For astronomical observations, where you conduct them on Earth plays a huge role. Good observational conditions require arid highland climate with clear skies and low atmospheric turbulence. This significantly narrows down the list of suitable locations, most of which already host sizable observatories. Soon, these facilities will also be joined by new large telescopes.

Why Astronomers Find the Atmosphere Uncooperative

It’s fair to say Earth’s atmosphere and astronomers aren’t the best of friends. The planet’s protective layer only appears transparent, but in reality it interferes with a wide range of electromagnetic waves, often distorting them. As a result, the largest telescopes are less accurate than we’d prefer them to be. For more precise readings, it’s more effective to build observatories in space or celestial bodies devoid of atmosphere, like the Moon, for instance.

Unfortunately, the largest telescopes we have are also extremely heavy, with their mass exceeding hundreds of tons, which makes launching them to the Moon or into near orbital space very difficult. As a compromise, scientists have to find the best places on Earth to house these giants.

First and foremost, a good place for an observatory must be remote to minimize light and industrial pollution in metropolitan areas. Secondly, telescopes should be located at high altitudes where the atmosphere is thinner and the air clearer. And so, the mountains.

The third requirement concerns the sky in the observatory’s location. It must remain relatively cloudless throughout the year, as cloudy conditions make observation impossible. And the fourth and last issue is the atmospheric turbulence. In highland locations, it must remain relatively low to minimize image distortion caused by air currents.

Places that can fit all of these requirements are usually located on volcanic islands in the Pacific or on highland mountainous deserts and plateaus. Hence, why the largest Ukrainian telescopes are located in occupied Crimea that has the best spots for studying stars and galaxies.

Of course, our planet has other, more suitable places for this task. And if you look at the locations of existing and future large telescopes, a clear pattern starts to emerge.

The Canary Islands

The Canaries, a Spanish archipelago off the northwestern African coast, are mostly known as a global tourist trap, but their other claim to fame is that of one of the main astronomical hubs.

It is here on the island of La Palma that we find the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, located at the top of the mountain of the same name and rising to 2.4 kilometers, or roughly 1.5 miles, above sea level. The climate of the Canaries is dry enough, with annual sunlight clocking at over 3,000 hours. And whatever cloudy conditions the islands do get, none of it can reach high enough to obscure the telescopes’ view.

The Roque de los Muchachos observatory is equipped with a wide range of astronomical instruments, which it started acquiring in the mid-20th century, and can boast telescopes with mirrors spanning between 1 and 4.2 meters — or 3.3 and 13.8 feet — in diameter. But its main observational instrument, the Great Canary Telescope, was actually built in 2007.

