Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) is expected to be visible to the naked eye by mid-October and is predicted to have the brightest tail of 2024. While the best view in Europe and the United States is expected around October 13, it’s worth trying to spot it earlier, wherever you are. Let’s dive into how to catch it and why this hunt can pose such a challenge.

Approaching the Sun: what happens to the comet near perihelion

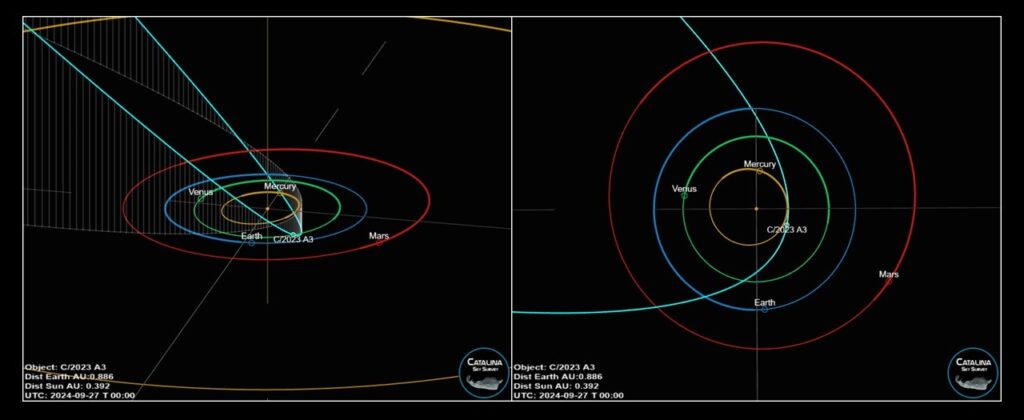

The most anticipated comet of 2024 is about to approach its closest point to the Sun. On September 27, at 1:47 PM Eastern Time, C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) will race through perihelion at a stunning 42 miles per second. In Europe, this will occur around 7:47 PM CEST. Current observations suggest the comet originated from the distant Oort Cloud and is making its first approach to the Sun. This means that its nucleus is being exposed to intense solar radiation for the first time in billions of years.

The nucleus of C/2023 A3 is estimated to be just 1–2 kilometers, or up to 1.2 miles, in size. It’s the only solid part of the comet, but it’s responsible for the entire range of phenomena we observe as it approaches the Sun. On September 27, the tailed visitor will pass just 36 million miles from our star, receiving as much radiation as Mercury typically does. And given that daytime temperatures on Mercury reach 800°F, we can assume the comet’s nucleus will heat up to several hundred degrees. So, what will happen to it under such extreme conditions?

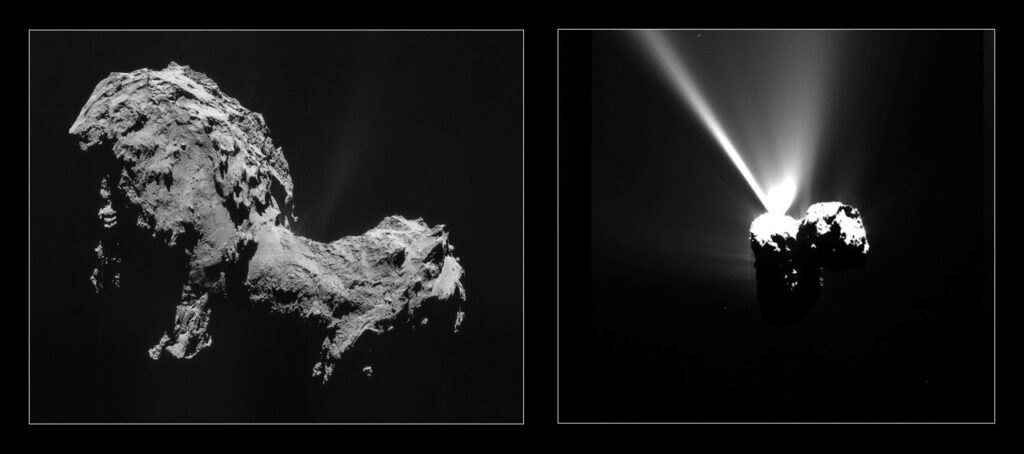

In the 1950s, American astronomer Fred Lawrence Whipple proposed a model for the comet nucleus, now known as “dirty snowball.” This model describes a mixture of rock, dust, ice, and frozen gases, primarily carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2). In the outer regions of the Solar System, where temperatures are close to absolute zero, the gases in the comet’s nucleus remain solid. However, as the comet approaches the Sun, the nucleus undergoes a process called sublimation, transitioning directly from solid to gas. The water vapor and gas mixture then carry dust particles away from the nucleus, forming a long, spectacular tail.

