut

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Japan was perceived by many in the West as the next superpower. Its economy was growing like mad, and it actively conquered new areas, including space. These efforts culminated in the Nozomi mission, which targeted Mars. If successful, Japan would become the third country in history (after the US and the USSR) to explore the Red Planet with a spacecraft.

Nozomi was launched in July 1998. However, as the power of the Japanese rocket wasn’t enough to directly send the spacecraft to Mars, it had to perform a series of rather graceful gravitational maneuvers near the Moon and the Earth for additional acceleration. Unfortunately, the operation went awry, and the Nozomi didn’t reach its intended orbit.

At the cost of enormous efforts of engineers and significant fuel consumptions, the spacecraft still managed to direct to a new trajectory, providing the arrival to the Red Planet in 2003. But during the flight, Nozomi was hit by a powerful solar flare that disabled the fuel heating system. By the time the probe reached Mars, the hydrazine in its propulsion system had frozen. The space traveler failed to perform the required maneuver and simply flew past the planet. Since then, Japan has never launched its spacecraft to the Red Planet.

NASA’s Double Failure

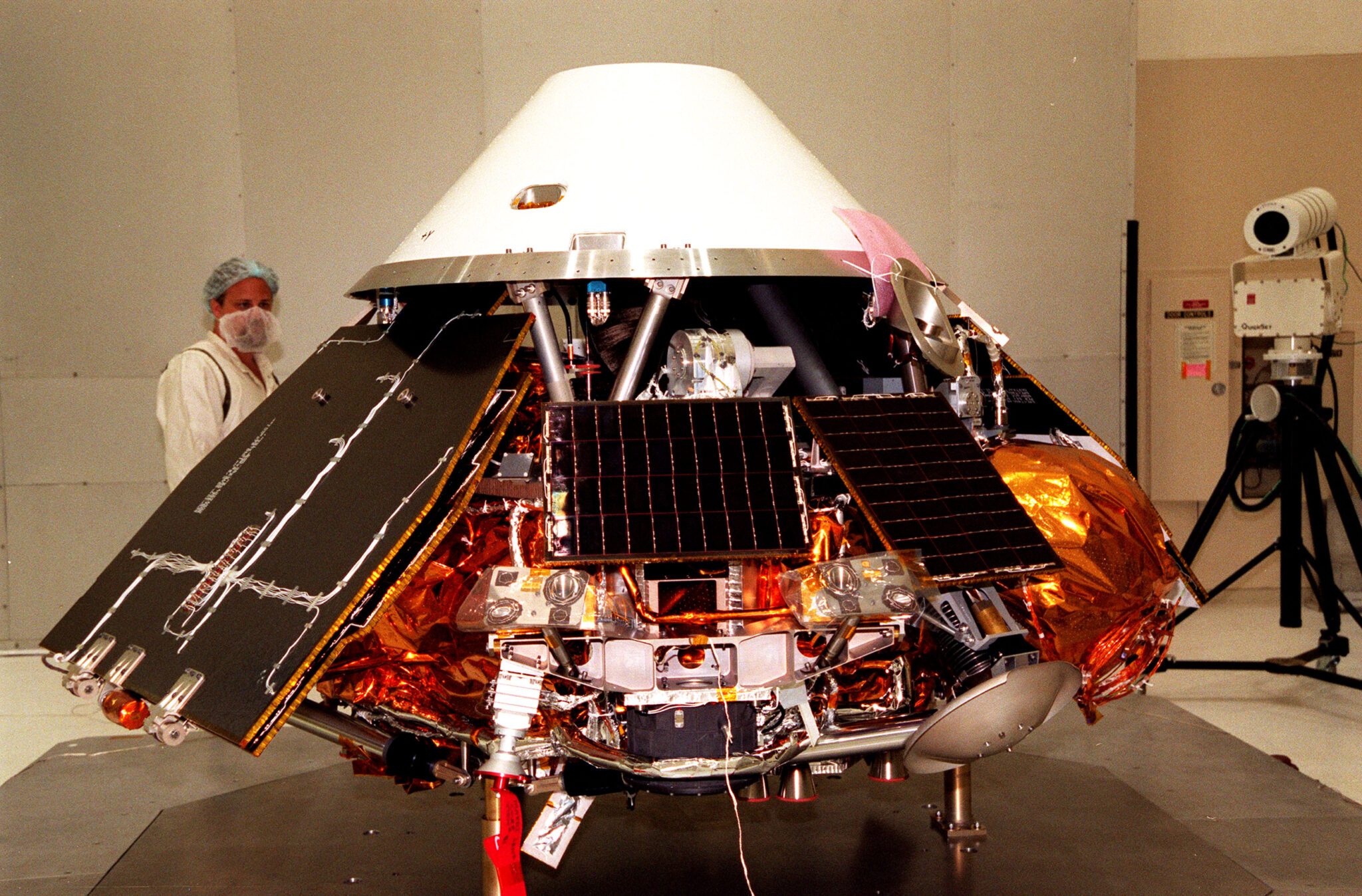

The year 1999 was to be marked by the conquest of Mars for NASA. In September, the Mars Climate Orbiter (MCO) was scheduled to enter orbit around the planet. It was to do climate research and also serve as a relay for the Mars Polar Lander mission, scheduled to arrive in December of that year. It was tasked with making the first-ever landing at the edge of the southern Martian polar cap and focusing on the search for water ice.

On September 23, MCO began a braking maneuver that would put it into an areocentric orbit. Quite quickly it became clear: something had gone wrong. Communication with the spacecraft was interrupted earlier than planned, and it could not be restored.

Further analysis of the data showed that the MCO flight path was not as planned. The spacecraft passed at a distance of only 57 kilometers from the planet’s surface and most likely burned up in its atmosphere. The investigation determined that such a serious error was caused by a mismatch between the two measurement systems. The ground computer software used the British unit of measurement (pound-force), while the probe’s on-board computer used metric newtons. This fatal contradiction caused it to deviate from its intended course. It was mostly because of this accident that NASA decided a few years later to switch completely to the metric system to avoid repeating such ridiculous mistakes.