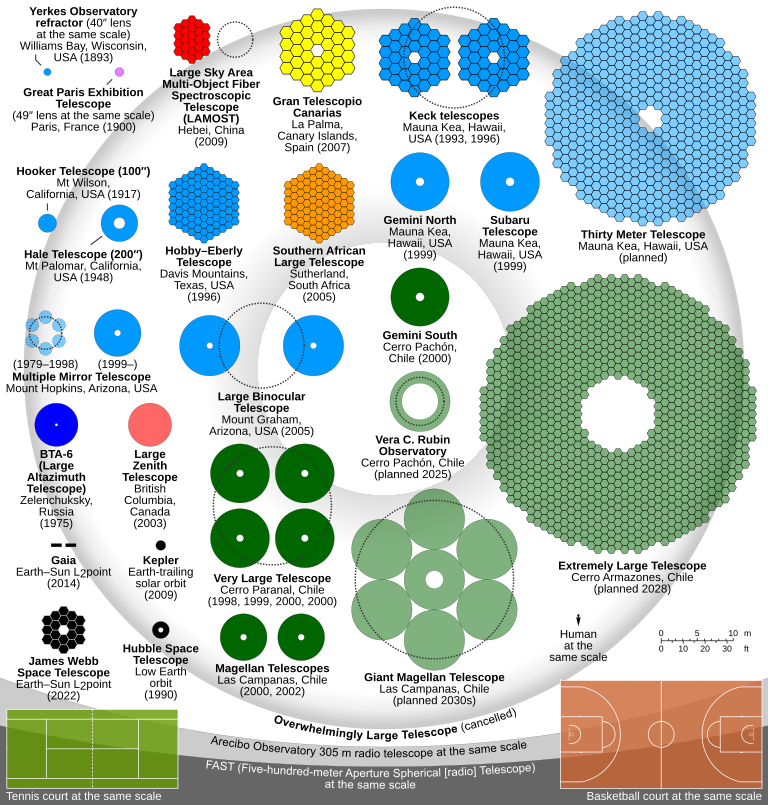

It’s a reflector whose mirror spans 10.4 meters, or about 34 feet, in diameter. Comprising 36 separate hexagonal segments, this is the largest telescope on Earth. Able to detect objects a billion times fainter than what the human eye can perceive, this telescope can also break the observed matter down into a spectrum. While the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona is larger in terms of total mirror surface, each of its two mirrors has a smaller diameter than the one at the Great Canary.

The Roque de los Muchachos Observatory is run by the Canary Institute of Astrophysics, located on the neighboring island of Tenerife, and together they form the European Northern Observatory. Though at the moment the island has no plans for constructing more observational instruments, nobody rules out the possibility of building even larger telescopes there.

Hawaii

Another popular location for both tourists and astronomers is Hawaii. Located in the middle of the Pacific, this 50th American state is not the most ideal of options for sky observations.

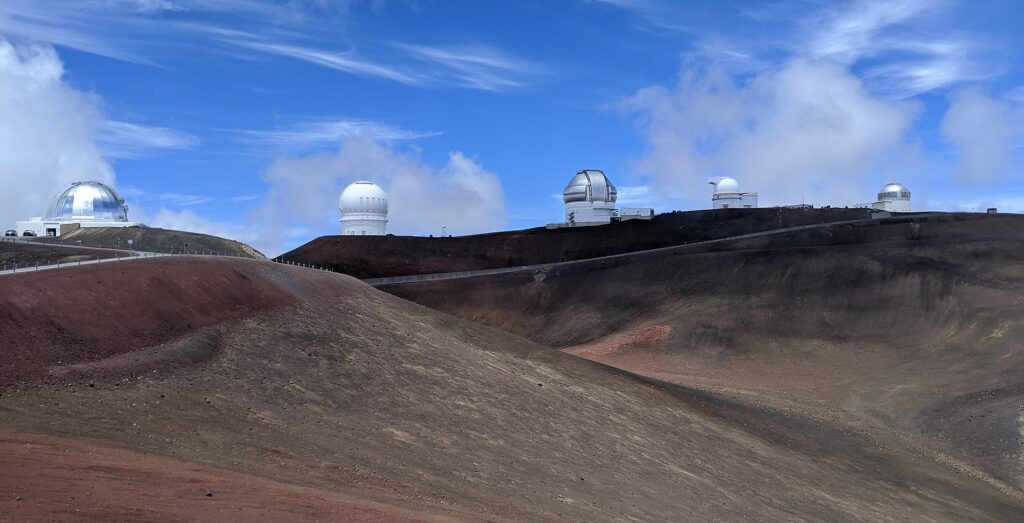

Hawaii is a tropical island archipelago that receives high amounts of annual precipitation. However, the majority of its rain clouds accumulate below the Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanoes that rise over 4,000 meters, or 13,800 feet, above sea level. At their peaks, the sky remains cloudless, and the air is clear.

In the 1960s, these favorable conditions at the summits led to the construction of large telescopes above the 3,505-meter (11,500 ft) mark, amounting to 13 telescopes in total over 60 years of development. Until recently, that whole area has been home to astronomers and their telescopes, some of which operate in other light spectrums, namely infrared and submillimeter ranges.

The observatory’s largest instrument, located on Mauna Kea, is in fact two telescopes — Keck I and Keck II — whose construction was completed in the late 1990s. Each of their mirrors spans 10 meters (ca. 33 feet), which made them the most powerful telescopes on the planet until the launch of the Big Canary Telescope in 2007.

The twin Keck telescopes were the first to use adaptive optics systems, making it possible to work around the atmospheric interference, which was already low to begin with. This opened the doors to many new discoveries. Most notably, in 1999, scientists used observations conducted with those telescopes to come to a groundbreaking conclusion: the invisible object at the center of the Sagittarius A* galaxy was, in fact, a supermassive black hole.