Whereas Whipple’s proposed model was just a hypothesis at the time, space missions that studied comets have since provided direct confirmation and photos of this process in action. For example, the Rosetta mission followed the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for over 2 years (from August 2014 to September 2016), including its perihelion approach in 2015. In the images below, we can see the change in the comet’s appearance during its aphelion (the farthest point from the Sun) and perihelion (the closest point to the Sun). In the latter case, we can observe powerful gas jets breaking through the thick, rocky crust.

Like all comets, C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) orbits the Sun according to Kepler’s laws. This means its speed will be at its highest during perihelion, which is something to keep in mind when planning to spot the comet, whether you’re doing it visually or taking photographs. After just 10 to 15 minutes of observation, you might notice a slight shift against the starry background, and by comparing the position of this ghostly cloud in the sky over several days, you’ll see just how much it changes.

New observations and forecasts

During perihelion, the comet brightens significantly as gas and dust from its nucleus are released at peak intensity. The front row seats for this event have been claimed by residents of the Southern Hemisphere, along with astronauts, of course. A few days ago, we shared stunning footage of the comet rising above Earth, captured by the ISS commander Matthew Dominick. Tonight, he shared a new time-lapse that shows just how much the comet’s brightness has increased.

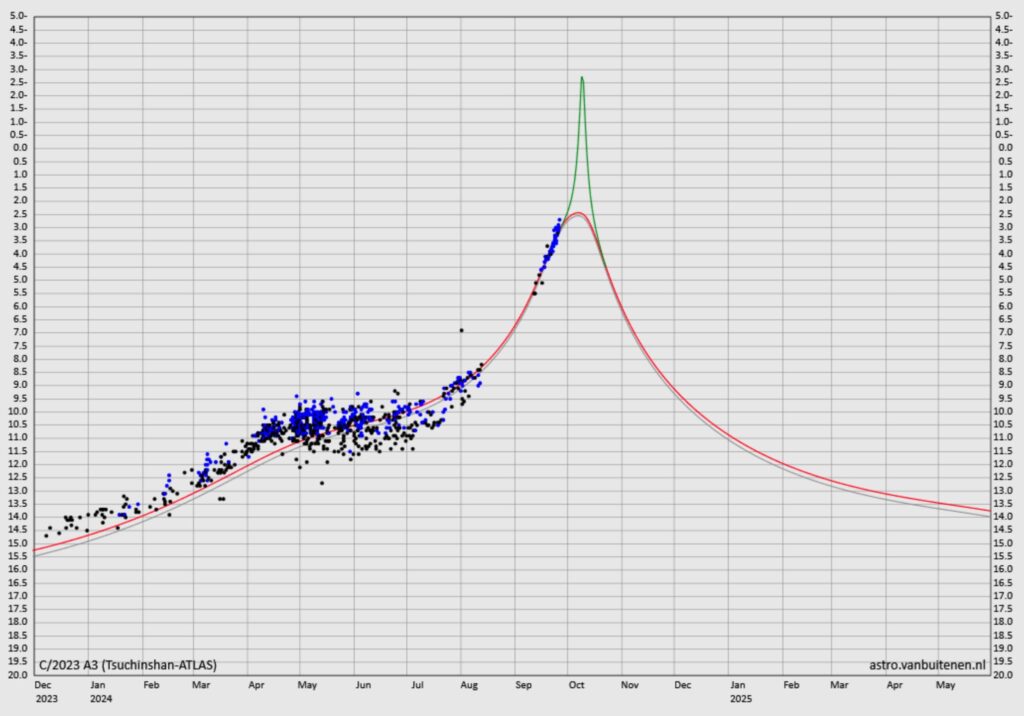

Observers on Earth are also noticing the increase in the comet’s brightness, with recent estimates slightly exceeding predictions. Since September 23, reports from both amateur and professional astronomers have been pouring in — all noting sightings with the naked eye. By September 26, some brightness estimates had reached 3.0 – 2.6m (the lower the value, the brighter the object). Updated data suggests that even with the most pessimistic forecast, the comet will likely shine at around 2.5-2.4m in the first days of October, placing it just below the bright stars of the Big Dipper in terms of magnitude. On the graph below, the more optimistic green peak reflects the effect of direct scattering on the dust particles in the tail. If these predictions hold true, the comet could shine two to three times brighter in early October.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the conditions for observing the comet are currently much better than in the Northern Hemisphere. This is due to the orientation of its orbit: near perihelion, the comet dives below the ecliptic plane. Just a few days ago in our latitudes, the comet was rising with the Sun, making it impossible to catch a glimpse of it, whether visually or photographically. In contrast, in the Southern Hemisphere, the comet was significantly ahead of the Sun, allowing many observers in Australia and the Philippines to capture stunning landscape photos that showcase the beauty of its tail.