Mars Polar Lander suffered a similar fate, after entering the atmosphere, it was permanently silenced. According to experts, it was probably damaged by a software error. According to the most popular version, when the vehicle released the landing legs, vibrations occurred in its body, which the onboard computer perceived as touching the surface. As a result, the probe prematurely shut off its engine and crashed.

Pacific odyssey of the Russian space program (part 2)

In 2011, Russia once again tried to demonstrate to the world that it is a great space power and is capable of more than eating up the Soviet legacy. Mars, or rather its largest moon Phobos, was again chosen as the target.

The inglorious fiasco of Mars-96 didn’t teach the designers anything. Instead of trying to build a relatively simple and inexpensive probe that could be used to gain experience and practice technology, they again built a monstrous and highly complex vehicle called Phobos-Grunt. It was assigned an even more ambitious goal than last time, it was to deliver a sample of Phobos’ matter to Earth.

It is difficult to say now about what the designers had in their heads when they decided that after all the past failures they could solve the problem of such a scale. The combination of excessive ambition and poor reliability led to a logical repetition of the history of 15 years ago. Like Mars-96, Phobos-Grunt encountered booster failure, got stuck in Earth orbit, and eventually joined Russia’s “Pacific space constellation.” Together with it, the first Chinese probe for the study of the Red Planet “Inho-1” died.

If the failure of Mars-96 could still be blamed on the “chaotic 1990s”, the Phobos-Grunt clearly showed the whole world that it was not simply about money, but about the degradation of the Russian space industry, unable to repeat the Soviet successes. Although even then some Russian officials tried to blame the failure on Western intrigues and sabotage. But this didn’t help much. The demonstration was so convincing that countries such as China and India, which had previously planned joint interplanetary missions with Russia, subsequently abandoned such intentions. As further events showed, it was absolutely the right decision.

Hard landing for ESA

Since its existence, the European Space Agency (ESA) has sent two missions to Mars. Both followed the same script. While the orbiter successfully accomplished all of its tasks and is still operational, the attempt to make a soft landing on Mars ended in an unfortunate fiasco.