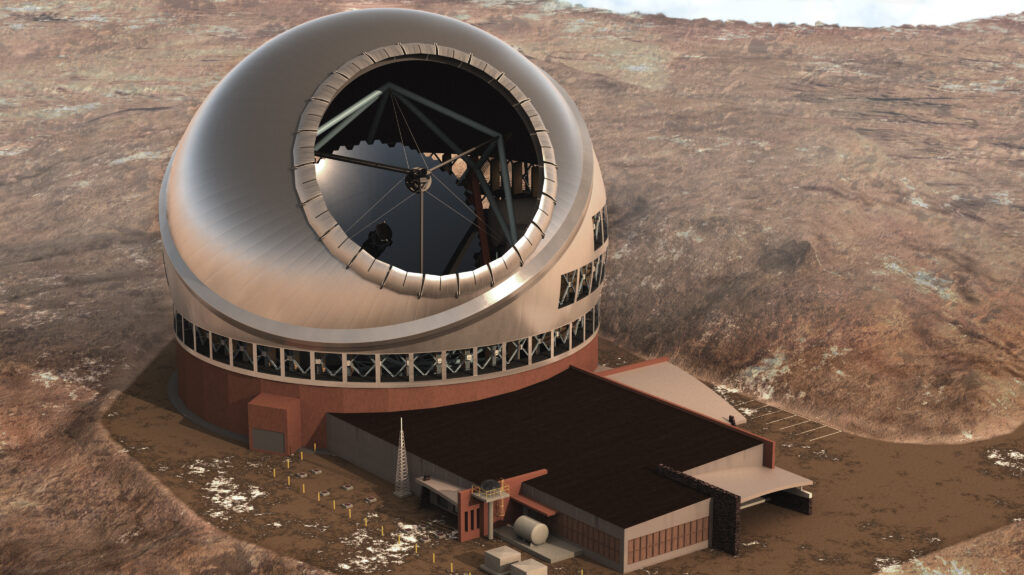

Manua Kea will also host a new, even larger instrument — the Thirty Meter Telescope, named so for the actual size of its mirror, which will comprise 492 separate segments. The construction began in 2014 and should be completed by the mid-2020s, with the first scientific research commencing in 2027.

But Manua Kea, with its unique flora and fauna, doesn’t belong to astronomers. It’s also a sacred site for the Native Hawaiians and holds great significance in their cultural heritage. In 2016, the construction of the new telescope was halted due to disputes with the Native activists.

In 2022, a semblance of a peaceful resolution was finally achieved between the parties. According to the agreement, the Thirty Meter Telescope project will be allowed to proceed on the condition that the existing telescopes will be disassembled. So it appears that Hawaii won’t be on the list of possible locations for future observatories.

The Atacama Desert

Another possible location for observations, the Atacama Desert in Chile, is not the most appealing tourist destination. With its sufficient elevation above sea level, this South American desert is known as the driest place on Earth, receiving only tiny amounts of precipitation per annum. Naturally, this creates extremely harsh living conditions.

The extreme conditions that shape Atacama and its surrounding mountains are also what make it so suitable for astronomical observations. Additionally, the cohabitation of scientists and the native population is less problematic. All of this has formed the desert we see today — a barren landscape inhabited by astronomical observatories.