But as the position of C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) gradually changes, we will finally get a chance to see it. On September 25, renowned Czech astrophotographer Petr Horelek captured the comet from 50° north latitude. That same morning, Andrii Nikolenko from Odesa spotted the comet hanging incredibly low over the sea horizon, blending into the pre-dawn mist. It was nearly impossible to capture the comet distinctly in a single frame, but with some skilled post-processing, a faint dot was eventually revealed, confirming the first observation of C/2023 A3 in Ukraine. The very next day, Satoru Murata shared his image taken from New Mexico. Both Petr Horelek and Satoru Murata conducted their observations in the mountains, which provided them with a visibility advantage over those observing from the sea.

How to catch the comet in perihelion: keep an eye on the waning Moon

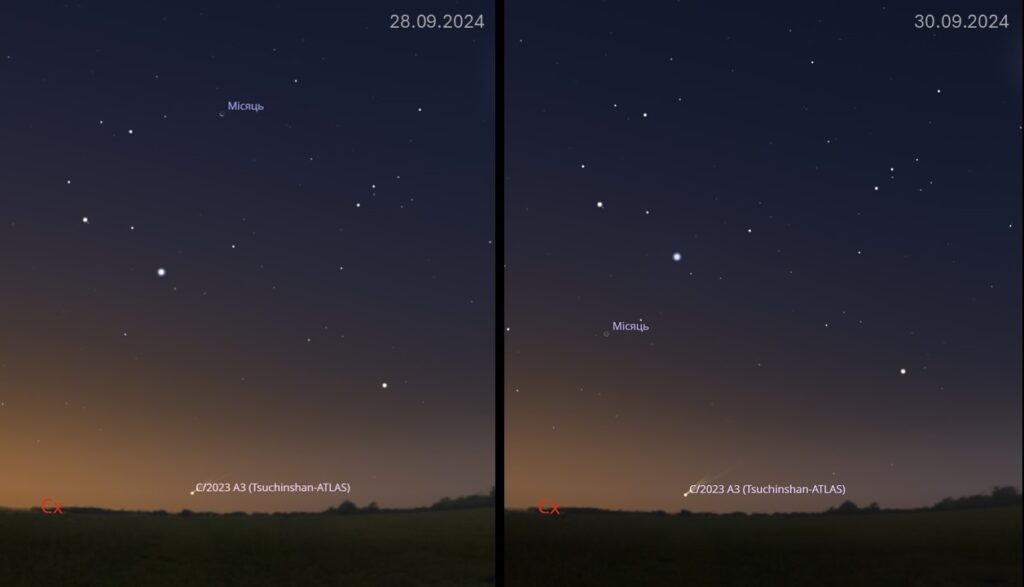

Over the next few days, roughly from September 28 to October 2-3, the Northern Hemisphere will have the best chance to observe the comet near its perihelion. Let’s be honest, though — spotting the comet will still be quite a challenge in our latitudes, making the search feel akin to a hunt for a rare breed.

For comets with similar brightness, the ideal conditions occur when the Sun is no higher than 10° below the horizon. As it stands, we expect that even at -8°, you might still be able to capture the comet with a camera or an amateur telescope, but it’s unlikely to be visible to the naked eye. These conditions will happen around 12 AM EDT in the United States and 5 AM CEST in Europe. However, it’s a good idea to check digital planetariums for conditions in your specific area. The window for morning observations will be quite narrow—only about 15 to 20 minutes—so don’t miss your chance! Despite the comet’s predicted brightness, it will quickly fade into the pre-dawn glow.

In this astronomical hunt, we’ll have an unexpected ally — the Moon. On October 2, there will be a new moon, so its brightness in the days leading up to the comet’s approach won’t be an issue. In fact, from October 28 to 30, the thin crescent of the old Moon could actually help you spot the comet, as their paths will align closely. Just aim your camera, telescope, or binoculars at the right spot on the horizon beneath the Moon, and you might catch a glimpse of the comet. Since the comet will be extremely low in the sky, choose a viewing spot with an unobstructed horizon, and the higher ground you can find, the better.