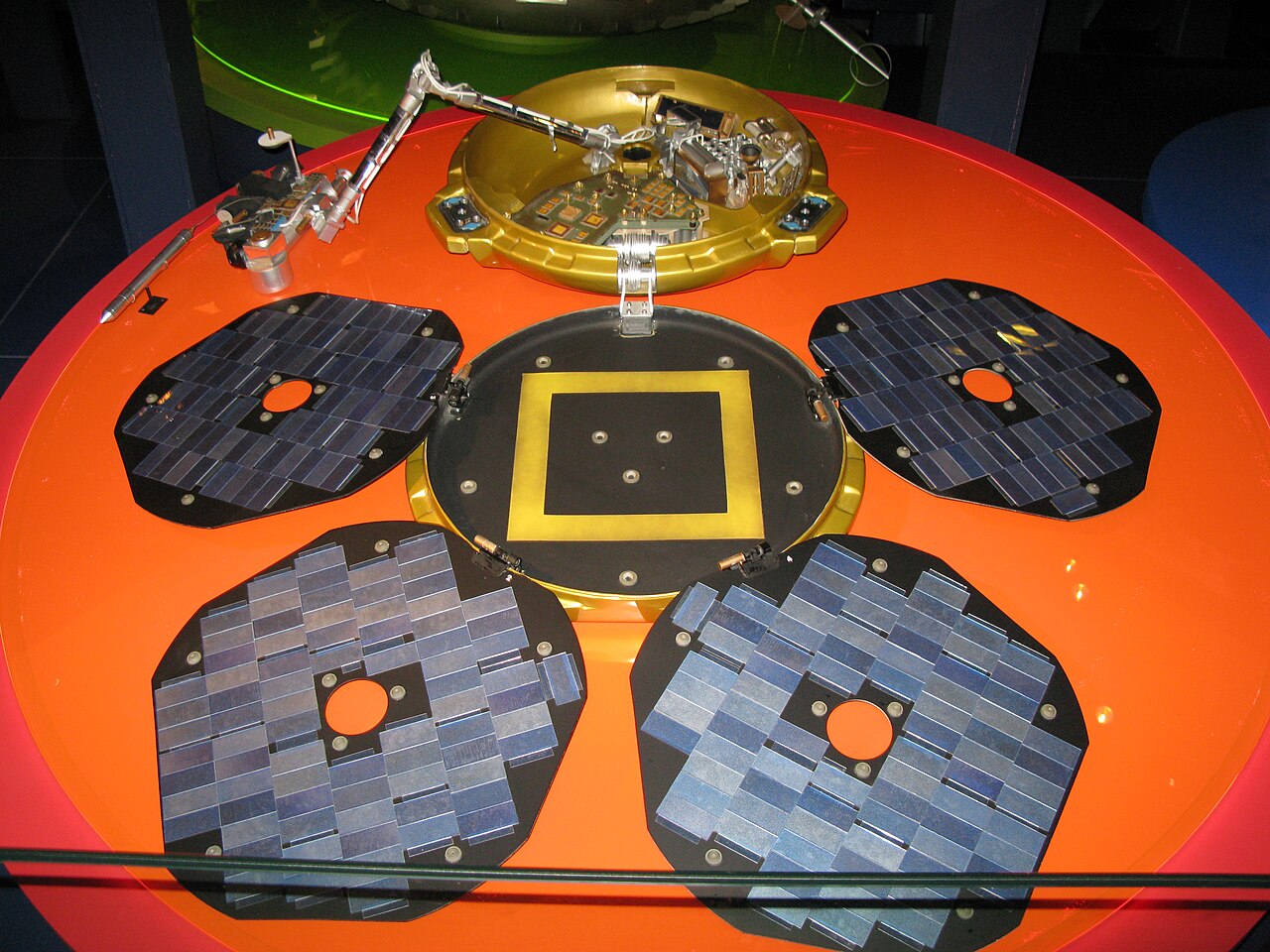

ESA first decided to conquer Mars in the early noughties. This task was given to the Beagle 2 probe. It separated from the Mars Express spacecraft and began its descent on December 25, 2003. The European control center correctly received telemetry until the moment of landing, after which the automatic scout was silent and didn’t contact any more.

The mystery of Beagle 2’s death was only solved in 2015, when the MRO spacecraft finally managed to find and photograph its landing site. The reason was extremely disappointing for everyone involved in the project. Turns out the landing itself was a success. But after it, one of the amortizing airbags deflated incompletely, depriving the probe of the ability to deploy solar panels and an antenna to communicate with Earth.