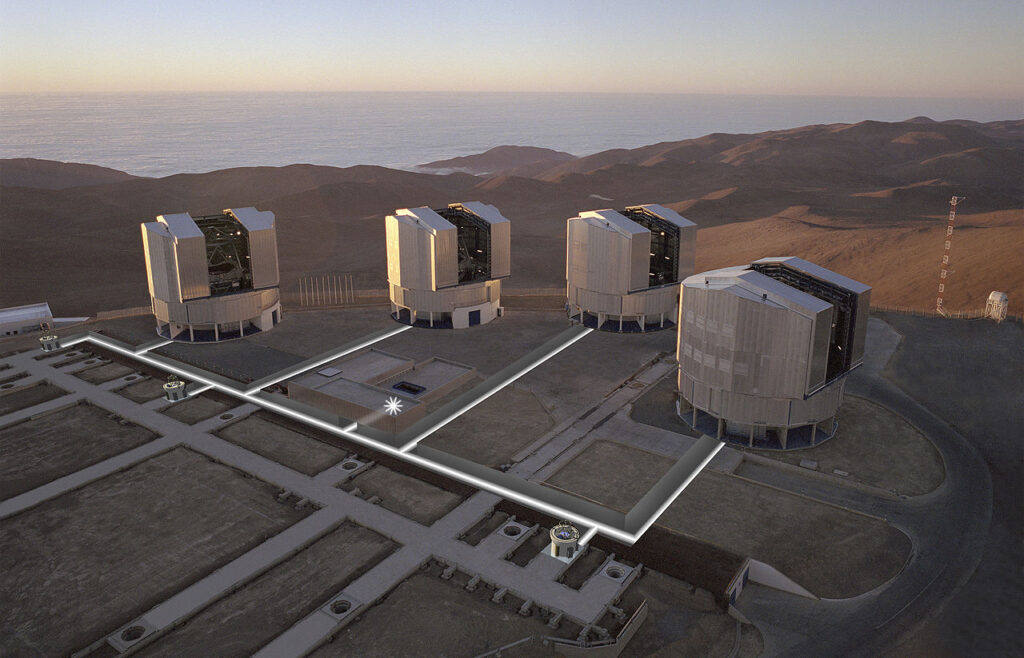

Three of them form the joint European Southern Observatory. The first facility, located on the Cerro Paranal summit at the height of 2,635 meters or 8,645 feet, is the one in possession of the famous VLT, or the Very Large Telescope. Despite the name, this telescope is actually made up of four separate reflectors — each with a mirror spanning 8.2 meters (26.9 ft) in diameter — that operate as a single unit. It’s currently the world’s most powerful optical ranging system.

In 2014, construction of another project, the Extremely Large Telescope or ELT, commenced on Cerro Armazones, a mountain adjacent to Cerro Paranal. The ELT’s mirror will comprise 798 segments and span 39.3 meters (39 feet) in diameter. This design increases the reflector’s light sensitivity by about 15 times compared to all currently active telescopes.

The second European observatory in the Atacama is La Silla, located at the summit of the same name at 2,400 meters or 7,874 feet. Unlike Paranal, this mountain is practically brimming with telescopes, though all of them are relatively minute, with the largest mirror measuring only 3.6 meters or 12 feet.

Llano de Chajnantor, the third European observatory, works only with radio telescopes. In general, the mountains of Atacama are host to a wide range of astronomical facilities. After all, the desert’s arid land is no longer suitable for life, but it provides perfect conditions for astronomical research.

As for future projects, there are quite a few of them currently in the works. The first is the near complete Vera C. Rubin Observatory located on Cerro Pachón which will soon be ready to open its doors for research.

Though its telescope mirror measures only 8 meters (26 feet), the field of view will be extremely wide — 9.6 square degrees — allowing scientists to search for dark matter, dark energy, near-Earth asteroids and Kuiper belt objects.