From around October 4 to 11, the comet will be off-limits for observations since it will be passing almost directly between us and the Sun. On the bright side, this could actually make its emergence more stunning due to the direct scattering effect, potentially boosting the comet’s brightness by about a hundred. Its proximity to the Sun might also make it visible enough to photograph for solar space telescopes like SOHO. However, the unpredictable nature of comets makes it tough to give any definitive forecast. Still, if C/2023 A3 shines as brightly as Jupiter, you might catch a glimpse of it on the night of October 8-9 in the U.S. or just before sunrise in Europe.

Flying past Earth

Though C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) is expected to reach its peak brightness near perihelion, the distance from Earth also plays a crucial role. As the comet moves away from the Sun, it will start approaching us, hitting its closest point to Earth on October 12 at about 44 million miles, finally granting us our star moment. After that, visibility in the Northern Hemisphere will improve as the comet will set after the Sun, allowing for later observations each day. However, there’s a catch: as the comet drifts away from the inner Solar System, it will gradually start to fade.

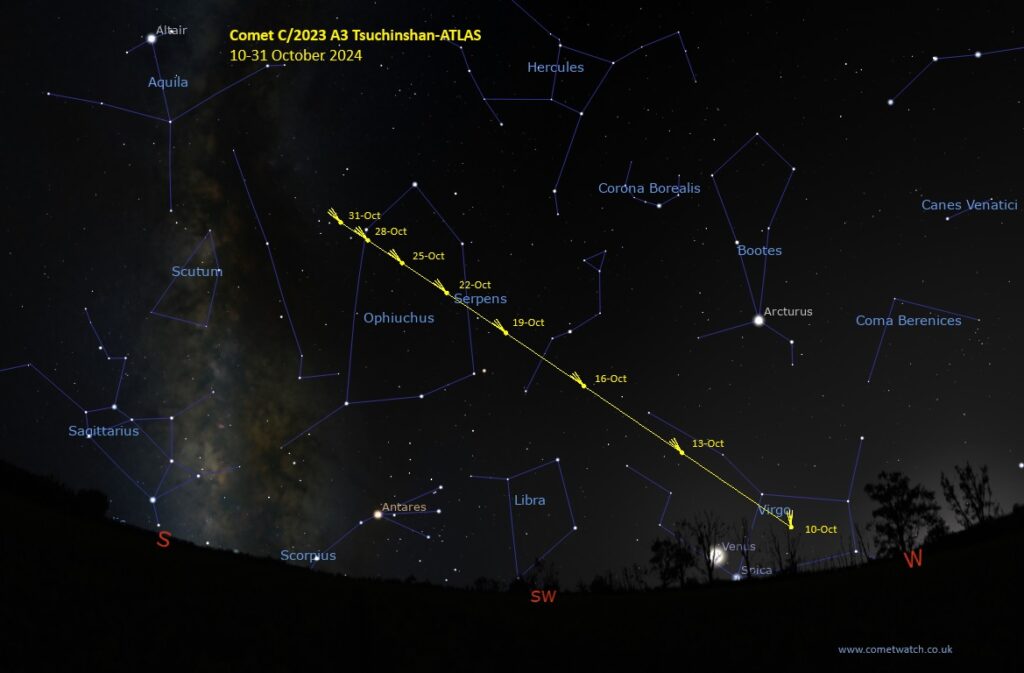

Current estimates suggest that the best days for observing the comet will be from October 13 to 15, around 11:50 AM to 12:00 PM EDT in the United States or 7:50 PM to 8:00 PM CEST. This time, you’ll want to find a viewing spot with a clear westward view. The comet might even be visible to the naked eye during this period. For binocular observations, it should remain visible until the end of the month. The only downside will be the increasing brightness of the Moon.

Apart from October 12, another key date for observation will be October 14, when the comet crosses Earth’s orbit. During this time, you might even catch a glimpse of an anti-tail — a thin spike extending in the opposite direction of the main tail. This unusual phenomenon is caused by the heavier particles in the comet’s nucleus dispersing along its orbit and trailing behind it.

While C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) may well earn the title of Comet of the Year, we don’t expect it to shine as brightly as C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) did four years ago. That said, comets visible to the naked eye are a rare treat, so we definitely encourage you to get out there and take a look. Wishing you clear skies!