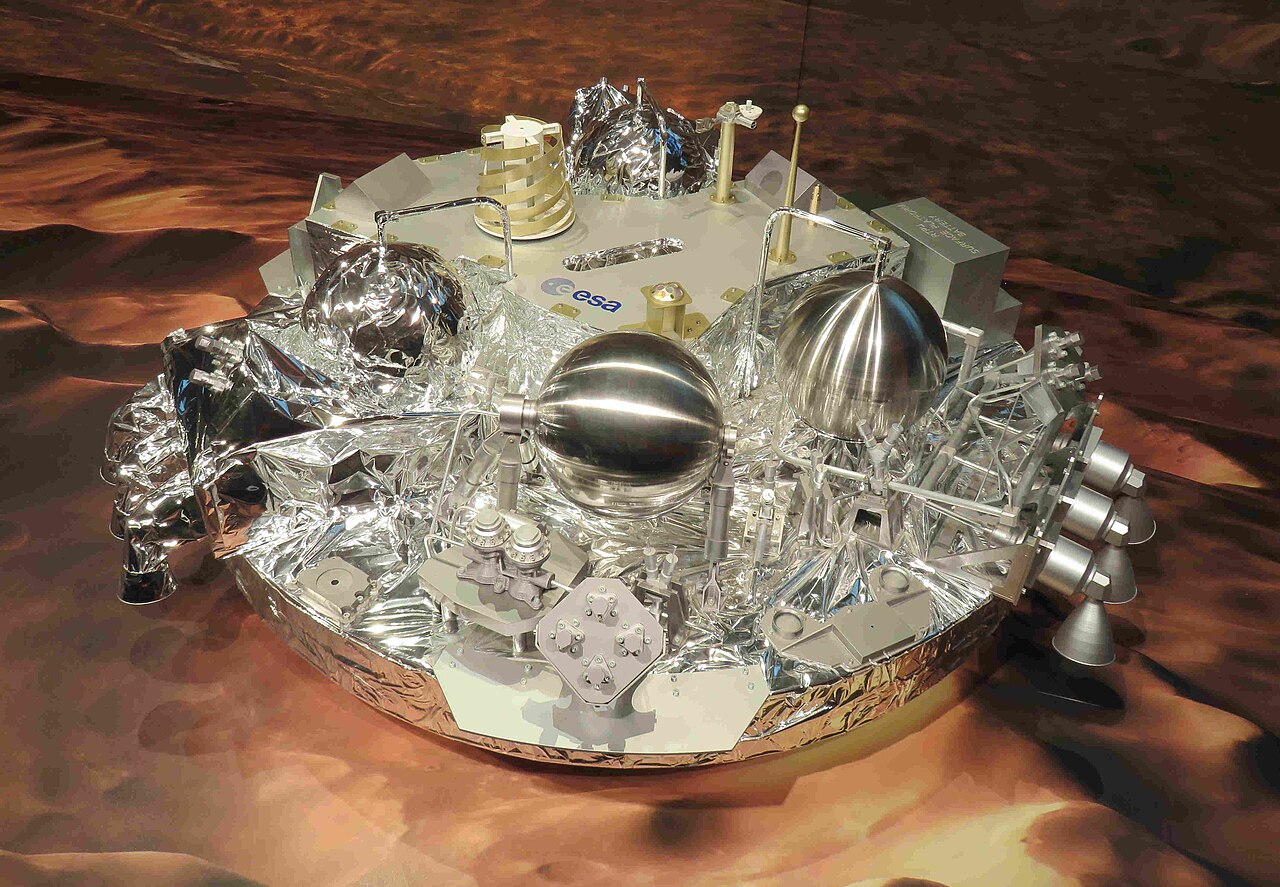

History repeated in 2016. This time ESA sent the Schiaparelli landing module to the Red Planet. It was part of the TGO mission and was to practice re-entry technology and demonstrate Europa’s ability to deliver cargo to the surface of Mars. If the module was quite successful with the first part of the program, the second part was not. Fifty seconds before landing, the MCC lost its signal. A few days later, the same MRO photographed the crater formed at the Schiaparelli crash site.

Further investigation determined that, due to a malfunction in the inertial measurement unit, the module had incorrectly determined its altitude and prematurely released its parachute, after which it briefly activated and then deactivated the landing engines. At the time of their shutdown, Schiaparelli was still at an altitude of 3.7 km. Therefore, it fell to the surface at a speed of about 540 km/s.

All the above events could have been safely avoided if a procedure for checking for obvious errors had been built into the module software. In addition, the malfunction was fairly easily detected during additional inspections. However, for some mysterious reason, the mission’s programmers failed to carry them out, which led to a very unfortunate accident.