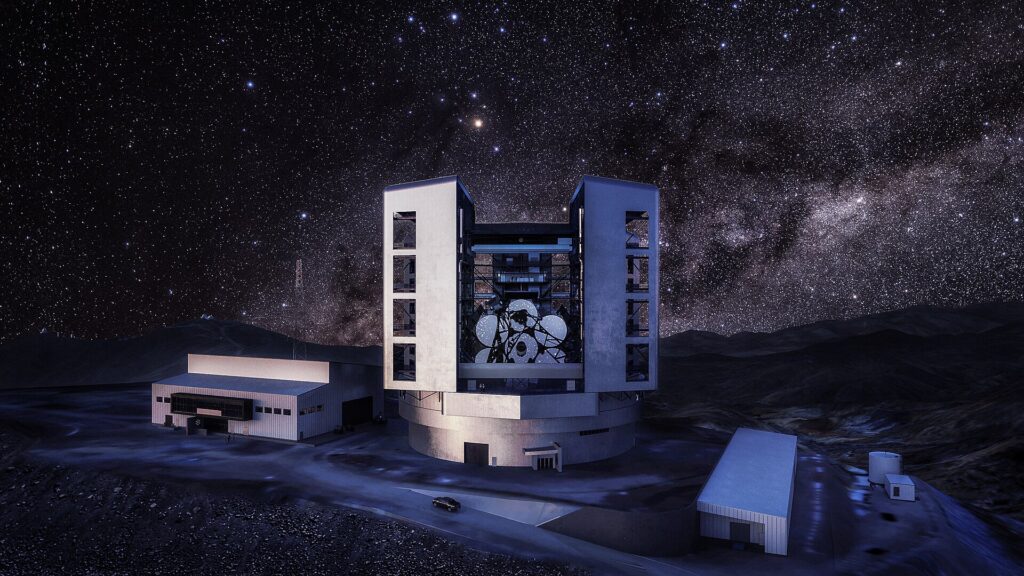

The second major project set to commence in the Atacama Desert is the Giant Magellan Telescope. This structure will have a mirror spanning 24.5 meters, or roughly 80 feet, itself consisting of eight circular segments, each measuring 8 meters or 26 feet in diameter. The GMT is expected to be completed by 2029.

All things considered, we can safely predict that any future project for a larger optical telescope will likely find its home in the mountains of the Atacama Desert.

Other Places for Observation

Although the three aforementioned options are the best possible locations for large astronomical instruments on Earth, there are other alternatives that could also work fairly well. The mountain ranges in western United States look very promising. Their terrain is very reminiscent of landscapes we are so used to seeing in old Hollywood westerns. The climate here is also quite dry, but it does get cloudy more often, and the turbulence is noticeably higher.

The Large Binocular Telescope, or LBT, is located on Mount Graham in Arizona and consists of two instruments, each with a mirror measuring 8.4 meters or 28 feet. When the two telescopes operate in tandem, they form one large telescope with a single ‘virtual’ mirror that measures 11.9 meters (39 feet) in total.

Another interesting option for large telescopes is the Karoo semi-desert in South Africa. While the region is unlikely to make any lists of top beach destinations to get some tan, more adventurous travelers might find plenty of exciting things to occupy themselves with.

The region’s dry climate lays perfect ground for astronomical observation, and has already welcomed one such facility into its arms — the South African Large Telescope, or SALT, which also boasts a 10-meter (33-foot) mirror. Though there are no other projects currently planned, it’s very likely that future telescopes might find their new home in Karoo.

When it comes to astronomical opportunities, Australia had no such luck in this area. And it does seem strange — after all, the continent is largely made up of desert, making it a perfect candidate for astronomical research. Unfortunately, the Australian desert is not elevated enough, clearing only a few dozen feet above sea level. This is why its largest instrument, the Anglo-Australian Telescope on Mount Woorat, also known as Siding Spring Mountain, measures only 4 meters or 13 feet.

The Himalayas, on the other hand, seem like a good place for astronomical observatories. But that’s only theory. In reality, the conditions here are humid, and the climate is unpredictably rough, so it would be extremely difficult to get any consistent observations of the sky. India’s Himalayan Chandra Telescope (HCT) at the Hanle Observatory, rises to 4,500 meters (14,764 feet) above sea level, making it one of the highest observatories in the world, but its infrared telescope is rather small, measuring only 2 meters or 7 feet in diameter.

As for China, their astronomical scope remains largely obscure. The country’s main observatory at the Xinglong Station is equipped with a 4-meter (13-foot) LAMOST, or the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope, located in the Yan Mountains at about 960 meters (3,150 feet) above sea level. Though this mountain peak offers some stunning views, it’s less than perfect for actual observations.

Tibet, on the other hand, has all the right conditions for observations, including the high altitude and fairly dry climate. Chinese astronomers have been eyeing this region for a long time. Though current plans only foresee the constriction of a small 2.4-meter telescope, there’s also been some talk of adding a 12-meter instrument. One thing can be said for certain — if any region can challenge Atacama for its title of the “realm of astronomers”, it will be Tibet.

The last potential place on the list is also one with the most extreme conditions on Earth — Antarctica. More specifically, the suggested locaton is smack-dab in the middle of the continent’s ice plateau. Though this area is technically just pure glacier, the sky above it is both calm and crystal clear.

That said, building a large observatory in Antarctica would be extremely difficult, even for experts that are used to work in harsh conditions. The proposed site is also fairy close to the location with the lowest ever recorded temperature on Earth. There, it can drop as las as -75 °C or -141 °F.

Most regions with top tier conditions for astronomical observations are also some of the least vacation-friendly places on the planet. Instead, they can offer something more adventurous, providing a truly unmatched life experience with incredible astronomical opportunities at its very center.